New Exhibition Featuring Picasso, O’Keeffe, Hopper and Many Others Brings Modernism Into Focus

The artistic risk and adventure of 20th-century modernism is explored at the Smithsonian American Art Museum

All the remarks had been made, and the thank yous delivered at the recent opening reception for the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s new exhibition “Crosscurrents: Modern Art from the Sam Rose and Julie Walters Collection.” Then Rose and Walters indicated they had one final thing to announce: They were gifting David Smith’s 1952, Agricola IV to the museum.

Virginia Mecklenburg, the museum’s chief curator who had been seeking a key Smith work for the collection for 25 years, was speechless. “When they come up for sale, they’re priced way beyond the museum’s ability to acquire them,” she said of Smith’s works. The announcement further surprised her, since the collectors had just purchased the sculpture at auction last spring.

“They hadn’t even owned it maybe six months,” Mecklenburg said.

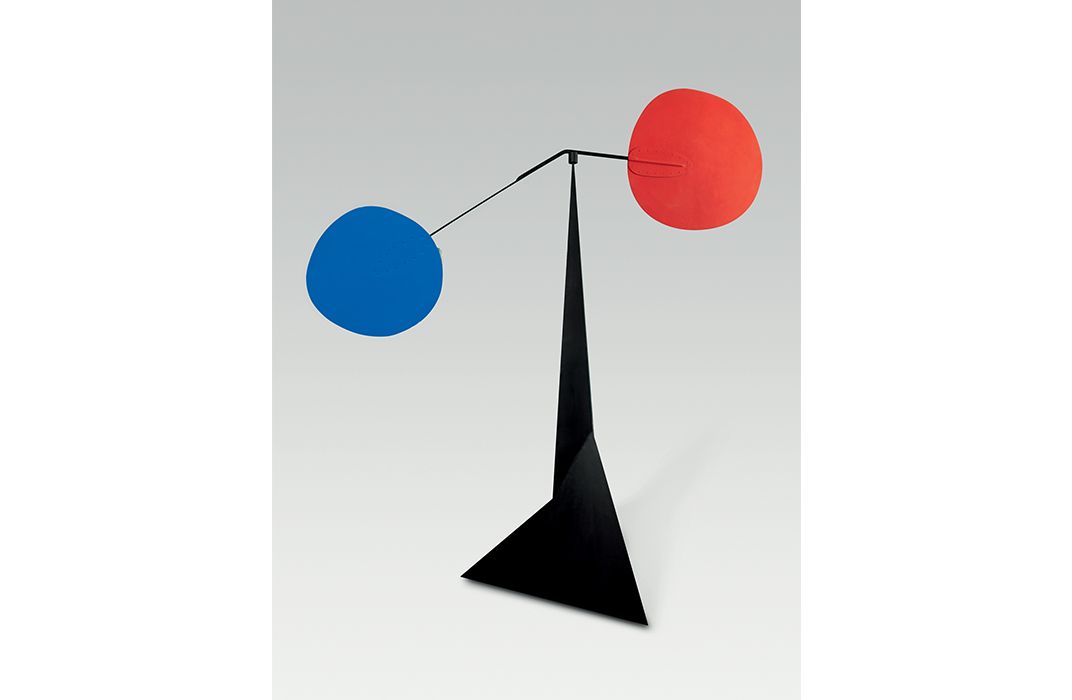

The museum’s first major Smith sculpture appears in the last gallery of “Crosscurrents,” an exhibition of 88 works by 33 artists on view through April 10, 2016. The show, which focuses on 20th-century paintings and sculptures, traces the inception and development of Modernism as part of an exchange of ideas between European and American artists.

The museum has acquired several other works by Smith over the years, including the small 1956-57 bronze, Europa and Calf, the 1938-39 study, Private Law and Order Leagues, and the 1935, Reclining Figure, a sculpture which also appears in the show.

The latter, said Mecklenburg, acquired in 2013, is one of Smith's earliest works, “when he was just beginning to weld things together.”

Smith was born in 1906 in Decatur, Indiana, and he worked as an automobile riveter and welder before moving to New York, where he study at the Art Students League. In 1957, the Museum of Modern Art did a retrospective of his work. His life was cut short when he died from injuries he suffered in a car crash in 1965; the next day’s New York Times obituary called the 59-year-old “an important innovator in contemporary American sculpture and a pioneer in welded iron and steel constructions.”

One such construction, the Agricola series of 17 works—from which the new promised gift comes—is titled for the Latin word for “farmer.” The project was Smith’s first major series, in which he welded together abandoned machine parts from a farm near his studio in Bolton Landing, New York.

The flowing contours of Agricola IV are so calligraphic that they evoke the graphic pictoral lines of Xu Bing’s 2001, Monkeys Grasp for the Moon, displayed at the Smithsonian's Sackler Gallery of Art. “From every angle it becomes something slightly different, and very special,” Mecklenburg says of the Smith sculpture. The museum calls it “a totem from the agrarian past,” which serves as an “emblem of a way of life mostly abandoned in the industrial age.”

Another piece in the show that partially serves as a time capsule is an early 1925 watercolor of Edward Hopper, House in Italian Quarter, which makes a return visit to the museum. (Previously it appeared in the 1999-2000 exhibition, “Edward Hopper: The Watercolors,” before it was purchased by Rose and Walters.)

“I was thrilled when I knew that they bought it, because then I’d know where it was in the future,” Mecklenburg says.

The painting—for which the artist used a variety of techniques from wet-on-wet to dry brush application (all with exposed pencil lines) to depict a loosely, yet naturalistically rendered house—is considered to be Hopper’s “first real foray” into watercolors.

“He had been struggling along,” Mecklenburg says. “His prints were having some success, but basically he had only ever sold one single painting, and that was out of the Armory show,” referring to the 1913 International Exhibition of Modern Art, hosted at New York’s 69th Regiment Armory. It was the first major U.S. exhibition of modern art from Europe.

Painting in Gloucester, Massachusetts, that summer, Hopper spent a lot of time with fellow artist Jo Nivison, whom he would marry the following year. Old houses with longstanding histories particularly fascinated Hopper. In House in Italian Quarter, Hopper, in some ways, was “celebrating the exuberance of Mediterranean color,” says Mecklenburg.

“It was the summer that launched Hopper’s career as the major realist of the century,” she says. “There’s a sense of freedom and of coming into his own at this moment.”

Hopper’s depictions of Gloucester houses are so specific that Mecklenburg was able to pinpoint on a visit to Massachusetts exactly where he stood when he painted them. “The light posts are there. The fire hydrants are still in the same place,” she says. “If you move ten feet closer, or further, or to one side, the view was different.”

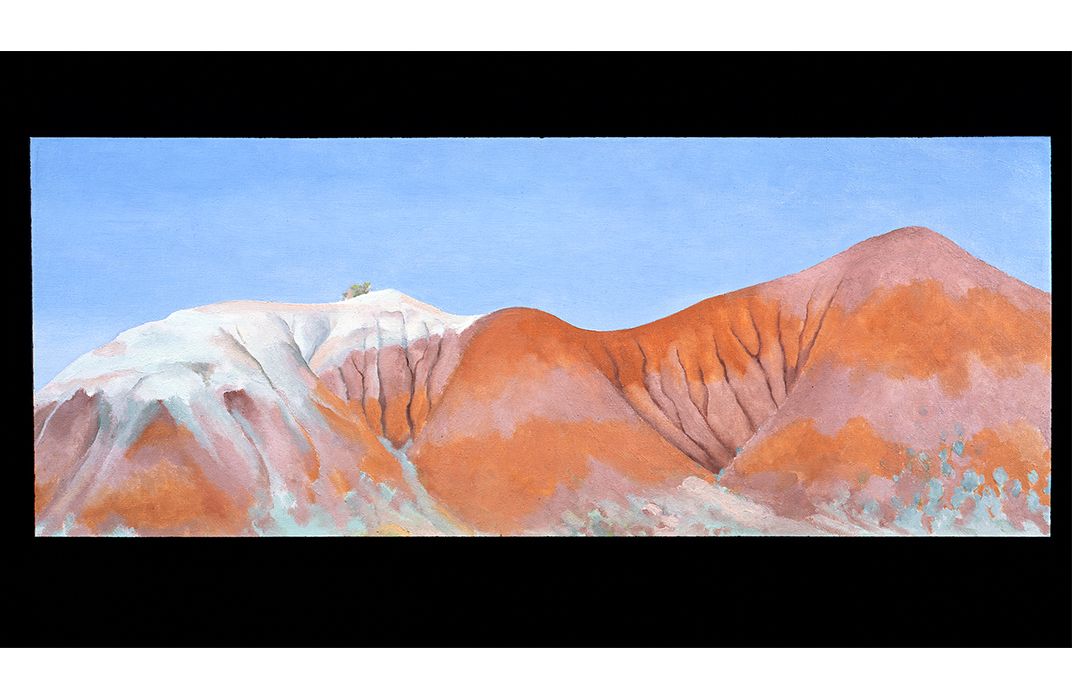

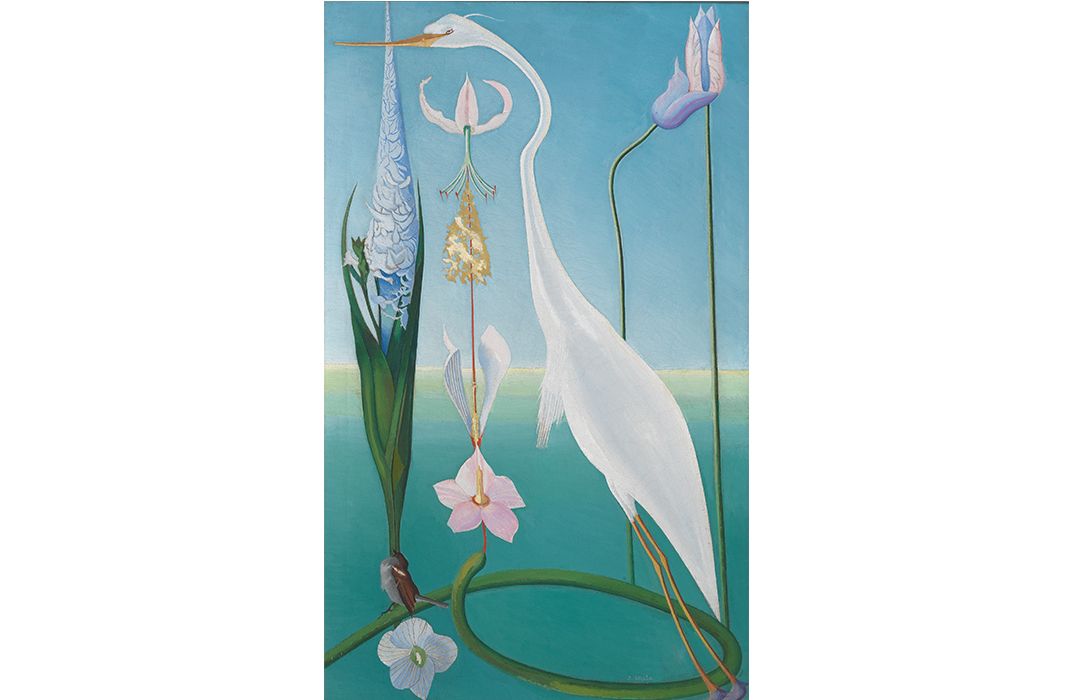

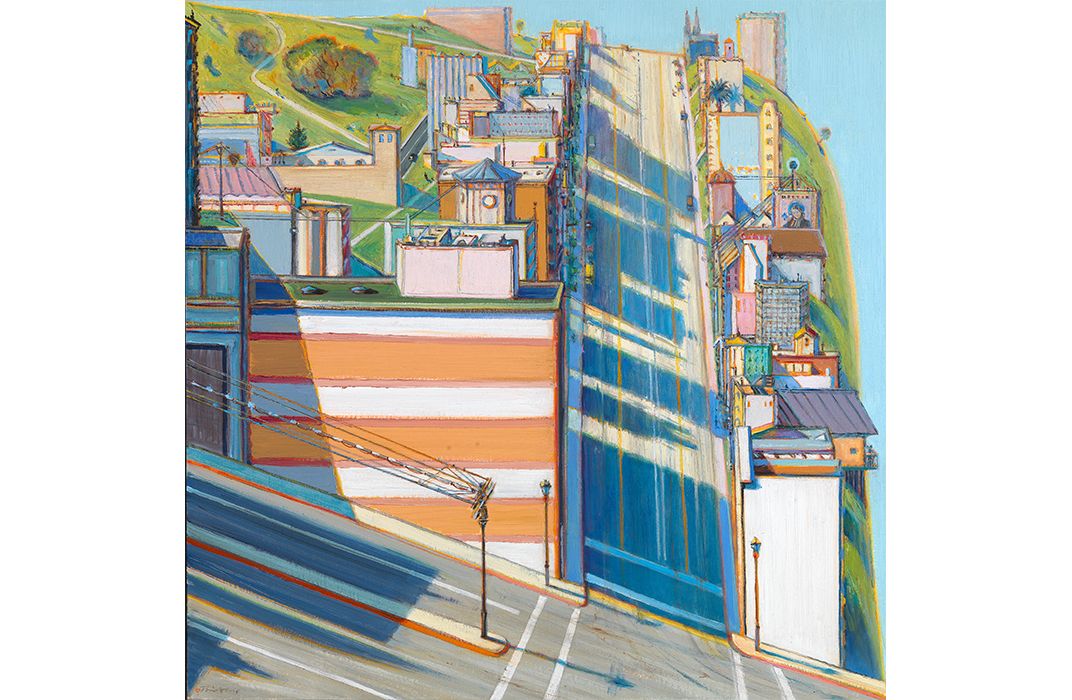

In addition to the Smith and Hopper works, the exhibition includes other promised gifts from Rose and Walters to the museum: Wayne Thiebaud’s 1998 Levee Farms and his 2001 San Francisco West Side Ridge, Alex Katz’s 1995 Black Scarf. and Georgia O’Keeffe’s 1939 Hibiscus with Plumeria.

“It’s wonderful to have that chronological range and depth,” Mecklenburg says. “We see O’Keeffe across 30-plus years of her career. There are kinships among all of them in terms of who she is as a painter, but each piece has a very different kind of personality.”

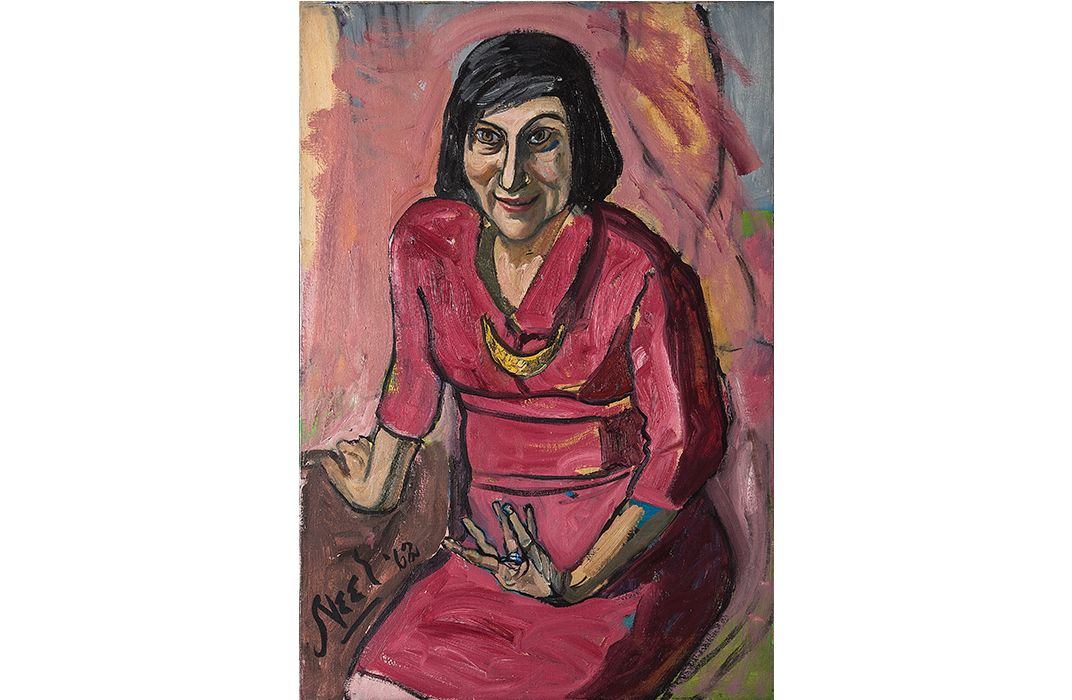

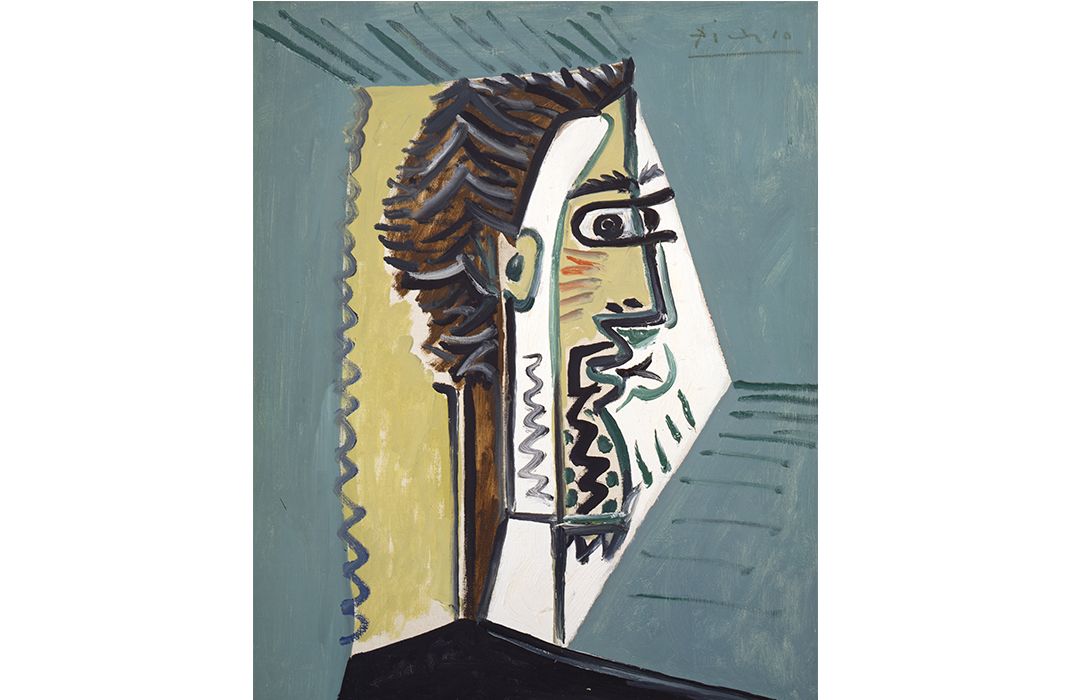

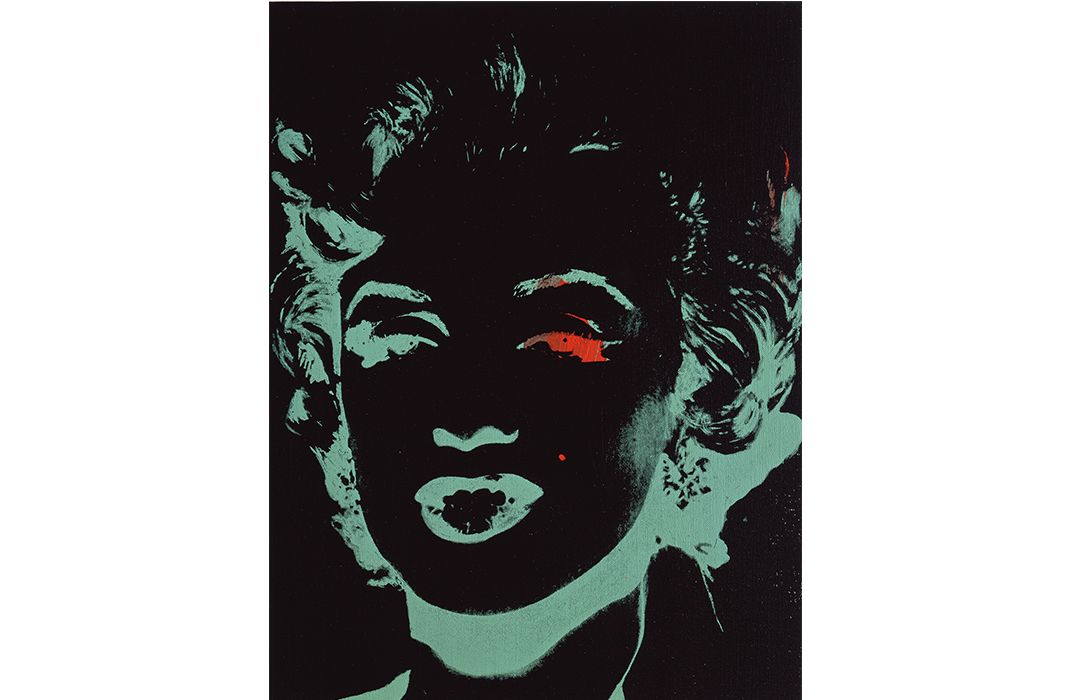

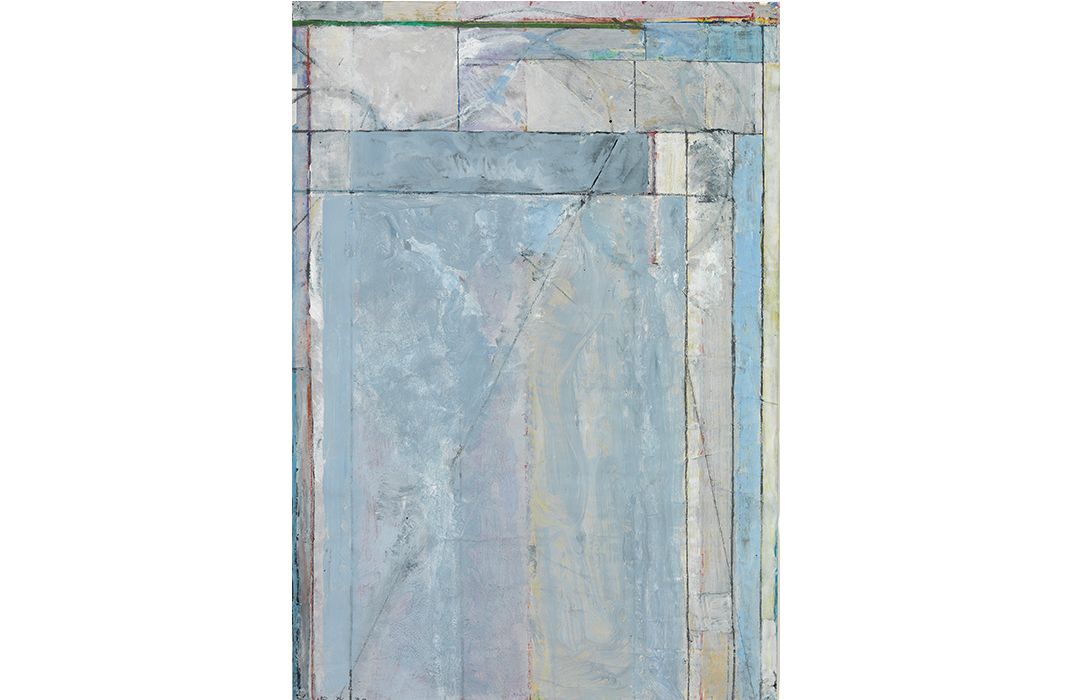

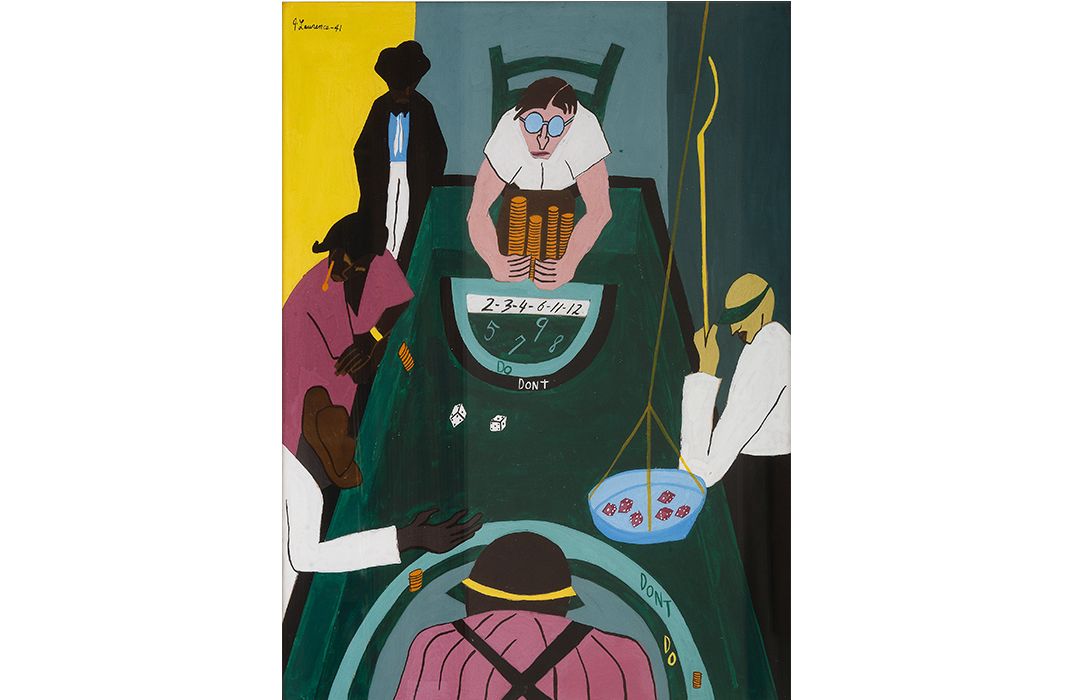

The exhibition also tells the story of other artists the duo has collected in depth, including Pablo Picasso, Alice Neel, Romare Bearden, Joseph Stella, Richard Diebenkorn, Wayne Thiebaud and Roy Lichtenstein.

“It’s not something we have the opportunity to do in a museum as often as would be nice,” Mecklenburg admits.

This kind of exhibition also presents the opportunity to tease out broad movements and meaning within this sort of body of work. Mecklenburg conceived of the exhibition almost two years ago while looking at the seven works that Rose and Walters had given the museum over the years, as well as their broader collection. She noticed a “sort of theme and thesis” emerging about what it meant to be modern in the 20th century.

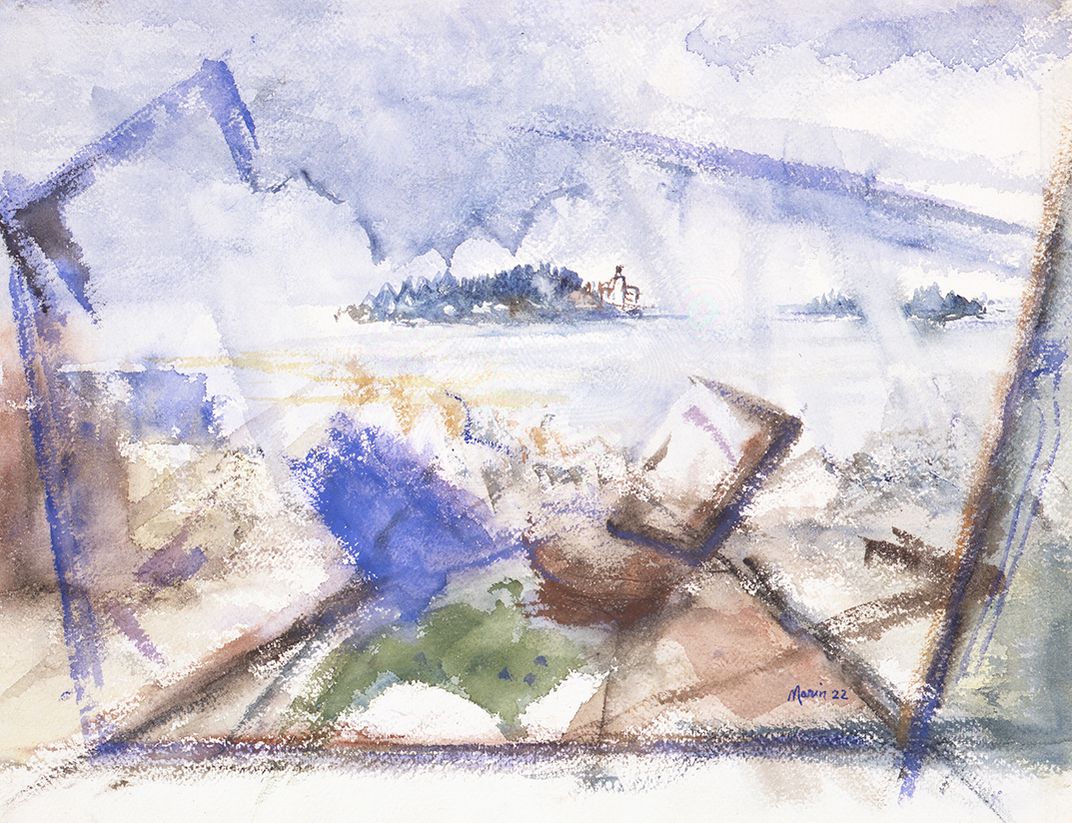

“One of the major decisions we made early on was to show not only American paintings, sculpture, works on paper, and watercolors, but to talk a little bit about the intersections,” she says. “Which is not to say that you see something in Marsden Hartley echoed in Picasso. It’s that there is this mindset that runs really from the early years of the 20th century all the way through for the people who were willing to break the rules, basically. They did not feel obliged to do what everybody had done before.”

That sense of risk-taking, of adventure, and of looking beyond was a “shared substrate”—both philosophical and aesthetic—that bound together much of what the artists were doing at the time, according to Mecklenburg.

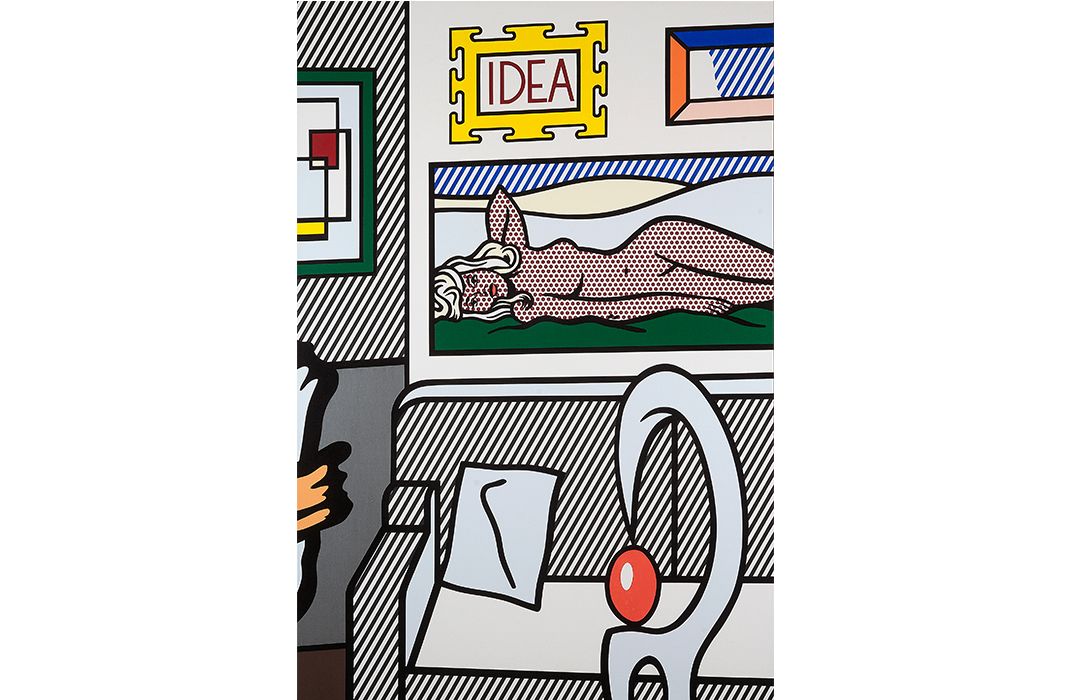

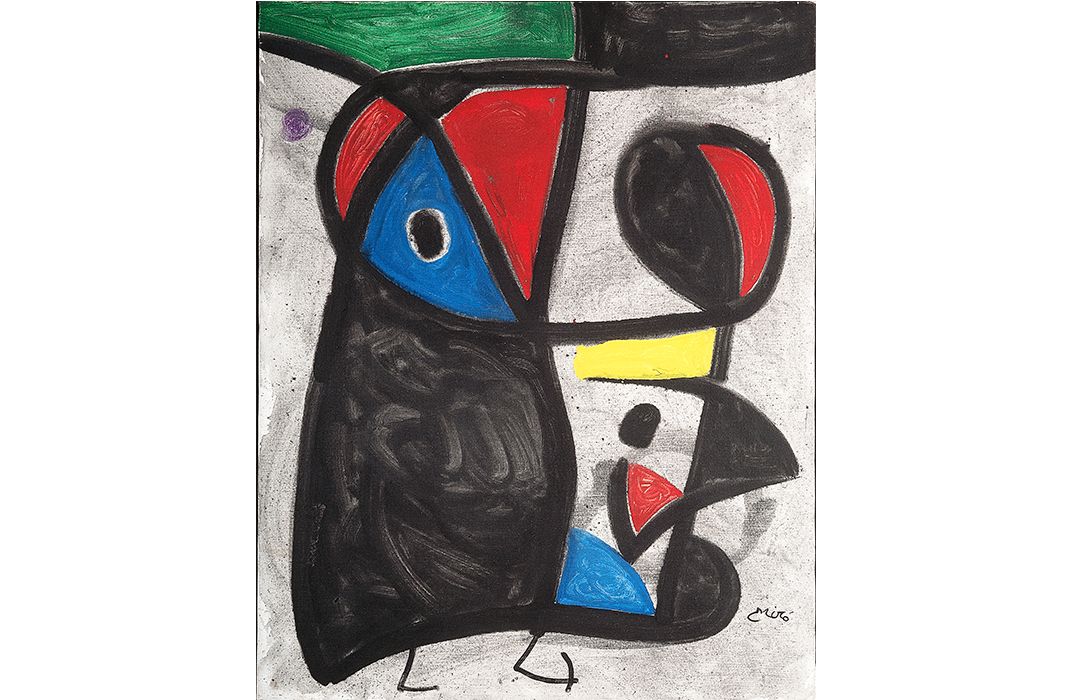

Works that reflect what artists were thinking at the time abound in the show, from Roy Lichtenstein’s 1993 Idea, which actually contains a framed work-within-a-work bearing the word “idea,” to Picasso’s ceramic works, one of which, “has the feel of an ancient frescoed wall that bears traces of layers accumulated over time,” according to the show's catalog.

The depiction of what Mecklenburg describes as a “quasi-bull fighting” scene is rendered in a manner reminiscent of the cave paintings at Altamira in Spain or Lascaux in France. “Picasso thought a lot at different moments in his life about Spain and what it meant,” she says. “There is a real sense of the archaic here. It’s a way for Picasso to both remember and claim Spain as his heritage.”

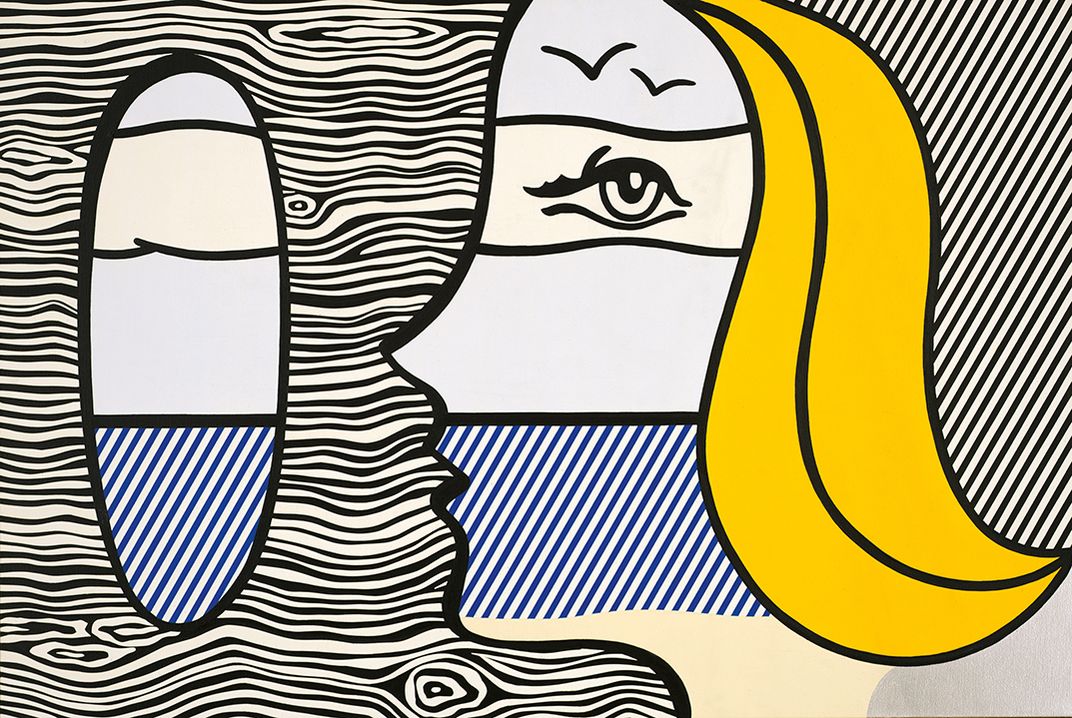

Lichtenstein’s works, including the 1977 Landscape, which evokes Rubin’s Vase—the drawing which resembles both two faces and a vase—appear in the section “double takes.” The title Landscape, Mecklenburg notes, “makes you stop and take a minute to read it. It’s not a landscape. It’s a seascape,” she says. The figure in the work who looks out a ship’s window, she notes, has eyebrows made of seagulls.

“He had a fabulous sense of humor,” Mecklenburg says of Lichtenstein.

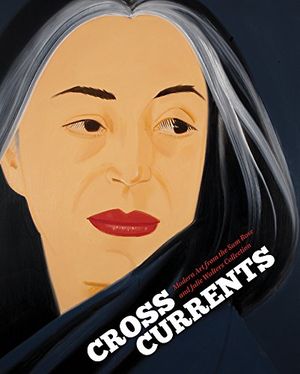

Katz’s Black Scarf, which is the first work to confront viewers when they enter the show, also has a degree of playfulness. The painting represents Katz’s wife Ada, who is “tiny,” according to Mecklenburg. “The painting is probably as large as she is in terms of height.”

“She is such a commanding presence,” she notes of Ada Katz, and the image’s limited palette, and thinly applied paint adds to that drama. “This wonderful sweep of the brush defines the whole thing.”

Not only is limiting one’s aesthetic tools to achieve maximum presence and meaning a good metaphorical microcosm for the art that is to follow in the show, but the work has the benefit of pulling visitors in right when they exit the elevator, which is why Mecklenburg selected it for the front wall. “She was the hands-down winner.”

"Crosscurrents: Modern Art from the Sam Rose and Julie Walters Collection" is on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C. through April 10, 2016.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mw_by_vicki.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/68/5a/685a3541-285a-49df-ac26-4590559508df/nadelman1web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mw_by_vicki.jpg)