New Exhibition Highlights the Monumental Milestones of African American History

Artifacts reveal the vibrant stories of everyday people, while also adding nuance to the landmark events taught in history classes

Amanda Carey Carter was a third-generation midwife in her family, who helped deliver babies in central Virginia for more than 49 years. She learned the practice from her mother who had previously learned it from hers. The women were vital resources in their communities, looked to as experts in their field. Black and white families alike relied on them to bring children into the world.

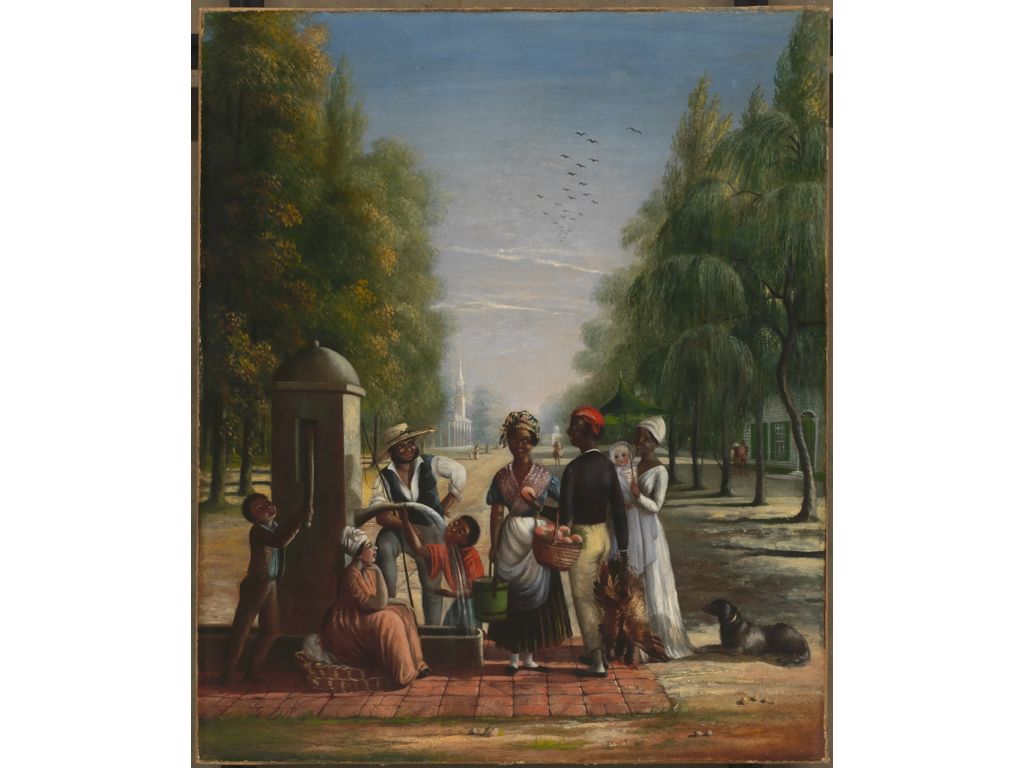

Carter’s story, and that of many others, is one often overlooked in history. A new exhibition at the National Museum of American History, Through the African American Lens: Selections from the Permanent Collection, aims to change that. The show offers a preview of the artifacts and moments chronicled in the collections of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, expected to officially open its doors in 2016.

A focus of the exhibition and the upcoming museum is not only to highlight the monumental milestones that mark African American history, but also to celebrate the everyday achievements and contributions individuals in this community have made while helping shape the United States. Says the museum's founding director Lonnie Bunch: “We want people to remember the names you knew in new ways and get to know a whole array of people who have been left out of the narrative.”

Through the African American Lens revels in the richness of this narrative. The exhibition includes formative artifacts that highlight the importance of key turning points in history including the dining room table where the NAACP Legal Defense Fund wrote the arguments for Brown vs. Board of Education, the only known surviving tent from a U.S. colored troop in the Civil War, and a shawl belonging to Harriet Tubman.

It also features intimate details about individuals and daily life including a family tree commemorating the Perkins-Dennis family, early settlers and farmers who lived in Pennsylvania and Connecticut during the 1700s. A display of vibrant, colorful hats depicts styles integral to the churchgoing experience and honors popular designers. A section made up of a brushed arbor overhang and dappled light highlights religious connections the African American community has with different faiths including Christianity, Islam and Judaism.

The many facets of the exhibition illustrate that “African American History did not start with chattel slavery,” says Curator Rhea Combs.

It’s a dynamic history that includes James Brown’s bold red jumpsuit and his infectiously exuberant music. It features the stunningly embroidered and handcrafted navy cape made by formerly enslaved designer, Lavinia Price. And it contains the dramatic black and white photos of Amanda Carey Carter, working as a midwife in homes and hospitals throughout central Virginia.

“The collections are not made by African Americans solely for African Americans,” says Bunch, “Through the African-American story, we see the American one.”

This belief is a guiding principle for the curatorial staff. However, when the museum was approved in 2003, the search for artifacts posed an initial quandary. “When we started building the museum, my concern was, could we find the artifacts of history?” says Bunch. Through partnerships with local museums and nationwide events focused on “Saving African American Treasures,” the curatorial team offered families tips for how to preserve their belongings. But many families later chose to donate those artifacts.

The outpouring of generosity—precious heirlooms from “basements, trunks and attics,” more than 33,000 artifacts—from institutions and families proved that the material culture was well intact. The team led by Chief Curator Jacquelyn Days Serwer and Combs, say that this spirit of love and community reaches deep into the soul of African American history.

Additionally, the team has created a narrative that is constantly expanding. “History looks and feels so current,” says Combs. Gesturing toward an original edition of Blues for Mr. Charlie, a play by James Baldwin that honored murdered civil rights activist Medgar Evers, she notes its ongoing, contemporary relevance as context for the discussion of social issues including protests in Ferguson and Baltimore.

“This museum has to be a place as much about today and tomorrow as yesterday,” says Bunch, “There is nothing we can’t talk about."

The National Museum of African American History, scheduled to open in 2016, is under construction on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., on a five-acre tract adjacent to the Washington Monument.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/profile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/profile.jpg)