A New Film Details the FBI’s Relentless Pursuit of Martin Luther King Jr.

Smithsonian scholar says the time is ripe to examine the man’s complexities for a more accurate and more inspirational history

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fe/a7/fea7b6ab-941a-4ef2-9bdb-16354141854f/mlk-fbi_still_1.jpg)

As the nation erupted this past year in multiple protests against systemic racism in America, the crowds often gave voice to the long-esteemed protest strategy of peace and nonviolence. The mid-century civil rights movement’s sit-ins and marches were the protest paradigm to be emulated.

The movement’s events, its leadership and its ethic of nonviolent resistance, grounded in the storied teachings of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Mahatma Gandhi, provided the pathway to the desegregation and voting rights successes of the 1960s and ’70s. Time and again, be it the summer’s protests following the death of George Floyd, or the myriad women’s marches, and many other protests on abortion, immigration, climate change, science literacy, gun control, health care and others in Washington, D.C. and across the nation, protesters hearkened to King’s lessons.

The tendency to remember the civil rights movement in this almost mythic fashion, however, stands in stark contrast to the true history of the freedom struggle as it was perceived by the nation at the time. While more than 90 percent of U.S. adults now view King favorably, a 1966 Gallup poll showed Americans were nearly twice as likely to have a negative as a positive opinion of him.

Historian Jeanne Theoharis examined the public memory of the movement in her 2018 book A More Beautiful and Terrible History: The Uses and Misuses of Civil Rights History. She argues that a simplistic and inaccurate narrative accompanied the erection of monuments to civil rights heroes and the creation of commemorations like the national holiday honoring King. The story we began to construct was a narrative that everyone could get behind, “a story of individual bravery, natural evolution, and the long march to a more perfect union,” she writes. “A story that should have reflected on the immense injustices at the nation’s core and the enormous lengths people had gone to attack them had become a flattering mirror.”

A new film MLK/FBI, by the acclaimed Emmy Award winning director Sam Pollard, speaks directly to the dissonance between our popular memory of the civil rights movement and its complicated history. Pollard, who is known as the editor on Spike Lee’s films, as well as for directing films on the civil rights movement like Slavery by Another Name and the classic “Eyes on the Prize” PBS series, wanted to create “a film about how [Dr. King] is considered an icon now but was considered a pariah back in the day.”

Based on newly discovered and declassified files, the film tells the story of the FBI’s surveillance and harassment of King. and explores the contested meaning behind some of our most cherished ideals. The Smithsonian’s History Film Forum is hosting an evening in conversation with Pollard along with Larry Rubin, a former field secretary of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), in a virtual event on Martin Luther King Day, Monday, January 18. Pollard’s film is in theaters this week and will soon be available for home screening.

Beginning around 1962, long before anyone could imagine King would be honored with a national holiday or even with a postage stamp, the FBI, led by J. Edgar Hoover, saw the civil rights leader as a serious threat to the nation. The FBI’s interest in investigating King was initially driven by his relationship with friend and advisor Stanley Levinson, introduced to King by Bayard Rustin, himself the subject of a government probe.

Hoover and William Sullivan, the FBI’s head of domestic intelligence, led an investigation into the relationship between King and Levison that eventually broadened into an effort to discredit and destroy King and the movement.

As Yale historian Beverly Gage says in the film, “the FBI was most alarmed about King because of his success and they were particularly concerned that he was this powerful charismatic figure who had the ability to mobilize people.” Hoover had famously said that he feared the rise of a black messiah, and as Gage has suggested he envisioned himself as not just a law enforcement official but a “guardian of the American way of life,” which included securing racial and general hierarchies that placed white men as the natural rulers.

Read about another iconic moment in civil rights history—the Greensboro Sit-In

As we learn more about the government’s campaign against King and the movement, it appears the surveillance and misinformation may have played a significant role in turning King into that “pariah.”

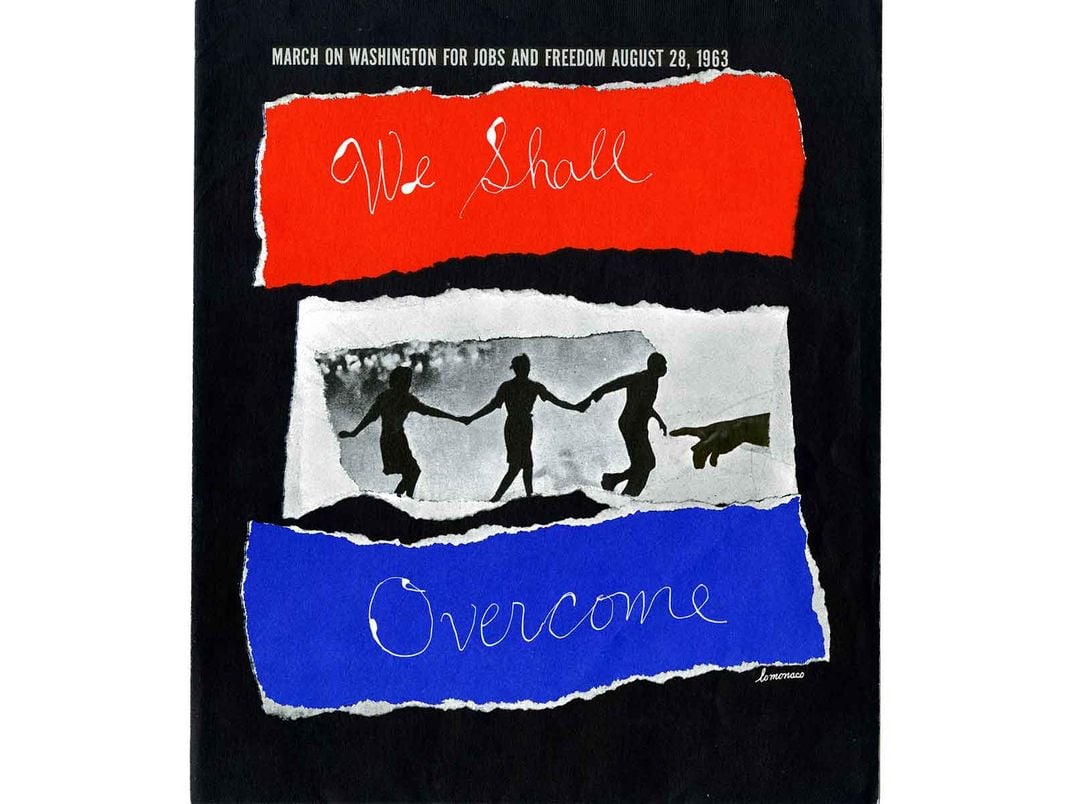

It began when King stepped down from the podium at the Lincoln Memorial after giving one of the most famous speeches in national and world history, his “I Have a Dream” speech. In this instance, the march brought together more people than had ever participated in such a protest in the nation’s history.

That iconic moment defines King and the ideal of protest for many Americans. It was also the moment that Hoover and the FBI wrote an urgent memo stating King was the “most dangerous Negro in the future of this nation,” and resolving to use every resource at its disposal to destroy him.

To dig up dirt on King, the FBI first centered on the relationship with Levinson to suss out possible communist ties to the movement. The government felt that communists threatened to subvert the racial hierarchy in America. Because of general fears of communism in the 1950s and 60s, it was also a convenient brush to paint dissenters with that which would play well with the public. National white leaders quite openly began to speak of the civil rights movement as being initiated and controlled by the American Communist Party and an international communist conspiracy.

This effort was not just directed at movement leaders at the level of King, but became a systematic effort to destroy the movement aimed at both its leadership and rank and file.

Rubin, then a 22-year-old white student organizer who became a SNCC field secretary, was traveling from Oxford, Ohio, with a carload of books to set up Freedom Schools in Mississippi. He was beaten and arrested numerous times and charged with attempting to “overthrow the government of the state of Mississippi” for his work to educate black children.

During one arrest, police took away his address book and soon after, to turn attention away from the disappearance of three civil rights workers who had been murdered in Mississippi, U.S. Senator James Eastland used the notebook as evidence against him. In a speech dripping with anti-Semitic overtones, he denounced Rubin and other activists as communists.

This period in 1964, a moment of great successes in the movement from the passage of the Civil Rights Act, to the Mississippi Freedom Summer project, to King’s Nobel Peace Prize, is also the period when the FBI’s work against King began to diminish the movement’s popularity. The agency’s campaign soon took a new direction from proving communist ties to, as King's biographer David Garrow states, a focus on “collecting salacious sexual material of King with various girlfriends.”

Unsealed FBI field reports later made public by the National Archives show the campaign used wiretaps and bugs to record King in sexual dalliances with women other than his wife and that this information was sent to reporters, clergy and others in the movement in an attempt to discredit him.

When this effort didn’t succeed in producing the destruction of King as Hoover and Sullivan had hoped, the Bureau stepped up its efforts. This time, they sent his wife, Coretta, a recording that was purported to be the civil rights leader with another woman. And the bureau sent the recording to his office with an anonymous letter supposedly from a disenchanted movement activist, suggesting that King should commit suicide before his sins were revealed to the public.

The story of the FBI’s campaign against King has clear and sobering relevance today. It reminds us of the danger of a powerful, unchecked and flawed demagogue like Hoover using his office to impose his own views on society and to enforce them with scurrilous and lawless methods. It speaks to the effect that that sort of rhetoric can create bias and scorn, whether terms like “communist” or “Antifa.” It also shows the power of elements of American culture like Hollywood films and television as complicit in the oppression of black Americans through the romanticization of an institution like the FBI.

Shows like the 1960s television series “The F.B.I.” helped lead a biased public to trust the agency and demonize black activists. Lastly this look back at a history that is so different from our collective memory of today, speaks to how we use the past to understand the present.

Was King a flawed individual? The unsealed and biased, but also personally damning evidence, about King’s infidelity creates a more complicated story about who he was and does not jibe well with the mythic memorial of statues and holidays. As former FBI director James Comey says in the film, “I’ve never met a perfect person.”

Pollard says he made the film in part to show that hero worship is dangerous. “When you elevate someone to be an icon, you forget that they’re human beings and complex. You forget that King did not do it by himself,” he says.

That is unless you remember King and the movement for what they were: committed individuals leading a people’s movement nonviolently grasping for the power available to them, against great odds and in the face of persecution and threat, and successfully making changes in the fabric of this nation. That memory of the movement and its leaders is not only more accurate history but is also more inspirational.

If change can only come through the work of perfect and heroic leaders enshrined in marble monuments, it leaves us waiting for one to arrive. A history embracing both the positive and the imperfect, with flawed people struggling against the odds should tell us that any one person may be able to similarly affect change.

“A Conversation with Director Sam Pollard, MLK/FBI” organized by the Smithsonian’s History Film Forum and the Smithsonian Associates, takes place online Monday, January 18, 2021 at 7 p.m., E.S.T. View the program live on UStream.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Kegley140407Wilson0014.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Kegley140407Wilson0014.jpg)