In a New Film, Master Artisans Share Their Passion for the Labors They Love

Award-winning filmmakers, Smithsonian folklorist Marjorie Hunt and Paul Wagner, explore impact of craft in Good Work, airing now on PBS

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/02/d1/02d1cb0e-5213-4e13-addb-5712a798bc80/crew_films_shoveling_copy.jpg)

“You’re always learning, always refining your skills. You never stop accumulating a more intimate understanding of your craft.” —Dieter Goldkuhle, stained glass artisan (1937-2011)

They use trowels and tongs, buckets and brushes, vises and pliers. They set blocks of limestone and carve rows of Roman letters and solder strips of lead and hammer pieces of hot metal. They are masons and metalworkers, plasterers and painters, carvers and adobe workers, and the filmmakers’ cameras followed them—all vital links between the past and the future, keepers of the building arts, masters of their craft.

They build. They adorn. They preserve. They restore.

And they do good work.

These artisans and their crafts are the subject of Good Work: Masters of the Building Arts, an hour-long documentary produced and directed by Marjorie Hunt, folklorist with the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, and Paul Wagner, an independent filmmaker.

Hunt and Wagner’s previous collaboration, the 1984 documentary The Stone Carvers, won both an Academy and an Emmy award for its account of the Italian-American stone carvers whose decades-long work adorns the Washington National Cathedral. This month Good Work makes its national debut, airing on local PBS stations and streaming on the PBS website. The film, Hunt says, is an “inspirational call to craft. This is dignified and important and satisfying work, and I hope the film can help people see that.”

Seventeen years in the making, Good Work has its roots in the 2001 Smithsonian Folklife Festival, where Hunt and her colleagues gathered artisans, including those featured in her film, for a ten-day program, “Masters of the Building Arts.” Over the course of the festival, Hunt observed the audience: “I saw this increase in understanding, this appreciation for the artisans’ skill and knowledge, this realization that these people weren’t just practicing their trade as a default or a Plan B because they had been unable to go to college. These craftspeople—their quest for mastery, their desire to excel, their intimate knowledge of the material, their deep connection with fellow craftspeople—were passionate about their work, about using their minds and their hands to make something that is lasting.”

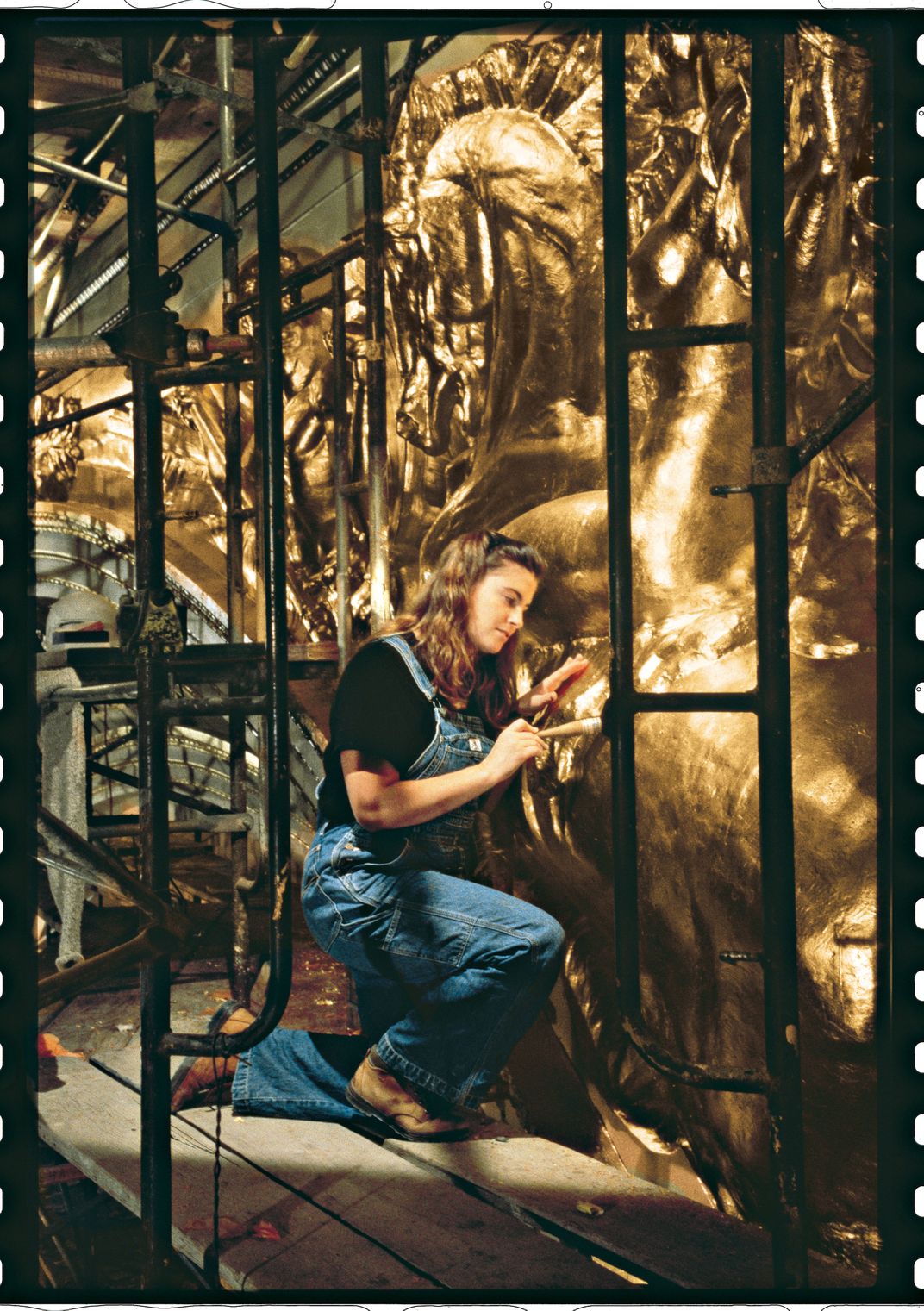

The film’s series of six-minute profiles documents the artisans as they go about their work and as they pause to reflect on the passions and processes and traditions of their trades: John Canning and daughter Jacqueline Canning-Riccio are preserving the John La Farge murals on the ceiling of Trinity Church in Boston; Patrick Cardine is hammering and bending a bar of hot metal in his Virginia studio; Albert Parra and his fellow workers are participating in an annual rite—the refurbishing of the adobe exterior on a 300-year-old morada in New Mexico.

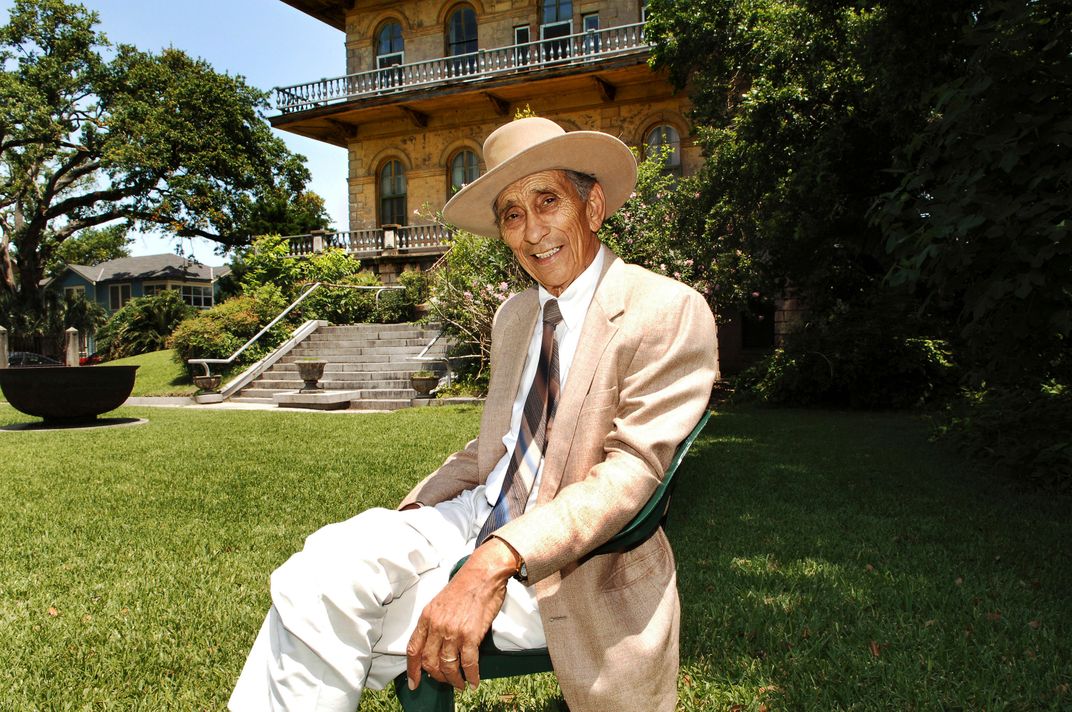

In a bittersweet turn, the film memorializes two of the craftsmen—Earl Barthé and Dieter Goldkuhle—who passed away before the film was completed. In New Orleans, Earl Barthé, a fifth-generation Creole of color plasterer, is restoring the decorative plasterwork of an historic home in New Orleans.

On a jaunt to the French Quarter, Barthé and his grandson Jamie visit St. Louis Cathedral, where Barthé and his brother, like their father and grandfather before them, can claim as their own a portion of the building’s history. Seated in a pew, Barthé waves his arm and draws Jamie’s attention upward, musing about visitors who might have gazed at the glorious vaulted ceilings: “They look so beautiful! I wonder did they ever stop to think, ‘Who done that work?’ Somebody—some plasterer—done that work.” Up there lingers the legacy of Barthé and his ancestors.

That legacy of excellence, often unseen, unnoticed, unrecognized, has something to do with the soul of a building. By way of example, preservation architect Jean Carroon, who supervised the restoration of Trinity Church, cites a series of 12 intricate paintings by La Farge—a portion of the Cannings’ restoration work for the church. The paintings, 120 feet above floor level, are virtually lost to view. At the National Building Museum recently for a screening of Good Work and a panel discussion, Carroon observed, “Nobody can see the paintings, but somehow, the fact that they are there is part of what makes the space resonate so much. You feel how many hands have touched that space, how much love and care have gone into it.”

Surely, the late Dieter Goldkuhle, a stained-glass artisan who created more than 100 windows for the Washington National Cathedral, understood that setting aside ego, even in the impossible pursuit of perfection, is part of the ethos of craft. Good Work captures Goldkuhle at the Cathedral, where he is removing an early and now buckling stained-glass window, and in his studio, where he places a large sheet of white paper over the window, rubbing a pencil across the lead ridges, to create a record—a key for later reassembly of the glass pieces, when Goldkuhle secures the piece of glass on the panel with channels of bendable lead.

“I do not design my own work,” he says in the film. “I have been quite content with working with a number of artists in a collaborative effort to be, somehow, the midwife to the window, comparable to what a builder is to an architect, a musician to a composer. I feel, also, that I am married to the material, which I just adore and have the greatest respect for.”

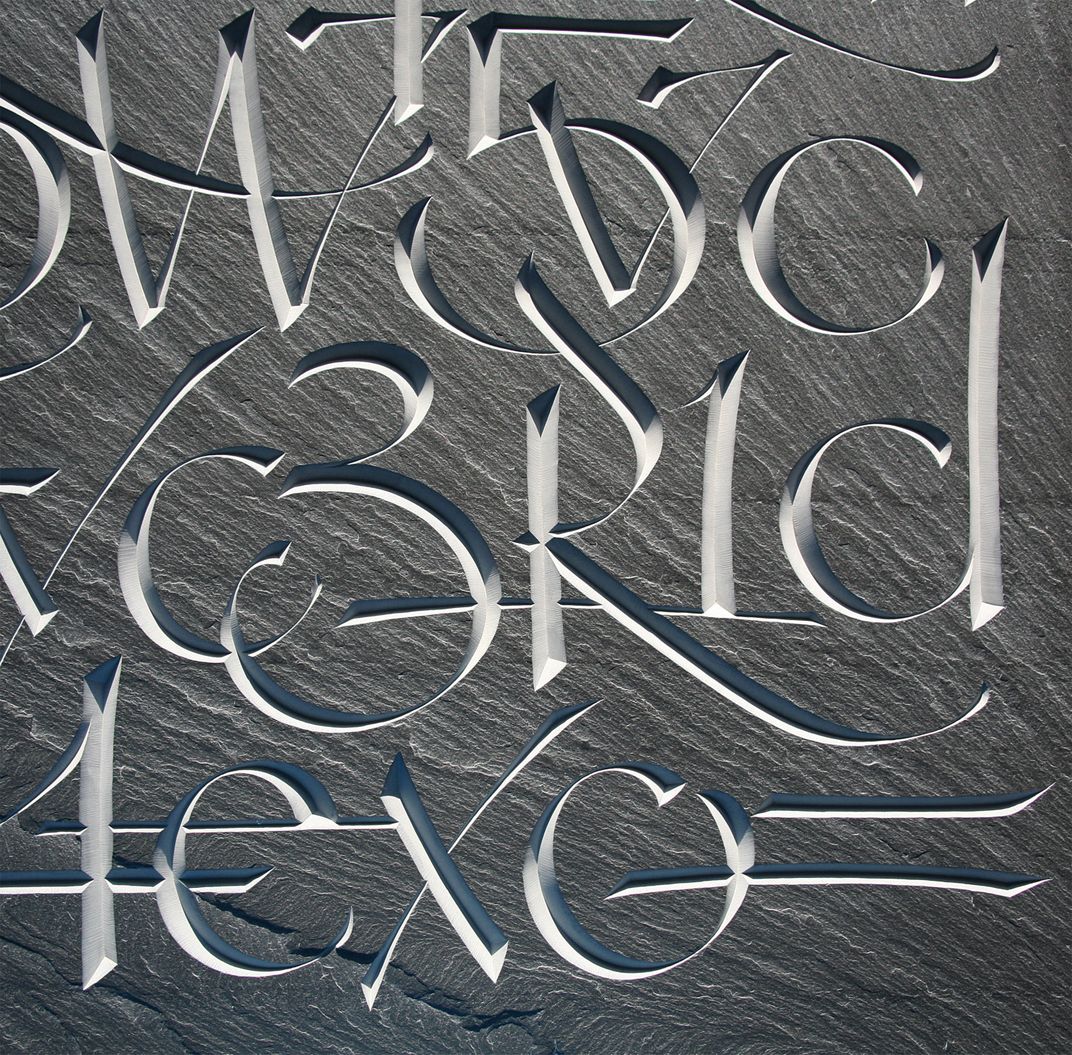

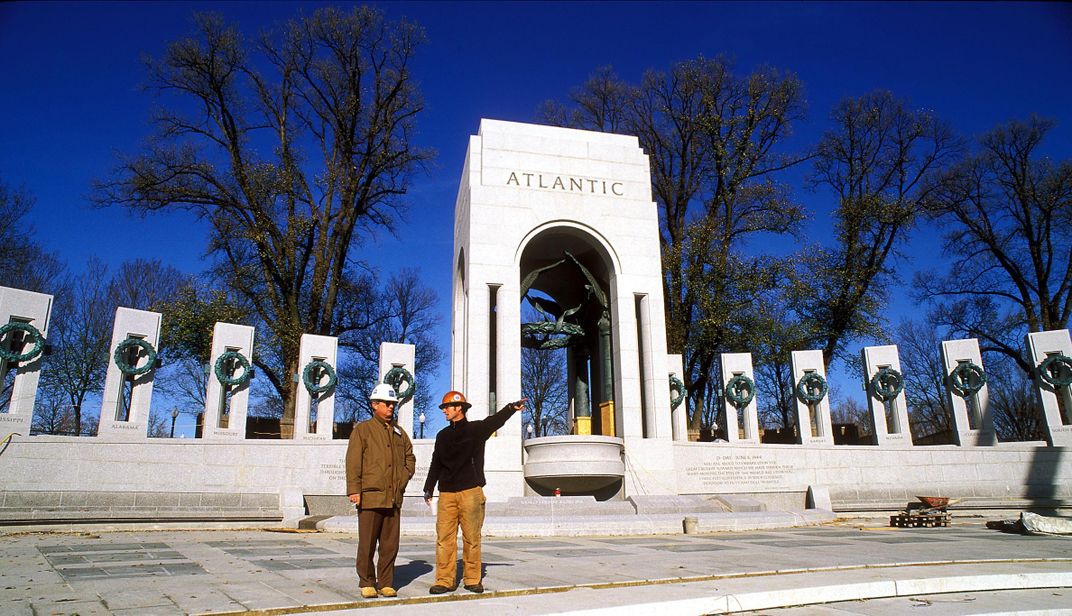

The film also highlights the work of Nick Benson, stone carver, calligrapher, designer and 2010 MacArthur Fellow. Viewers meet Benson both in his Newport, Rhode Island, studio, the John Stevens Shop, and in Washington, DC, on the then-construction site of the National World War II Memorial. At the busy site, Benson—wearing a hard hat, open-fingered gloves and protective goggles—guides his power chisel through the granite, forming the shallow trenches and sharp edges of a single letter. Later, he fills the pristine cuts with black stain, taking care to stop shy of each edge, lest it bleed beyond the confines of the letter. But in the end, it is the content of the inscription that the letters serve, however fine the hand-wrought aesthetic and humanity of his work may be. “That’s the funny thing about good lettering—they don’t even see it,” Benson says of visitors to this or any monument. “They don’t understand it. They take it all for granted. So, my job is to make something that people take for granted because it works so beautifully they don’t even think twice about it.”

Benson, the son and grandson of renowned stone carvers whose work adorns the U.S. Marine Corps’ Iwo Jima Memorial, the National Gallery of Art and the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial, grew up steeped in the craft, carving letters on gravestones when he was a teenager.

“You spend years learning just how far to push the material before you get into serious trouble,” he said in a recent interview. “That skill that is established before you are ever allowed to carve on anything of any value.” But the time came when Benson, aged 18, found himself at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., where his father was working on a project in the West Building’s Rotunda. Ushered onto a hydraulic lift, Benson found himself aloft, facing a wall, his father instructing him to carve one of the headings for the growing list of museum trustees.

“That’s 120-year-old Indiana buff limestone that doesn’t exist anymore. There I am, about to sink a chisel into this wall. I was petrified.” But once he started carving, the fear subsided. Benson’s father—“he had a perverse joy in throwing me into the deep end of the pool”—knew that his son was ready. And now, more than 30 years later, Benson regularly returns to the National Gallery to add inscriptions to that trustees wall. Does he check on that early work? “Sometimes, I’ll go all the way to the top and see how it looks.”

The filmmakers’ cameras followed Joe Alonso, master mason, to the Cathedral, where he has worked since 1985. Alonso is setting a block of limestone, which dangles from a nearby chain hoist. With a few swift strokes of his bucket trowel, Alonso spreads a bed of mortar atop an already-set block, “fluffing” the paste to create low ridges and troughs that will hold a light sprinkling of water. He buries little lead “buttons” in the mortar, a trick of the trade that will preserve a quarter-inch joint between the layers of blocks. Lowering the block onto the mortar bed and checking its alignment with a level, Alonso delivers a few quick strikes with his rawhide-tipped mallet. Done. “On a hot day,” he says, “you’ve probably got about two minutes to get that stone where you want it.”

Like Benson, himself a third-generation stone carver, Alonso, the son of a Spanish-born mason, straddles the workaday present and the still-living past, keenly aware of the men, the teachers, now gone, who cut and carved and set so many of the blocks—by today’s count, some 150,000 tons of stone—one by one, forming the Gothic structure—its nave, its apse, its transepts, its towers, its buttresses. In his early years at the Cathedral, working on the construction of the west towers, Alonso would look eastward, along the roofline of the completed nave, and sense the presence of his predecessors: “I was always aware that all those guys who had come before me were right there, in spirit, watching me,” he said, in a recent interview. “I thought that—I really did.”

That intimate connection with the past helps define “good work.” “When you work on a cathedral or a monumental building, you know there were generations before you working on that same structure, so ‘good work’ means being as good as those who came before you—trying to do as well as they did, because they passed their knowledge on to you.”

The masters featured in Good Work form an elite group. Few can do what they do. But, as Paul Wagner, Hunt’s partner in the project, suggests, their work ethic can be our work ethic. “If only all of us could bring their level of care, attention, respect, integrity, honesty and beauty to what we do,” Wagner says. “The film is a lesson in how we can approach work in our own lives.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5d/14/5d14caa6-bbb9-45e9-b194-f0ffd474e667/canning-jackie-john-daubing-stencil.jpg)