A New Show About Neighborhoods Facing Gentrification Offers a Cautionary Tale

As cities face multi-billion-dollar developments, the question remains “Who Owns the City?”

:focal(1445x1472:1446x1473)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e9/8a/e98a3e0b-7a9d-4a75-be88-c3f46d618842/adams-morgan-image.jpg)

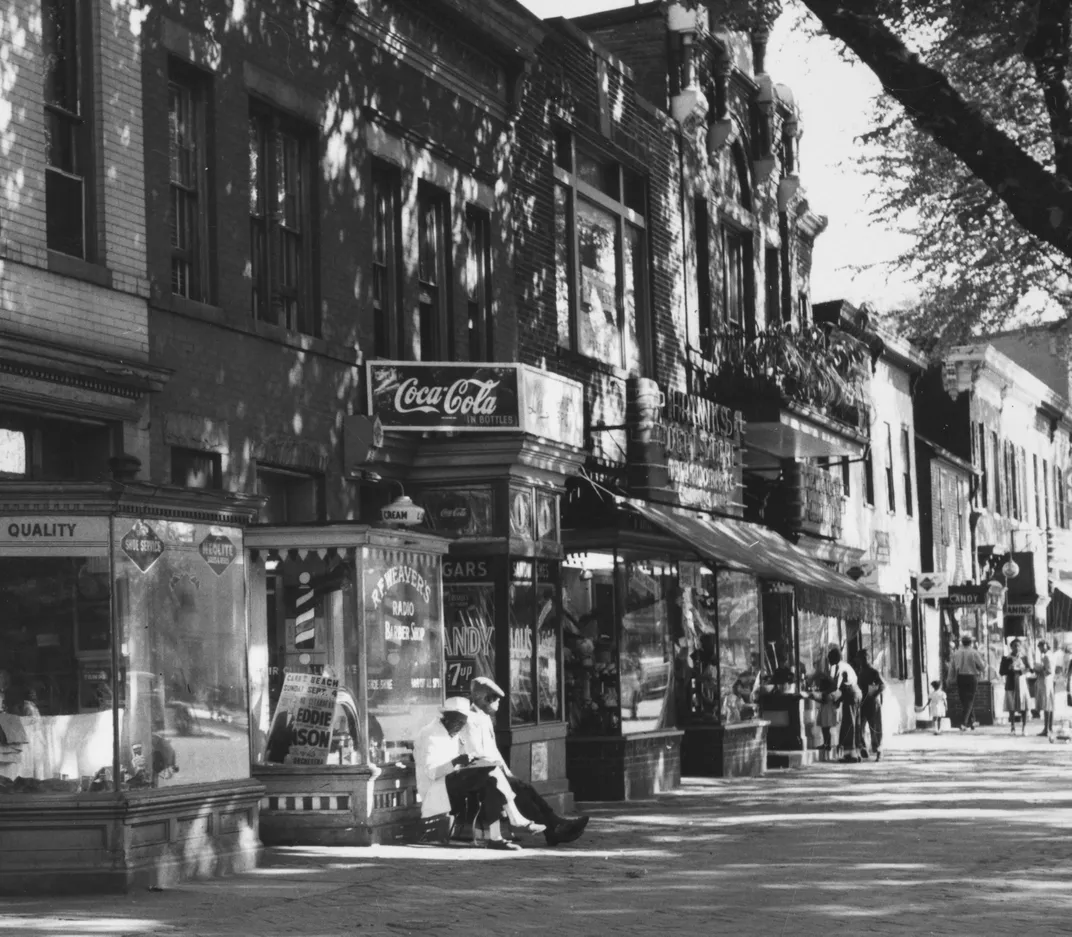

A 1949 black and white photograph of 4th Street in Southwest Washington, D.C., might shock the affluent residents who live there now. It shows the commercial district of a vibrant African-American community—with barbershops, department stores and candy shops. It was a thriving, working-class neighborhood where mostly black and some Jewish residents lived, worshipped, played and went to school. In the midst of rivers and canals, small brick and frame houses lined the streets of this self-sufficient, close-knit community. But its proximity to the National Mall and the federal government’s seat of power put it in the crosshairs of a growing sentiment in the 1940s and 1950s for the need for city redevelopment.

“Southwest was ground zero in many ways,” explains Samir Meghelli, curator of the exhibition “A Right to the City,” currently on view at the Smithsonian’s Anacostia Community Museum. “We really begin with the federal policy of urban renewal, and the idea was that so much of the city centers were seen and perceived as ‘blighted.’ These were communities that were not exclusively, but were mostly African-American working-class communities, and Southwest Washington, D.C. was one of the first neighborhoods to be targeted for urban renewal.”

The exhibition, sourced with photos, videos, artifacts and nearly 200 oral histories, transports visitors back to seminal moments in the District’s history as residents fought to preserve neighborhoods and control the rapid transformation driven by development. Meghelli says the questions asked here resonate far outside of Washington, D.C.

“The title of this exhibition tries to get at the heart of the matter, which is this question of whether people have a right to the city, or the right to access the resources of the city,” Meghelli explains. “Do people have equal access to the opportunities provided by the city? The important global context is that for the first time in human history more than half of the world’s population lives in cities, and cities are growing at an unprecedented pace.”

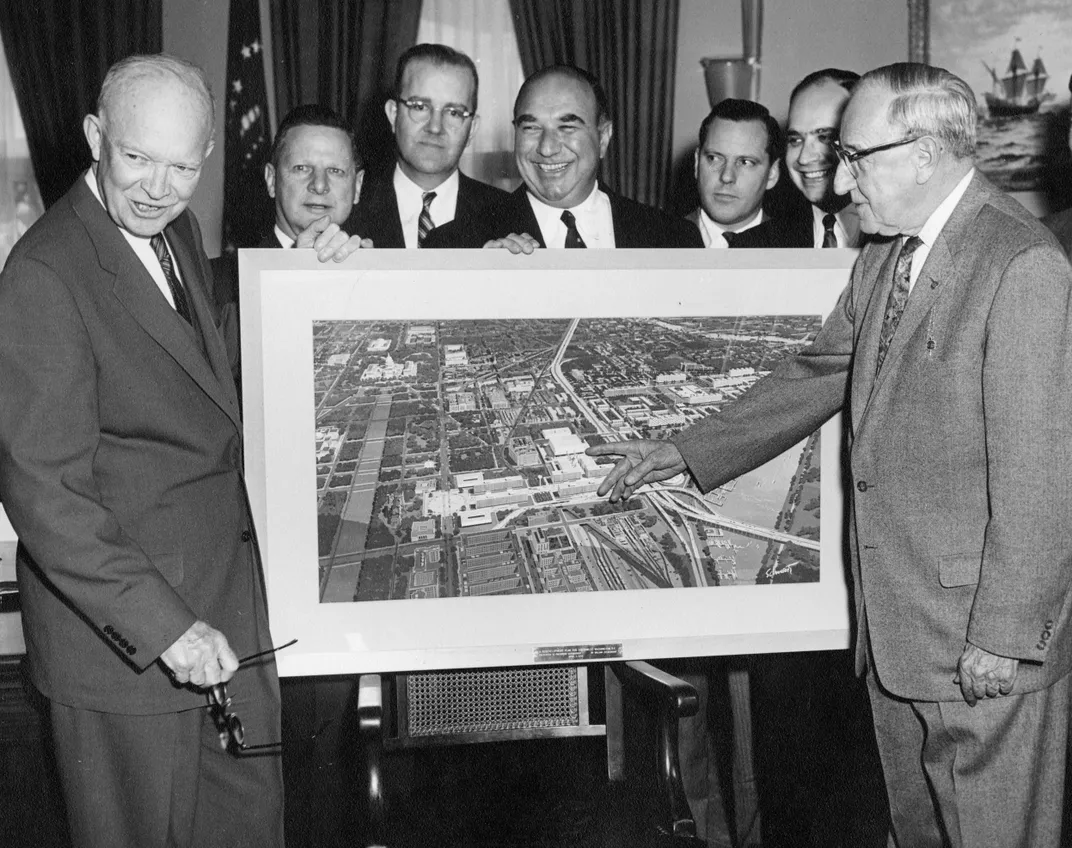

One of the oldest neighborhoods in the District of Columbia, Southwest sits south of the U. S. Capitol building and the National Mall, so politicians decided it was the perfect opportunity to try out this policy of large scale demolition and “slum clearance,” Meghelli says. There’s a 1958 picture of President Dwight D. Eisenhower reviewing Southwest D.C. urban renewal plans with developers William Zeckendorf, Sr., and John Remon. There’s also a 1959 photo of rubble from destroyed buildings at 11th Street and Virginia Avenue S.W., with the Washington Monument gleaming in the background. A large synagogue, called Talmud Torah, was built in the neighborhood in 1900. It was torn down in 1959.

As wrecking crews demolished the neighborhood, some small business owners sued to remain in their properties. But the landmark 1954 Supreme Court case, Berman v. Parker, affirmed that the government has the right to seize private property for public use as long as just compensation is provided. That ruling is still used today in eminent domain cases, including the 2005 case in New London, Connecticut, that went to the Supreme Court. By the early 1970s, more than 23,000 people had been displaced, as well as more than 1,800 businesses. National figures such as author James Baldwin described urban renewal as “Negro removal.”

Many of those displaced from Southwest D.C. ended up in Anacostia, a neighborhood that lies immediately east of the Anacostia River and is home to the museum. Curator Meghelli says the exhibition tells the history of this now rapidly gentrifying area with a narrative—segregation, desegregation, resegregation.

“When Anacostia was founded in the mid-19th century, it was founded exclusively as a white neighborhood with restrictive covenants that meant that only whites could purchase homes there. Alongside that,” Meghelli says, “you had a free African-American community called historic Barry Farm Hillsdale, so you had these two segregated communities—one white, one black—living side by side.”

But a movement to desegregate the District’s deeply unequal schools and public accommodations led to protests in the 1950s. The historic 1954 Brown v. Board of Education case that desegregated the nation’s schools didn’t apply in the District of Columbia. But a companion lawsuit, Bolling v. Sharpe, involving the newly built whites-only John Philip Sousa Junior High in Anacostia, ultimately led to the desegregation of schools in the District. Photos in the exhibition show protests against integrating the schools in Anacostia, including images surprisingly similar to those from Little Rock, Arkansas.

“You can see on the front of the stroller here the mother put a sign that says ‘Do we have to go to school with them?’ So, I think people don’t have the sense that this was something that was happening in Washington, D.C.,” Meghelli says. “The desegregation of the schools is part of what began transforming neighborhoods like Anacostia.”

People in other parts of the District, including the historic Shaw neighborhood that housed the famous Black Broadway along U Street in Northwest D.C., looked at what had happened in Southwest and determined to block the wholesale demolition and displacement. “A Right to the City” chronicles the battles of Rev. Walter Fauntroy, who in 1966 founded the Model Inner City Community Organization (MICCO), which worked to make sure residents and small business owners helped lead the urban planning process in a way that would serve their interests.

“MICCO hired black architects, black construction engineers. It just really built a powerful kind of collective of not only planning professionals but also just residents and small business owners who began planning for the renewal of their neighborhood,” Meghelli says, adding that one of the stories the exhibition tells is about the building of the Lincoln-Westmoreland Apartments at 7th and R Streets NW. MICCO collaborated with the African American Temple of Shaw and the predominantly white Westmoreland Congregational Church of Bethesda, Maryland, to create affordable housing, the first building to be constructed in the aftermath of the 1968 riots following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. It still stands today, despite the rapid changes happening in the neighborhood.

“It’s one of the few remaining affordable housing options . . . so many of the buildings that are affordable housing in a rapidly gentrifying neighborhood are the result of this organization (MICCO). It’s kind of a powerful story of how a neighborhood responded to what was happening in Southwest,” Meghelli explains.

The advocacy group One DC, is continuing to fight for racial and economic equity in Shaw and in other parts of the District says long-time resource organizer Dominic Moulden, who started working in D.C. in 1986. But he says several things need to occur for the history and culture of working class African-Americans to be preserved in neighborhoods such as Shaw, which now boasts a rooftop dog park and beer gardens.

“One DC and our solidarity partners need to continue to make strong commitments to grass roots base-building organized around housing and land. Just as the title of the exhibition says we need to fight for the right to the city, meaning we should go as far as we need to go to make sure no black people, large black families, Latino people . . . immigrant people . . . do not get removed from Shaw because whether they are low income or middle income they have a right to the city,” Moulden declares.

That work, he says, includes building strong tenant associations and strong civic associations that will fight for the people who live in Shaw. He adds that “the people” need to take back public land and control public facilities, and make sure any developments with public subsidies include housing for low income and working class people. Moulden says the battles of the 1960s in Shaw, where Dr. King spoke in 1967, have strong lessons for those continuing to work to help regular folk survive in an increasingly expensive city and in others around the nation and the world.

“I think they believe we have more power than we have—that we won more than what we have because we’ve done more than other cities. But the bar is so low we want to raise the bar,” Moulden says. “So looking at the two or three parcels of land and the buildings we helped people buy, why couldn’t we help more people buy and control their whole neighborhood?”

He points to the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative in Roxbury, Boston, a community-based organization that used eminent domain—a tool often used by developers to gut neighborhoods—to rebuild a ravaged area with affordable housing, parks, gardens and new businesses. Moulden thinks similar methods could be used in the District, along with more political education so people will be more aware of the housing crises many neighborhoods are facing. He also thinks those organizing to save their homes and businesses from displacement should be suspicious of developers offering gifts, and promising to move people back into their residences once housing has been demolished.

“You should always be suspicious when you see a private developer or the government in most cases or even influential people talk about equitable development,” Moulden says. “They’re not talking about keeping black people and working class people in place. They’re not talking about having those people at the table making decisions. . . . They are neglecting these communities so they can build them for somebody else.”

One DC, he says, is continuing to fight in Shaw, and in Anacostia, where the organization “put up its flag” at the first building it has ever owned. Moulden stresses that similar battles are being fought around the world, from the Landless Movement in Brazil to the battle for affordable housing in London.

In Adams Morgan, a neighborhood in Northwest D.C., community organizer Marie Nahikian says the battle for equity happened a little differently than it did in the city's other neighborhoods. In the 1950s, parents and teachers at two formerly segregated elementary schools, John Quincy Adams and Thomas P. Morgan sought to facilitate integration there. The organization they created, the Adams Morgan Better Neighborhood Conference, tried to create a sense of community in a neighborhood with a large income and wealth gap, as well as attempt to control improvements there without the massive displacement of its lower income residents.

“What happened in Southwest was really government initiated, and what’s happening in Shaw now is closer to what I think we saw in Adams Morgan in that it was largely happening in the private market,” Nahikian explains. “What happened in Adams Morgan, there was not the stark racial divide because we really were racially diverse, and the group that came together in Adams Morgan was also economically diverse.”

She says that meant that even people who lived in the expensive houses in the Kalorama Triangle understood that what happened on Columbia Road affected their lives as well. There was large scale displacement of blacks, whites and Latinos in the 1970s, but people there with the help of the Adams Morgan Organization (AMO) won some huge fights around housing and tenant’s rights. Nahikian remembers getting a frantic phone call in the mid-1970s about a situation on Seaton Street.

“‘You better get down here right away,’” Nahikian, who was working with AMO at the time, recalls the voice on the phone saying. “‘Everybody just got eviction notices!’”

More than 20 people were about to lose their property to a single developer, Nahikian says, some of whom had lived there for decades. There were multiple generational households, and the block was full of children, so AMO challenged the evictions in court. At that point, she says there were no regulations written for a tenant’s right to purchase.

“We ended up settling and the families were offered the right to purchase their homes for a set price,” says Nahikian, who recalls similar battles in other parts of the neighborhood. She also tells the story of rolling a huge wooden box television which played a video made by a neighborhood group of young people called the Ontario Lakers to convince Congress to fund the purchase of Walter Pierce Park. In the last few years graves from a Quaker and African-American cemetery were found in the park.

Not only did Adams Morgan’s AMO become the role model for the District’s advisory neighborhood commissions, Nahikian says the activists’ battles there helped create legislation including the Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA). She says the first-time advocates were successful in enforcing the tenant’s right to purchase was on Seaton Street. But last month, the District’s City Council changed that legislation, exempting renters of single-family homes, among other things, a move that infuriates Nahikian.

“Didn’t we learn anything?” Nahikian wonders.

“So, we’re right back to the exhibit, ‘A Right to the City.’ But the package of the regulatory framework that we created that really came out of Adams Morgan initially that we created in the District of Columbia has survived for 50 years and it could be used all over the country,” says Nahikian.

But she worries that the drive that kept advocacy organizations in the District fighting for equity and housing and tenants rights doesn’t exist anymore at a time when those issues are a nationwide problem.

“The scariest part of all for me is that the U.S. government is the largest owner of low-income affordable housing in the world. . . . You look at where public housing exists nationally now and it is on the most desirable land, and the pressure from private developers to take over is humungous,” Nahikian says.

Back in Southwest D.C., cranes are swinging as work continues on many developments, including The Wharf, a high-end mix of housing, retail, office and hotel space. The nearby long-standing public housing development Greenleaf Gardens is slated for demolition, and some in the area worry that middle and low-income residents won’t be able to afford the neighborhood for much longer.

The museum’s curator Meghelli says that is one of the things he hopes people think about when they see this exhibition, recalling the message in the speech King made in Shaw in 1967.

“’Prepare to participate,’” Meghelli says was King’s refrain. “It’s kind of an important thread throughout this exhibition. . . . We are all complicit in the changes that are happening in our cities whether or not we are actively involved. We need to . . . participate in the process in order to actually shape as best we can the kind of change that is happening in our cities.”

"A Right to the City" is on view at the Smithsonian's Anacostia Community Museum, 1901 Fort Place, S.E., Washington D.C., through April 20, 2020.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)