New Species of Ancient Dolphin Shows How the Animals Moved From Seas to Rivers

The newly discovered fossil gives scientists a fresh glimpse into the evolution of ocean life

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/68/61/68616033-ce3a-439e-a9b6-66dc8c5a0856/skull1web.jpg)

Six million years ago, the oceans teemed with marine life of all kinds—from pygmy sperm whales to sailfish to dolphins. But why did some dolphins stay in the sea, while others migrated to rivers? A newly discovered genus and species of long-extinct dolphin is helping answer that question.

Today, a team from the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History and the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama announced the discovery of Isthminia panamensis, an extinct dolphin that lived in the ocean but shares features with modern-day, freshwater dolphins found in coastal and freshwater habitats like the Amazon River.

You might think that finding, understanding and naming an entirely new genus and species would be old hat to a team of experienced experts. And that’s where you’d be wrong, says Nicholas D. Pyenson, curator of fossil marine mammals at the Natural History Museum in Washington, D.C., and leader of the multinational team that just published their findings in the scientific journal PeerJ. Isthminia panamensis’ journey from a curiosity to an unquestionable new genus was anything but straightforward.

It began with a race against the tides.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/30/d8/30d8e751-f0a5-4b12-af32-5a3bd9342388/aza8092web.jpg)

In 2011, Pyenson got a call from a colleague in Panama. Evolutionary biologist Dioselina Vigil had discovered a fossil of a toothed whale in an exposed rock in an intertidal zone off the coast of Piña, on the Caribbean side of the isthmus.

Pyenson and his team raced off to Panama with a whale of a task: They had to work rapidly on the beach at low tide to excavate the fossil. With a window of four to six hours in which to accomplish two days’ worth of excavation work, the team dug up the specimen, placed it in a plaster jacket, pried it from the site, flipped it and pulled it to safety—just ahead of the high tide.

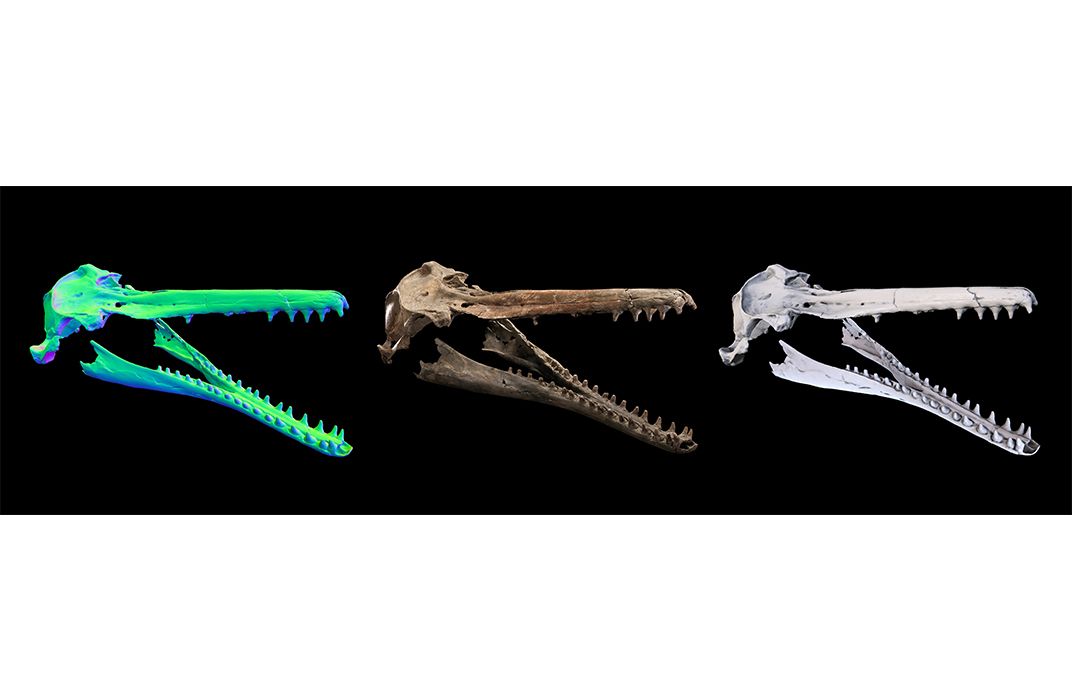

When he looked at the specimen, Pyenson could see a long snout that seemed to link the fossil to the now-extinct family of Squalodontid shark-toothed dolphins. The team nicknamed the fossil “Squaly.” With the proper permits in place, and with the agreement of the Panamanian government, they shipped it back to Washington, D.C., and were gratified when the find (rare for whales or dolphins of that time period) got plenty of positive attention.

But as the team got deeper into preparation of the fossil in Pyenson’s lab, the plot thickened. As they used everything from power saws to dental picks to carefully extract the fossil from its matrix of sand and rock, Pyenson and his team started to realize that “Squaly” looked more like a freshwater river dolphin than anything that can be found in the ocean. It had a configuration of bones above its face and eyes that is similar to one found in river dolphins.

Pyenson puzzled over how a creature so similar to river dolphins could have started out in the ocean—after all, the site it had come from was definitely a marine habitat.

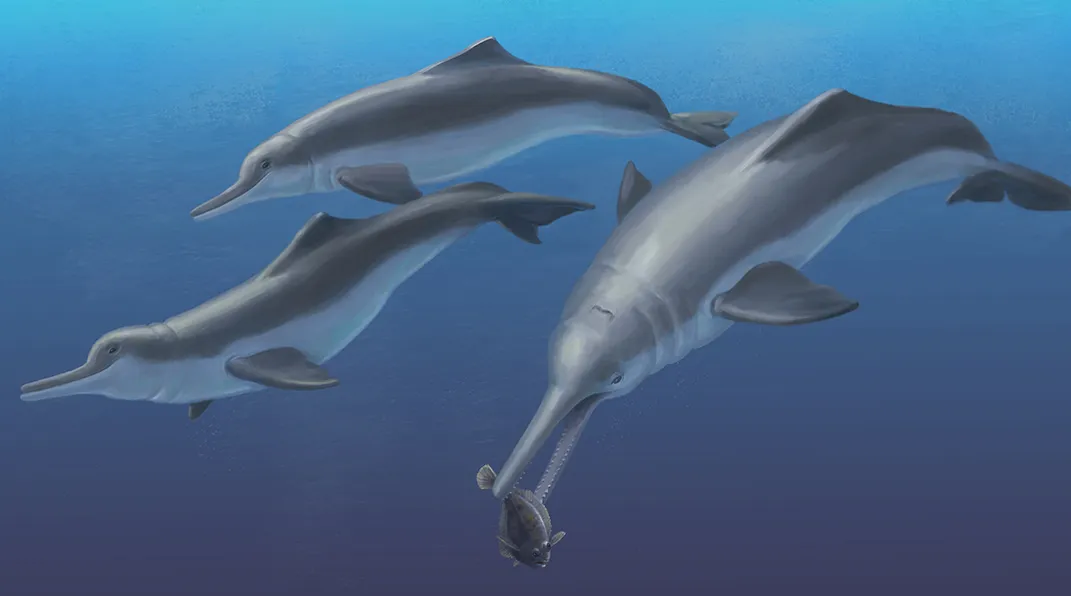

After two years of analysis, including the creation of a painstaking 3D model, the team got an answer to the conundrum. Pyenson and his co-authors now contend that the fossil represents not just a new genus and species, but an important peek into the period when some ancient dolphins made the journey from sea to river.

The find, says Pyenson, represents “more fossil material than we have for anything else that could possibly be related to the river dolphin,” proving that dolphins couldn’t have invaded Amazonia before some point between 5.8 and 6.1 million years ago.

Isthminia panamensis “probably had a pretty toothy grin,” says Pyenson. He compares its appearance to that of the modern-day bottlenose dolphin—and it may have been pink in color.

The nickname “Squaly” doesn’t apply anymore: The dolphin now has a much fancier moniker which pays quadruple tribute to the biologically influential isthmus of Panama, the Amazon river, the people of the country of Panama and the scientists who study there. And that’s okay by Pyenson. Though he admits the team has given the fossil another nickname, he’s keeping it a closely-guarded secret. After all, he’s proudest of its new scientific name: “It’s a much more interesting story now.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)