There’s More to This Towering Pink Easter Bunny Than Kitsch

Evoking springtime and rebirth, African burial ritual, rhythm, and identity, the “soundsuit” by artist Nick Cave is packed with iconic themes

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cc/3e/cc3e9fbe-e0c6-4c37-b1ea-a4e7bcd05071/0921v12013webjpg.jpg)

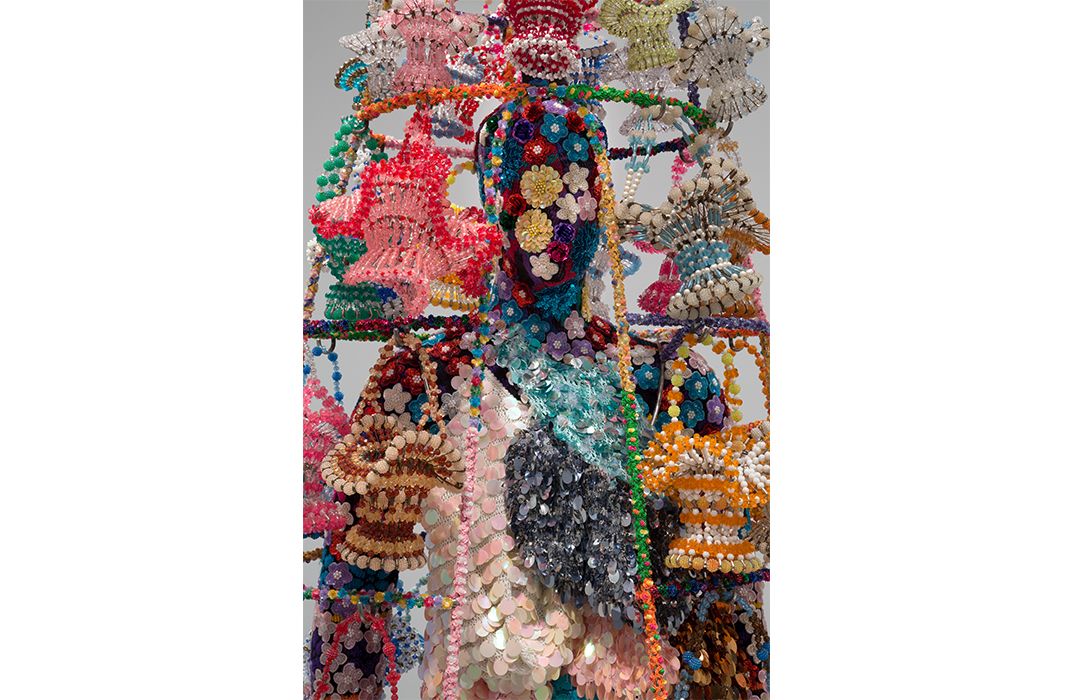

At 11 feet tall, it stands—towers, really—over the viewer. A riot of color erupts from a pyramid-like frame hung with red, green, blue and orange baskets made from beaded safety pins. Beneath them stands a faceless mannequin covered from head to toe in a black and fuchsia bodysuit.

At the very top, the pièce de résistance: a papier-mâché bunny, accented in cotton candy pink, with cartoon eyes and a vague, slightly unnerving smile. The bunny holds an egg, inscribed with the message “Happy Easter.”

Those familiar with the work of artist Nick Cave will quickly recognize this 2009 work as one of his signature “Soundsuits,” and therein lies a sweeping, decades-long saga of wearable sculptures made from found objects.

The piece, currently on view at the Hirshhorn museum, is a perennial favorite among visitors. “It’s fun, it’s kind of humorous, it’s over the top, and it’s something that people can relate to,” says curator Evelyn Hankins. “But I think what’s so interesting about Cave’s work is that these Soundsuits are meant to be worn. They’re performative.”

Cave, a Missouri native who is now the chair of the fashion department at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, studied both fine art and dance as a young man. He received his MFA from Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan in 1989, but also spent time in New York, studying with the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre.

In the wake of the Rodney King beating in 1991, Cave found himself in the park one day, “feeling discarded and dismissed” as an African American male. He bent down and picked a twig up off the ground, and then another, fastening them together in what he has described as an effort to protect his own identity from the outside world.

It wasn’t until a form began to take shape that the idea of movement occurred to him. “I was building a sculpture, actually,” he says. “And then I realized that I could wear it, and that through wearing it and movement, there was sound. So then that led me to think about [how] in order to be heard you had to speak louder, so the role of protest came into play. This is really how Soundsuits sort of evolved.”

Since then, Cave has produced more than 500 widely acclaimed Soundsuits in a dizzying array of materials and silhouettes. The works have resulted in several public performances, including 2013’s HeardNY at Grand Central Terminal.

The Soundsuits have evolved over the decades, but their fundamental tenets remain unchanged. All are built from found or discarded objects; they conceal all indicators of race, gender or class; and they are meant to be worn in performance, or at least to suggest the idea of performance, as is the case for the piece at the Hirshhorn.

Artists have used found materials in their work since the early 20th century, when Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque and others began incorporating newspaper clippings and other quotidian objects into their sculpture, collage and assemblage. Cave continues in this vein, most recently favoring vintage craft items, which he sources from antique markets across the country and internationally.

“They’re not traditional art materials, they’re decidedly craft materials,” says Hankins. “You don’t find big Easter bunnies in art galleries, usually.”

As it turns out, it was the Easter bunny – not a sketch or blueprint – that served as the instigator for this particular piece. “I loved this sort of reference to a particular period in my upbringing as a kid and with my seven brothers and being dressed up at Easter and having these amazing, sort of outrageous Easter hunts on the farm… But feeling at that time as a kid that you were authentic and you were lovely and beautiful because that’s what you were told.”

Cave’s process is highly intuitive, and he says that once he decided to place the bunny at the top of the sculpture, the piece truly began to take shape. As it progressed, it gathered new layers of significance, evoking ideas of springtime and rebirth, African burial ritual, rhythm, identity, high and low art, color, movement and of course, sound.

In Cave’s hands, items are valued as much for the nostalgia they elicit as for their potential to be removed from their original context. One does not expect to see twigs, noisemakers, porcelain bird figurines, or Easter bunnies at a museum, but when presented as part of a Soundsuit, the viewer imagines the materials swaying, jingling, swishing, or clanking together in a surprising way. These objects, which would otherwise be cast off as “low art,” produce an entirely new sensory experience.

The Hirshhorn’s Soundsuit is currently on display in “At the Hub of Things,” the museum’s 40th anniversary exhibition. Hankins says she and co-curator Melissa Ho decided to organize the show by grouping together artists from different periods around loose themes. The Soundsuit shares a gallery with works by Christo, Claes Oldenberg and Isa Genzken. The oldest work is Robert Rauschenberg’s Dam, a 1959 combine created the same year Cave was born.

“Rauschenberg of course was famous for talking about wanting to bridge the gap between art and life – or working in between the two,” says Hankins. “I think that one of the things museums are grappling with right now is how to document and capture performance, which is by definition an ephemeral event. Like Rauschenberg bridged the gap between art and everyday life, Cave bridges the gap between static objects and performance.”

Cave’s work might be remembered for forcing the art world to reconsider this divide, but what makes his work so appealing is that it touches on so many different themes. “It can speak to collage and assemblage, it can speak to performance, it can speak to ideas about authenticity and originality, and the role of the artist and originality in art, and all of these other things,” says Hankins. “And I think that’s one of the reasons why Cave is so respected, is because the work—especially in the case of our piece – the work at first seems like it’s just kind of funny and kitschy, but in fact it’s this very serious engagement with these various themes and history.”

Cave says he has often witnessed viewers engaged in spirited conversation about his work. This is precisely the effect he is aiming for: “I want the viewer to be able to look at the work and we can talk about multiple things. But it doesn’t set within only this one way of thinking about the object. We can talk about it as a decorative object. We can talk about it as a sculptural form. We can break it down and talk about individual pieces within the overall whole. We can talk about pattern. We can talk about color. We can talk about rhythm, sound. So it really becomes more universal in its message.”

More than 20 years after Cave picked up that first twig, the emotional impetus for the Soundsuits remains more relevant than ever. The artist says he is currently working on a series about Trayvon Martin for an upcoming show in Detroit. He says he also plans to address some of the more recent instances of racial profiling in places such as Ferguson and New York.

“All of these incidents that have happened within this past year were just outrageous,” says Cave. “At this point, I’m working towards what I’m leaving behind. But I just think this work can never ever end.”

See Nick Cave's Soundsuit, 2009 at the Hirshhorn's exhibition "At the Hub of Things: New Views of the Collection," currently on view on the museum's third floor. The show reveals a fresh perspective on the museum's modern and contemporary art holdings and showcases recent gallery renovations. On view in definitely, the exhibition includes large-scale installations by Spencer Finch, Robert Gober, Jannis Kounellis, Bruce Nauman, and Ernesto Neto, as well as paintings and sculptures by Janine Antoni, Aligheiro e Boetti, Cai Guo-Qiang, Isa Genzken, Alfred Jensen, and Brice Marden, among others.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jess-righthand-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jess-righthand-240.jpg)