Not Too Hot and Not Too Cold, These Goldilocks Planets are Just Right

At the Air and Space Museum, a new sculpture debuts, showing all of the stars with orbiting “Goldilocks planets,” those that could sustain life

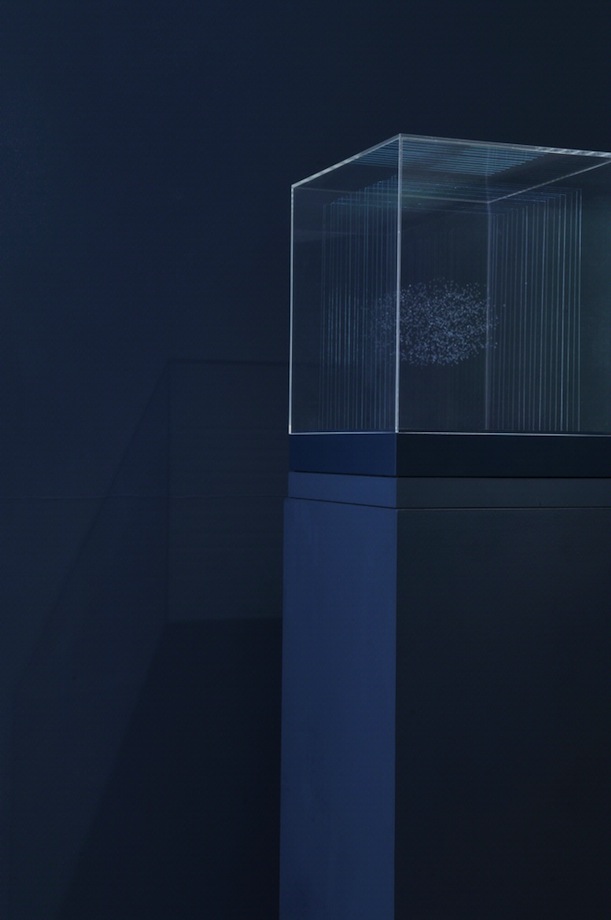

Angela Palmer’s sculpture “Searching for Goldilocks” depicts all of the stars with possible planets that the Kepler Observatory has found. The opaque circles represent stars with “Goldilocks planets,” which are planets that are not too hot and not too cold, but just right for sustaining life. Photo courtesy of Eric Long

Scottish born artist Angela Palmer found inspiration for her artwork in an unlikely place—the Museum of the History of Science in Oxford, England. When she laid eyes on a model built in the 1940s of the structure of penicillin made by Nobel Prize winner Dorothy Hodgkin, Palmer saw more than a relic symbolizing the potential to save millions of people. She also saw the potential for art.

The three-dimensional penicillin model was made with parallel horizontal pieces of glass depicting the contours of electron density and individual atoms. The result is a magnified visualization of the structure that Hodgkin discovered using X-ray crystallography, a method in which beams of X-rays are aimed at crystals, which are then reflected onto photographic plates. The spots that appear on the plates map the 3D structure of compounds.

“When I saw this,” Palmer says, “I thought that if I could turn that model on a vertical plane and take slices of the human head, I wonder if you could, therefore, in three dimensions show the inner architecture of the head.”

So began Palmer’s curious experiments with 3D mapping.

One of her latest installations took a detour from head and body mapping, and she instead looked to the sky for inspiration. The sculpture is a 3D depiction of all of the stars that the Kepler telescope has identified as likely hosts for orbiting planets, and it has a temporary home in an exhibition at the Air and Space Museum. Entitled Searching for Goldilocks, the artwork highlights those planets that have been identified as “Goldilocks planets,” meaning they aren’t too hot or too cold, but just right for sustaining life. The perfect Goldilocks planet against which all the others are measured is Earth itself.

Searching within the Cygnus and Lyra constellations, the Kepler Observatory has found more than 3,000 “candidate planets,” or planets that orbit within a zone that facilitates the formation of liquid water, since it launched in 2009. Of those planets, 46 of them had been identified as Goldilocks planets at the time Palmer created her sculpture.

Each star with planets orbiting in the habitable zone is engraved on one of the 18 sheets of glass in the sculpture. Each star with a confirmed Goldilocks planet is marked by an opaque circle. The space between each sheet of glass represents 250 light years, making the last identified star a mind-blowing 4,300 light years away from Earth.

“It means more than seeing it on a computer screen,” Palmer says. “You can stand and look as if you were the eye of the Kepler telescope and you see the first star that could be hosting a habitable planet, and that’s 132 light years from Earth. Or you can stand behind it and sort of be thrown back through space, back down to Earth from 4,300 light years.”

The engraved stars appear delicate and ethereal floating in the sheets of glass, yet in reality they are massive and far away. Searching for Goldilocks places them in a context that is easier to understand and visualize. “It really shows science in a different light, in a light that you can grasp visually and all encompassing in this little cube,” Carolyn Russo, the curator for the exhibit, says, “and you walk away saying, ‘oh, I get it, I get what the Kepler mission is.’”

From the scientific perspective, the sculpture is an accurate depiction of a 3D chunk of space. And from the artistic perspective, it is an awe-inspiring marvel of floating lights. Palmer blends the two disciplines in much of her work with the goal of appealing to the imagination and presenting facts in a new way. In addition to scanning heads and creating 3D depictions of their inner workings and creating models of constellations, Palmer has also done a myriad of other artistic projects that were inspired by scientific fact. A previous traveling exhibit called Ghost Forest involved placing the dead stumps of giant rainforest trees in city plazas in Western Europe. She came up with this idea after a scientist told her that an area of rainforest about the size of an acre is destroyed every four seconds. Her exhibit was meant to help everyday people visualize the consequences of such destruction.

Although science plays a major role Palmer’s artwork, she is not a scientist. Her background is in journalism, a profession she turned to after dropping out of art school in Edinburgh. After more than a decade in journalism, working for such publications as The Times and ELLE, Palmer returned to art school, enrolling at the Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art in Oxford and channeled her curiosity in a new direction.

“I think curiosity is the secret, isn’t it?” Palmer says. “You can do so much if you’ve just got that curiosity. And I think that’s what the most exciting thing about life really is, if you’re curious it’s just got so many endless fascinations.”

“Searching for Goldilocks” is made up of 18 sheets of glass, each representing 250 light years. Image courtesy of Richard Holttum