The NOW Button Takes Us Back When Women’s Equality Was a Novelty

At the half-century mark, for the National Organization for Women it is still personal—and political

:focal(546x173:547x174)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c1/02/c102d3b1-3efe-4485-a98b-0dcdd474aa0f/nmahrws201402036web.jpg)

In our current moment, stars like Beyoncé, Lena Dunham and Taylor Swift tweet their feminism loud and proud, Facebook’s Sheryl Sandberg urges women to “lean in,” and Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s TED talk “Why We Should All Be Feminists” has been viewed 2.9 million times. Which makes it hard to believe that not all that long ago a woman needed a man to get a credit card, emplorers advertised for "male" and "female" jobs, and the only way for a woman to end an unwanted pregnancy was via an illegal, often dangerous back-alley abortion.

All you have to do is teleport yourself back to the United States in the 1960s, and presto, you’d be in an era in which sexual harassment, date rape and pay equity were not recognized concepts. Laws, rights, terms and ideas that American women take for granted today simply did not exist.

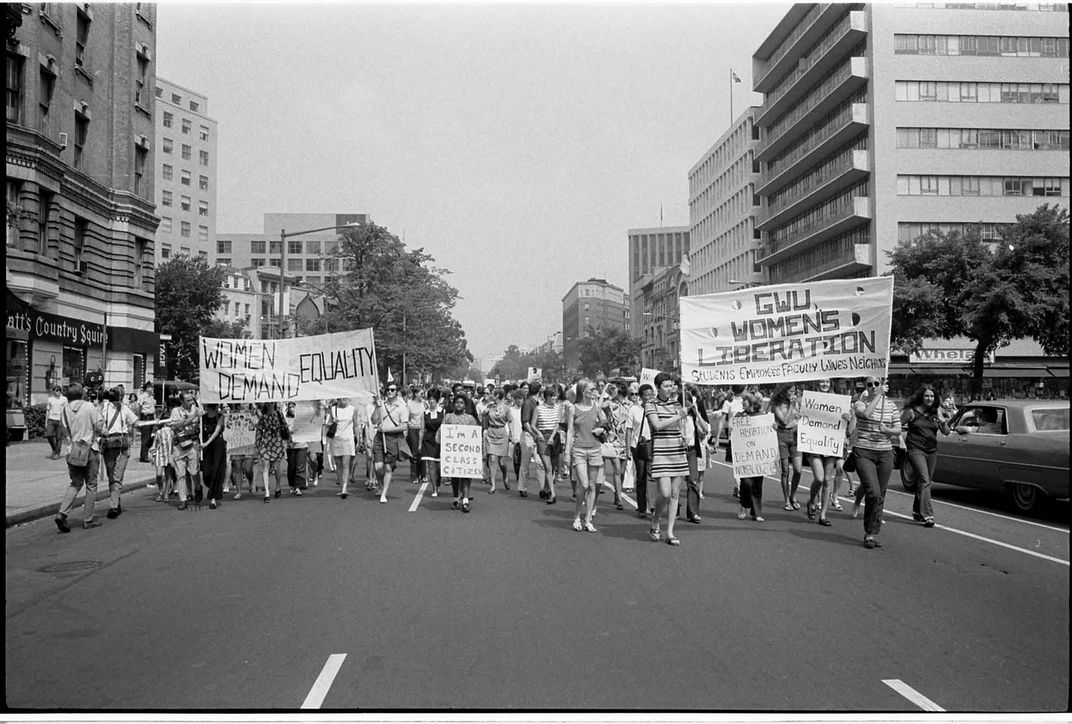

Then in 1966 came the National Organization for Women (NOW), which played a crucial role in changing women's lives. NOW, celebrating its 50th anniversary this summer, was the public face of the women’s movement, lobbying for legislation and executive orders, organizing lawsuits, pickets and marches attended by thousands, raising consciousness about issues that had up until that time been thought of as merely personal rather than the stuff of politics, leading to one of the great slogans to come out of this social movement, "the personal is political."

The logo of the National Organization for Women (NOW), designed by graphic artist and prominent LGBT activist Ivy Bottini in 1969 and still in use today, is attention grabbing. A historic button (above) is held in the collections of the National Museum of American History.

“Even now, in a world of hashtags, if you want to proclaim something to people on the street, you wear a button,” says the museum's curator, Lisa Kathleen Graddy. “You are saying to the person passing you or behind you: This matters enough to me to put on my lapel. You are publicly proclaiming what you are. And although someone might nod and smile at you, if you are upholding a point of view that is not popular, it could also be a risk.”

“There’s something very clear, very bold, very easy to pick out,” says Graddy. “This button works well on that level. I like that the graphic is rounded—which is traditionally [seen as] feminine. It has the idea of wrapping your arms around something. It reminds me of standing on tiptoes and reaching up, reaching toward something.”

Once the personal began to merge with the political, change came fast: In 1967, President Lyndon B. Johnson expanded affirmative action to include women. Starting in 1968, help-wanted employment ads could no longer categorize jobs as being for men or for women. In 1968, the landmark Equal Credit Opportunity Act was passed, freeing women from the requirement of bringing a man along when they applied for credit.

When it was founded, “NOW’s purpose was to take action, to bring women into full participation in the mainstream of American society,” explains Terry O’Neill, the president of NOW. Women who had come out of the labor movement and the Civil Rights Movement banded together in the basement of a Washington, D.C., office building for the first meeting. The driving force was Betty Friedan, who had written the groundbreaking book The Feminine Mystique in 1963, and saw the need for a political organization for women.

Friedan’s book had pointed out the “problem that has no name,” as she put it, and transformed the lives of a generation of women who read it and promptly went back to school, started looking for jobs, and began seeing their lives, their relationships, and world around them differently. “She was a well-educated housewife who changed the course of American history,” according to Alida Brill, author of Dear Princess Grace, Dear Betty, much of which is about Friedan. “I think the National Organization for Women and Betty Friedan are inextricably linked—for a time, she was the face of feminism for a huge group of women in the country.”

In the aftermath of her book’s great success, Friedan realized that something more formal was needed—an “NAACP for women,” in the words of Muriel Fox, one of the founding members of NOW.

And just as the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) was seen by some as too mainstream, so too NOW has over the years been criticized for not being inclusive enough of the concerns of black women, lesbians, working class and poor women. For many women, Gloria Steinem, a founder of Ms. Magazine, with her iconic aviator glasses, long hair, and journalist's media savvy, represented another, more progressive aspect of the women's movement.

But NOW President O’Neill notes that from its founding platform on, the organization has been aware of the “interconnectedness” of issues affecting all women. As the group looks to its future, it is focusing on the rights of immigrant women, on what O’Neill calls the “sex abuse-to-prison pipeline,” and on reproductive health issues, such as access and insurance coverage. “You don’t see the bishops trying to criminalize vasectomies!” she says.

Susan Faludi, author of Backlash: The Undeclared War Against American Women and a new memoir, In the Darkroom, says that the women’s movement of the 1960s “had all the problems that any rights movement has. There’s always this distinction made between the safe, reformist, one-step-at-a-time women’s movement and the more radical wing that came out of SDS [Students for a Democratic Society]. NOW was much more of a reformist movement.”

But, Faludi says, it’s important to remember “how radical it was to stand up for women’s rights in the early ’60s. NOW cleared the way for the upwelling of feminism.”

For younger activists like Nona Willis Aronowitz, 31, author of Girldrive: Criss-Crossing America, Redefining Feminism and daughter of the incisive feminist writer Ellen Willis, NOW didn’t go far enough. What the organization did was “a matter of inclusion, rather than turning the system upside down. It’s not just that women need a seat at the table. The table needs to be re-set.” But she too gives NOW credit for spreading the word: “What they did really well was translate the message to a mass audience.”

Filmmaker Mary Dore, director of She’s Beautiful When She’s Angry, a riveting 2014 documentary about the 1960s and ’70s women’s movement, emphasizes the relevance of those early days: “Movements start at the bottom up. How did they do it with nothing? When they didn’t have internet, they didn’t have money? It’s so inspiring, when you saw those people marching, you saw the power they had within them.” Her goal in making the film, she says, “was essentially to say: 'This is important.' You can build on their successes and learn from their mistakes. You can get power.”

But lest anyone think all the battles have been won, the 2014 Shriver Report tells us that the average American woman makes only 77 cents for every dollar made by a man, and one out of three women in the U.S. (about 42 million people), live in poverty or are teetering on its edge.

All of which means that NOW’s work is far from done. NOW co-founder Fox, one of the women at that first meeting in the D.C. basement, says: “There’s still a need for a women’s movement. We can’t do it as individuals, each of us working for our own interests. We get much further if we work together. You need a movement, you need politics, you need money, you need fighters. It’s amazing how much we can do. You set your goals high, and then you succeed.”

And that’s as true today as it was when NOW was founded in 1966. Just this past week, news photos showed people demonstrating against proposed new restrictions on abortion in Indiana, and front and center were protesters with signs bearing the distinctive NOW logo, instantly recognizable as the symbol of women’s rights.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Smiling-Anne.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Smiling-Anne.jpg)