This Odd Early Flying Machine Made History but Didn’t Have the Right Stuff

Aerodrome No. 5 had to be launched by catapult on the Potomac River on May 6, 1896, but it flew unpiloted 3,300 feet

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4b/4b/4b4b6bb7-6016-4dc1-be4f-115871ea763b/nasm-a19050001000-nasm2018-10823.jpg)

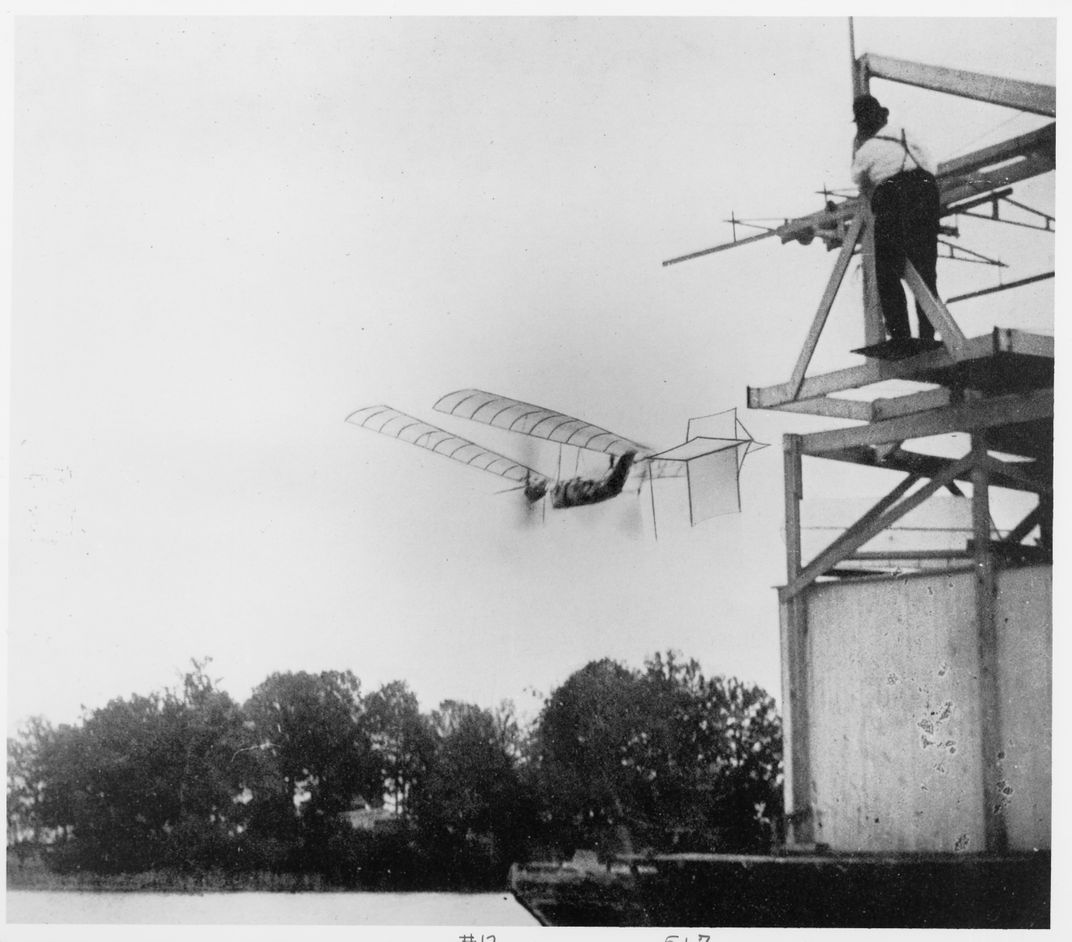

The vessel floated in the shallows of the Potomac River on the leeward side of Chopawamsic Island, just off Quantico, Virginia. At first glance, it could have been mistaken for a houseboat—except for the large scaffold that protruded from the top of the superstructure.

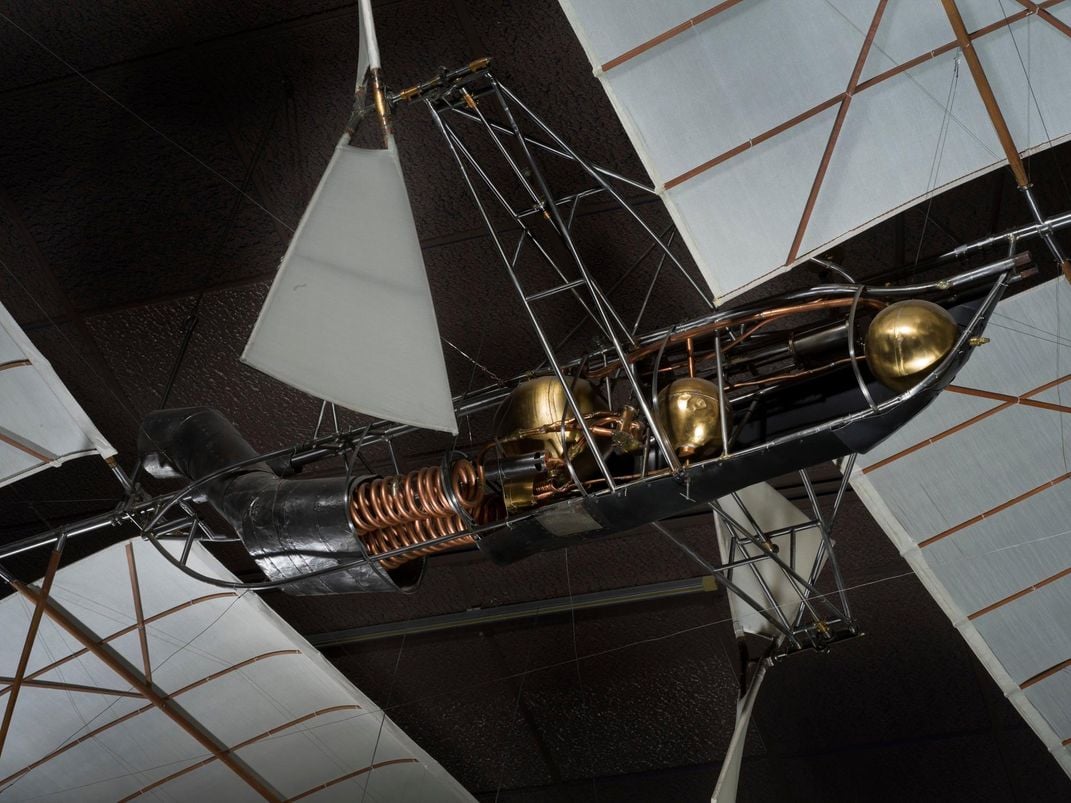

Even more unusual on that calm spring day, 125 years ago, was what was hanging from the formidable framework—a 13-foot-long apparatus made of wood and metal tubing that had two sets of long silk-covered wings forward and aft. Weighing 25 pounds, the contraption also included a small steam-powered engine and two fabric-covered propellers.

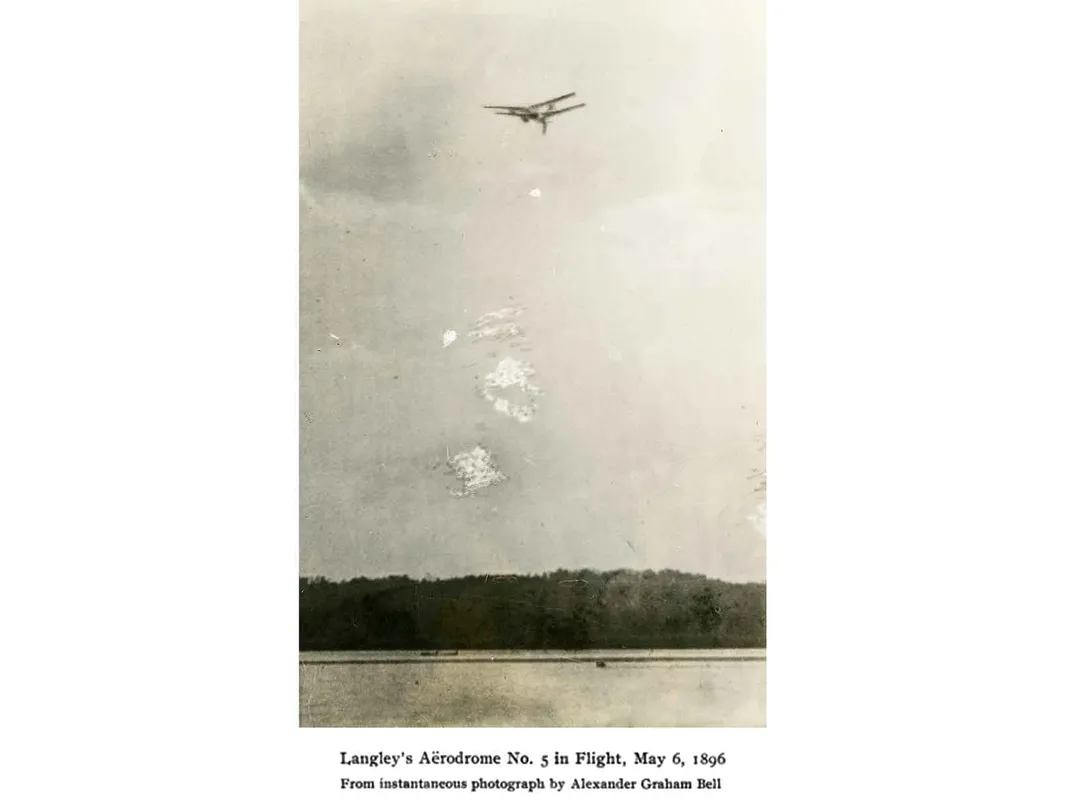

History would be made that day, May 6, 1896, as this apparatus—a flying machine, known as Aerodrome No. 5—was started and then launched from a spring-loaded catapult. The Aerodrome would take off and travel for 90 seconds some 3,300 feet in an effortless spiral trajectory and then gently land in the river.

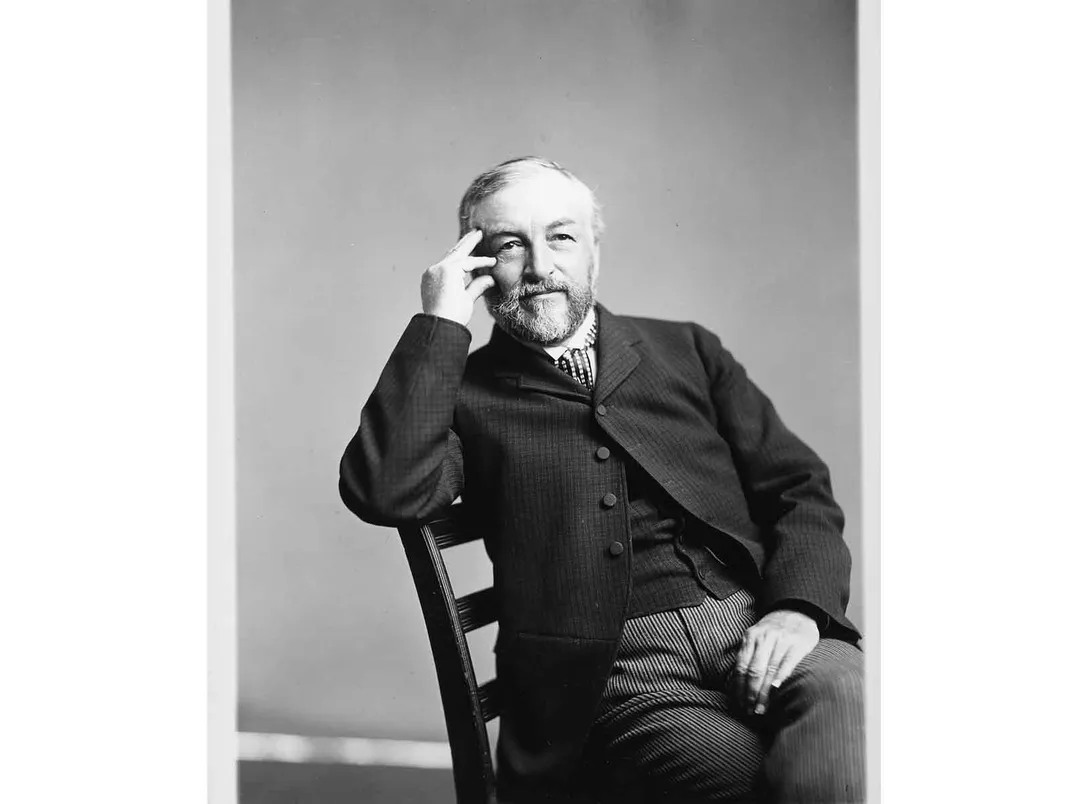

The third Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, Samuel Pierpont Langley, an astronomer who also enjoyed tinkering with his own creations, was aboard the boat. His winged invention had just made the world’s first successful flight of an unpiloted, engine-driven, heavier-than-air craft of substantial size.

With Langley that day, was his friend Alexander Graham Bell, the inventor of the telephone, who watched in amazement. Bell later wrote about how Aerodrome No. 5, now held in the collections of the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., moved with “remarkable steadiness” while in the air. Bell’s account describes the historic moment:

… and subsequently swinging around in large curves of, perhaps, a hundred yards in diameter and continually ascending until its steam was exhausted, when at a lapse of about a minute and a half, and at a height which I judge to be between 80 and 100 feet in the air, the wheels ceased turning, and the machine, deprived of the aid of its propellers, to my surprise did not fall but settled down so softly and gently that it touched the water without the least shock, and was in fact immediately ready for another trial.

The world rightly remembers that in 1903 the Wright brothers achieved human flight at Kitty Hawk in North Carolina. “Langley’s Aerodrome No. 5 wasn’t practical and it wasn’t a working prototype for any real flying machine,” says Peter Jakab, senior curator at the museum. But the largely forgotten unpiloted flight that took place seven years before Kitty Hawk did move motorized flight from the drawing board into reality.

Langley was a renowned physicist, who founded the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, today located in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He built a telescope and recorded exact movements of extraterrestrial bodies to create a precise time standard, including time zones. Known as the Allegheny Time System, this development established the correct time, which was sent twice daily over telegraph wires and allowed trains to run on schedule—a significant problem in the days before standardized timekeeping.

“Langley’s real accomplishments in research were in astronomy,” says Jakab. “He had done a great deal of significant work in sun spots and solar research, some of that while at the Smithsonian.”

Langley also had an abiding curiosity in aviation. He became consumed with the possibility of human flight after attending a lecture in 1886 and began experimenting with a variety of small-scale models. His interest, while serving as Secretary of the Smithsonian—sort of the unofficial chief scientist of the United States at the time—spurred others to further investigate the new field of aeronautics.

“This was still a period when people didn’t think flight was possible,” Jakab says. “If you were a young person in the 1890s contemplating a career in engineering, flight was not exactly an area you would go into. It wasn’t taken seriously by a lot of people. The fact that someone like Langley was starting to study flight gave the field credibility.”

Langley had some success with small model aircraft, and conducted aerodynamic research with a large whirling arm apparatus he designed. He increased the size of his prototypes and began to develop small engines to power them. His first attempts at unpiloted powered flight failed.

After Aerodrome No. 5 completed its two successful flights, Langley began to boast he would be the first to accomplish human powered flight. He repeated the success six months later with a newer improved Aerodrome No. 6.

However, Langley’s designs were inherently flawed. While he had made limited strides in the understanding of lift, thrust and drag, he failed to see that his models when scaled up to include a human and larger engine were structurally and aerodynamically unsound, and were not capable of flight.

“Langley had this fundamentally flawed notion about the relationship between aerodynamics and power,” Jakab says. “He came up with the Langley Law, which basically said the faster you flew, the less drag there was. He believed the faster you would go, the less power you would need. As strange as that sounds to us today, that’s what his data seemed to be telling him then.”

The Smithsonian secretary also did not realize he needed a better control system for a pilot to guide the aircraft in flight. The tail only moved vertically, which provided minimal pitch, while the rudder was located in the center of the fuselage, which offered little aerodynamic effect. Langley also miscalculated the stress factors of building a much larger plane.

“He didn’t grasp that the flight loads on the structure increase exponentially as you increase the size of the craft,” Jakab says. “To build a full-size aircraft, Langley simply scaled up the smaller models. If you tried to use that same structural design for something four times the size, it was not going to sustain itself—and that’s exactly what happened.”

Langley began building larger prototypes in preparation for test flights. The U.S. Department of War took an interest and provided $50,000 in grants to fund the project. Langley also found a young scientist, Charles M. Manley, who was more than willing to pilot the craft on what they hoped would be the first flight.

On October 7, 1903, the full-scale aircraft, called the Great Aerodrome, was loaded on the houseboat on the Potomac River, not far from what is now Marine Corps Air Facility Quantico, and made ready for takeoff. With news reporters watching and photographers making pictures, the Great Aerodrome was launched—and then, it promptly collapsed upon itself and fell into the water. A second attempt on December 8 produced the same results. Less than 10 days later, the Wright brothers would fly into history with Orville at the controls while Wilbur steadied the Wright Flyer as it began its takeoff run.

As might be expected, Langley was humiliated by the press for his failures in flight. That defeat, along with an embezzling scandal by Smithsonian accountant William Karr, left him deeply distraught.

“Those two catastrophic failures in 1903 ended Langley’s aeronautical work,” Jakab says. “He was a broken man because he took a lot of ridicule. He spent a lot of money and did not achieve a great deal in this field.”

Langley died in 1906 at the age of 71. Jakab believes Langley should be remembered for what he accomplished in 1896. His successes with Aerodrome No. 5 and Aerodrome No. 6 are significant and worthy of recognition today. In fact, the Smithsonian Institution once honored May 6 as Langley Day.

“It used to be an unofficial holiday and employees would get the day off,” Jakab says with a hint of mischief in his voice. “I’ve always advocated that we should reinstitute Langley Day and have May 6 off, but the administration has not taken me up on that so far.”

Langley’s Aerodrome No. 5 will be on view in the “Early Flight” gallery at the National Air and Space Museum, currently undergoing a major renovation. The museum is slated to reopen in the fall of 2022.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/dave.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/dave.png)