The Navajo Nation Treaty of 1868 Lives On at the American Indian Museum

Marking a 150-year anniversary and a promise kept to return the people to their ancestral home

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/27/96/2796a3af-7f51-4aad-ac43-6f89686c7f2c/nmai-0010.jpg)

The Navajo Nation is the largest, acreage-wise, and most numerous, of the 500 or so Indian tribes that once roamed the land now known as the United States. That is not by accident. The Navajo people have their ancestors to thank for having stood up to the federal government 150 years ago to demand that they be returned to their homeland.

At the time, in 1868, the Navajo would have appeared to have had little negotiating leverage. They had been marched off their territory by the U.S. Army and held captive in what is now eastern New Mexico for some five years in conditions that could only be described as concentration camp-like. But Navajo leaders were finally able to convince federal officials—chiefly General William Tecumseh Sherman—that they should be allowed to go home.

The acceptance by those federal officials was codified into the Navajo Nation Treaty of 1868 and set the Navajo (known as the Dine) apart from other tribes that were forcefully and permanently removed from their ancestral territory.

“We’ve been told for centuries that we need to always live within the four sacred mountains,” says Navajo Nation President Russell Begaye, who credits the treaty with having rebuilt the nation to some 350,000 Dine people today—up from about 10,000 in 1868.The Dine were one with the canyons, the desert, the rocks and the air in that land that sits between Blanca Peak in the east, Mount Taylor in the south, the San Francisco Peaks in the west and Mount Hesperus in the north, he says.

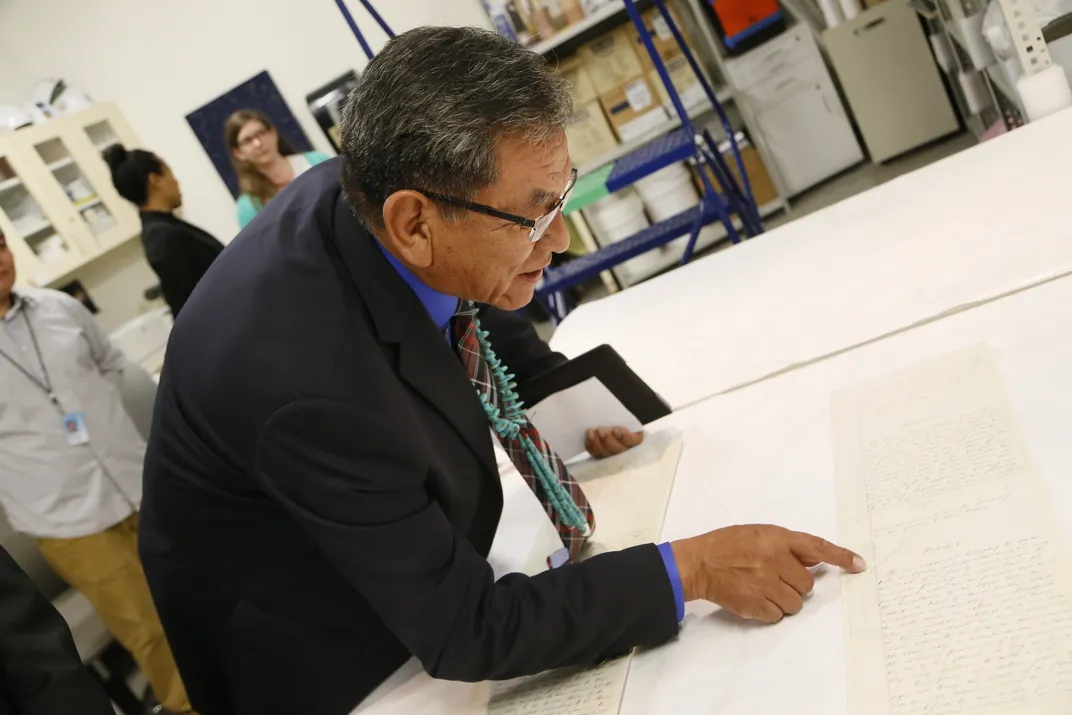

The 1868 treaty, called the “Old Paper,” or Naal Tsoos Sani in Dine Bizaad, the Navajo language, has just gone on display at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. It will remain there until late May, when it travels to the Navajo Nation Museum in Window Rock, Arizona. The treaty’s homecoming is a nod to the momentous return of the tribe in 1868.

At the unveiling in Washington, almost a hundred Navajo people crowded around the dimly-lit glass box that held the treaty, which is on loan from the National Archives and Records Administration.

Elmer Begaye, an assistant to President Russell Begaye, stood to give a blessing. He spoke almost entirely in the Diné Bizaad language, and then offered up a song, which he later said was a traditional song of protection. The tribe’s medicine people advised him to use the protection song, he says, adding that it helps breathe life into the document and allows it to be used for the tribe’s purposes.

“It’s just a piece of paper,” he says. But, he adds, “We use that treaty to be acknowledged, to be respected, and to be heard.”

President Begaye agrees. “It’s not just a historical relic. It’s a living document,” he says, adding, “it’s a contractual agreement with the U.S. government and the Navajo nation.”

Tribe faced annihilation

Like many tribal treaties, the Navajo treaty was secured at great expense.

The Dine had long dealt with Mexican and Spanish incursions, and had navigated their way through the troubled waters of attempted colonization. But the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ended the Mexican War, gave rise to a new threat—American invaders, who claimed the southwest as theirs, according to Navajo historian and University of New Mexico associate professor Jennifer Nez Denetdale.

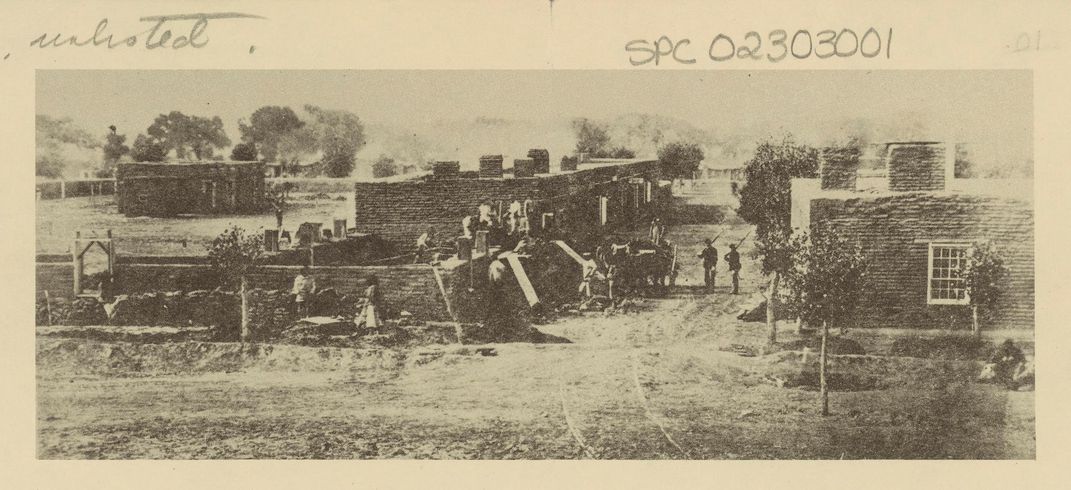

Indian tribes were seen as an obstacle to manifest destiny-driven land grabs. By 1851, the Americans had established Fort Defiance smack in the middle of Navajo country. Not surprisingly, conflicts frequently arose. Major General James H. Carleton, who at the time was the commander of the department of New Mexico, ordered famed frontiersman Kit Carson to put down Indian resistance.

Ultimately, this led to the surrender of thousands of Navajo starting in late 1863, according to Denetdale. From that time until 1866, more than 10,000 Navajo were marched east—in the Long Walk—over several routes to Fort Sumner, also known as the Bosque Redondo reservation. There, the Navajo lived in squalid conditions. Many died of starvation and disease.

“We were at almost a point of total annihilation,” says Jonathan Nez, vice president of the Navajo nation.

The federal government’s initial stated goal had been to assimilate the Navajo, through new schooling and by teaching them how to farm. But they were primarily a pastoral peoples and could not adapt their farming methods to the resource-poor area around Bosque Redondo. In 1865, aware that conditions were deteriorating there and elsewhere in the West, Congress authorized a special committee, led by Wisconsin Senator James Doolittle, to investigate the conditions of various tribes.

The committee met with Navajo leaders and were taken aback at the atrocious conditions. It reported back to Congress, which debated at length over what to do. But the Doolittle committee’s 1867 report—along with the ever-escalating costs of warring against the Indians—persuaded President Andrew Johnson to attempt peace with the various tribes. He sent General William T. Sherman and Colonel Samuel F. Tappan to Fort Sumner to negotiate a treaty with the Navajo, who were led by Chief Barboncito.

In exchange for a return to their homeland—which the Navajo insisted upon—and an allotment of seeds, cattle, tools and other materials, the tribe agreed to allow compulsory schooling of children aged 6 to 16; to not interfere with construction of railroads through the new reservation; and, to not harm any wagon trains or cattle passing through their lands. They began their reverse migration home in June of 1868.

The signing of the 1868 treaty is celebrated every year on June 1. This year to honor the 150th anniversary, the treaty will travel to the Navajo Nation Museum in Window Rock, Arizona, following its display in Washington, D.C.

Denetdale says that stories about the Long Walk are still a huge part of the fabric of the Navajo nation. She has collected many oral histories, including from those who say women were key to convincing both their tribal leaders and Sherman—who had been sent as a peace commissioner—to allow the return to the homeland.

The stories “are very vivid, very stark, and continue to be a part of not just individual or clan, but to be a part of our collective memory,” says Denetdale. The experience “still shapes and informs the present in both positive and negative ways,” she says.

By honoring the treaty “we also remember the struggles of our ancestors and we honor them for their persistence and their perseverance. They had a lot of courage,” she says.

But something is still missing. “The U.S. has yet to give an apology for its treatment of Navajo people,” says Denetdale.

Sovereignty challenges abound, Bears Ears is the latest

The treaty is acknowledged as the key to preserving the tribe’s sovereignty, but it comes with strings, says Begaye. Navajo who want to build a house or start a business on their own land need permission from the federal government, he says. And, “to this day we don’t have control over our natural resources,” says Begaye.

To him, the treaty’s strictures feel almost like the incarceration at Fort Sumner all over again. “All of that is the government holding us in captivity, to keep us in poverty,” he says.

The Navajo people have had to continue to fight to maintain their land—which now spreads out over about 27,000 square miles in the Four Corners area of New Mexico, Arizona and Utah. The treaty promised land in Colorado, but it was never delivered, says Begaye. His administration recently successfully purchased about 30,000 acres in Colorado that will aid Navajo beef operations.

Meanwhile, the Trump administration plans to scale back Navajo sacred lands in Utah at the Bears Ears National Monument. The Navajo people have lived and hunted in the area for centuries, says Begaye. President Barack Obama’s administration established Bears Ears in 2016 as a 1.35-million-acre national monument. President Trump has proposed to cut the acreage by almost 90 percent. The Navajo, along with the Hopi Tribe, the Southern Ute Indian Tribe, the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe and the Pueblo of Zuni, have sued to block that action.

Both Begaye and Vice President Nez hope that young Navajo will be inspired to fight such modern-day incursions by viewing the 1868 treaty. The Navajo are also fighting demons at home, says Nez, listing diabetes, heart disease, suicide, domestic violence, alcoholism and drug addiction.

The old ways of living—evinced in the wherewithal to insist on a return to the homeland—need to be brought into the 21st century “to fight off these modern-day monsters that are plaguing our people,” Nez says. “I see 2018 being a great year of showing pride in who we are as Navajo,” says Nez. “We are a strong and resilient nation and we need to continue to tell our young people that.”

“A lot of our people are hurting,” he says. “A lot of them just need a little dose of hope,” which he says the treaty can provide.

The Navajo Nation Treaty is on view through May 2018, in the exhibition “Nation to Nation: Treaties between the United States and American Nations” at the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)