Olympian Babe Didrikson Cleared the Same Hurdles Women Athletes Face Today

The star track and field athlete of the 1930s boisterously challenged gender expectations with her record-setting athleticism

:focal(777x213:778x214)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/73/8a/738af412-db1e-4278-a7d7-df395838b142/untitled-5.jpg)

Women athletes have always had to clear high bars in order to be taken seriously. In the 1932 Olympic Games at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, Babe Didrikson’s bar was set at 5’5-and-a-quarter inches. That was what she would need to clear in her competition against fellow American athlete Jean Shiley for the gold medal.

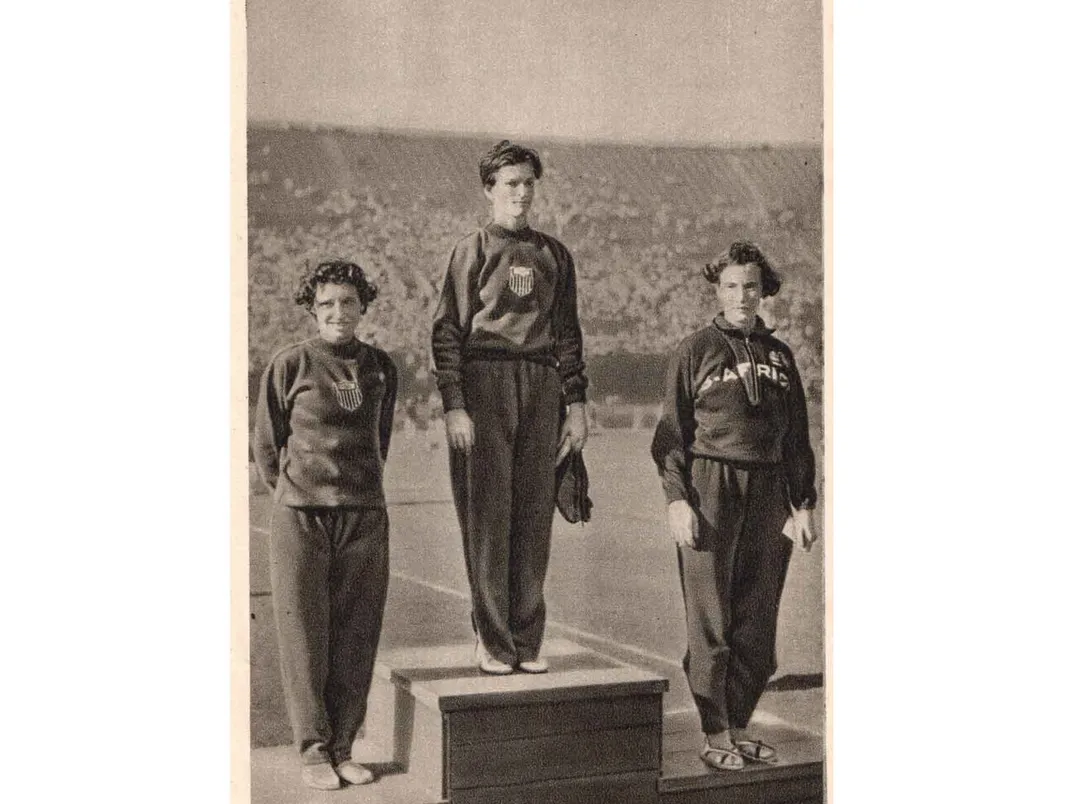

The crowd held its breath as the “Texas Tomboy” ran for her build-up. Didrikson was gunning for a clean sweep, having won gold medals in her previous two events—the javelin throw and the 80-meter hurdles. She launched herself over the bar, and cleared it, setting a new world record as did Shiley. But Didrikson’s technique, officials determined, violated regulations. Though Didrikson argued that it was the same jump style she had used throughout the competition, the gold medal was ultimately awarded to Shiley. Still, the decorated athlete made her mark on sports history.

“Babe Didrikson is the greatest female athlete, in my opinion, of the 20th century,” says scholar Lindsay Parks Pieper of the University of Lynchburg, who has studied and written about the record-breaking athlete.

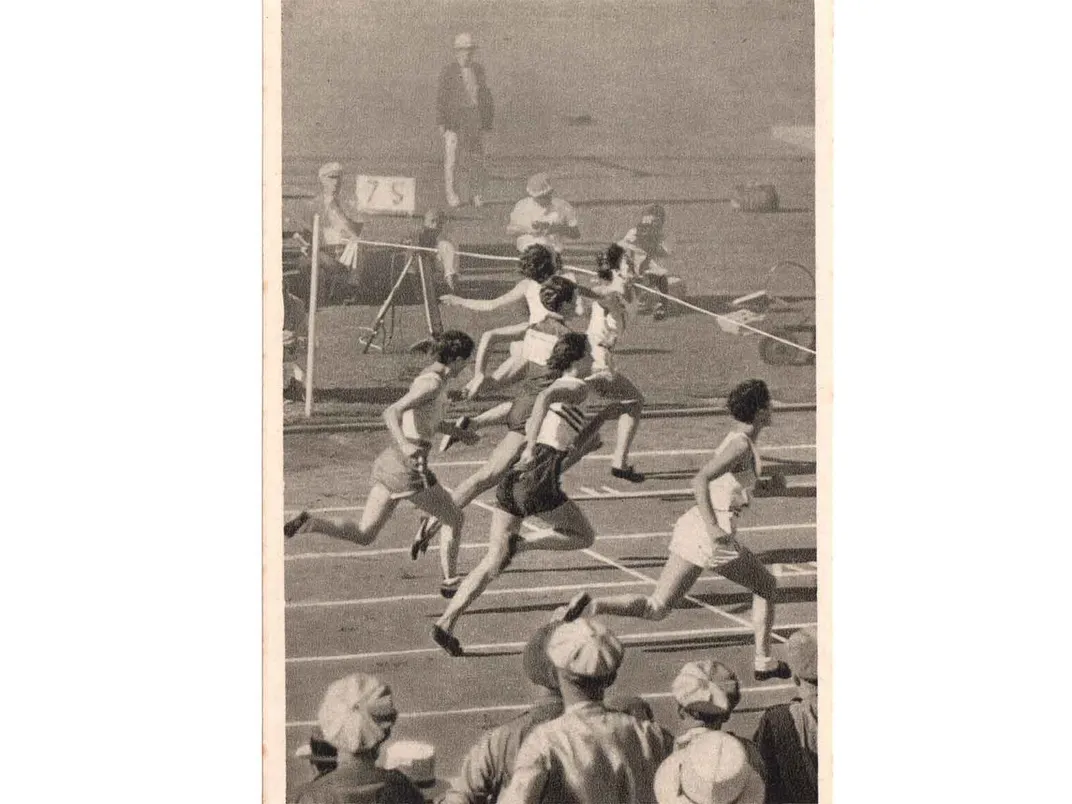

The faces of Shiley, Didrikson and Eva Dawes—the gold, silver and bronze high jump medalists from 1932—glow with the joy of the games in a picture postcard recently uncovered among newspaper clippings in the Archives Center at the National Museum of American History. The artifact was “what we call ‘found in the collection,’” says Jane Rogers, a sports curator at the museum. Rogers was inventorying the archive’s paper materials when she recovered a cache of postcards. In the others, Didrikson can be seen leaping a hurdle, pushing past the finish line and receiving a gold medal for the 80-meter hurdle.

The 1932 Games, marred by the ongoing Great Depression, are not without parallel to the issues facing today’s Olympians in the upcoming games in Tokyo, where athletes are contending with a host of issues related to the ongoing pandemic. Questions that surrounded Didrikson’s gender and sexuality resonate today, too, as women athletes encounter strict scrutiny thanks to the new hormone regulations recently put in place.

Mildred Ella Didrikson was born in Port Arthur, Texas, to Norwegian immigrant parents. Her mother’s affectionate nickname for her, “Bebe,” eventually transformed into her famous moniker Babe—though the athlete claimed that she acquired it after hitting home runs like Babe Ruth in her childhood baseball games. "The Texas Tornado," “Whatta gal Didrikson” and “Texas Tomboy,” as she was later dubbed by the press, was quick with a story of her athletic prowess—a trait that was often characterized as self-promotion and arrogance.

Didrickson was, according to Pieper, “very colorful in her commentary, very boisterous, overzealous, and she knew that she was good.” Everything about her demeanor contradicted expectations for women athletes of the era, and Didrikson complicated what it meant to be a “gal” athlete. “She would show up and say, you know, who's going to come in second today, Babe is here!” Didrikson biographer Don Van Natta Jr. told NPR in 2011.

The track and field star’s prowess in her chosen sports propelled her to the 1932 Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) championships, where she qualified for the Olympics in three different events (80m hurdles, high jump, and javelin). Of course, Didrikson claimed she could have competed in more events, but women athletes were limited to three.

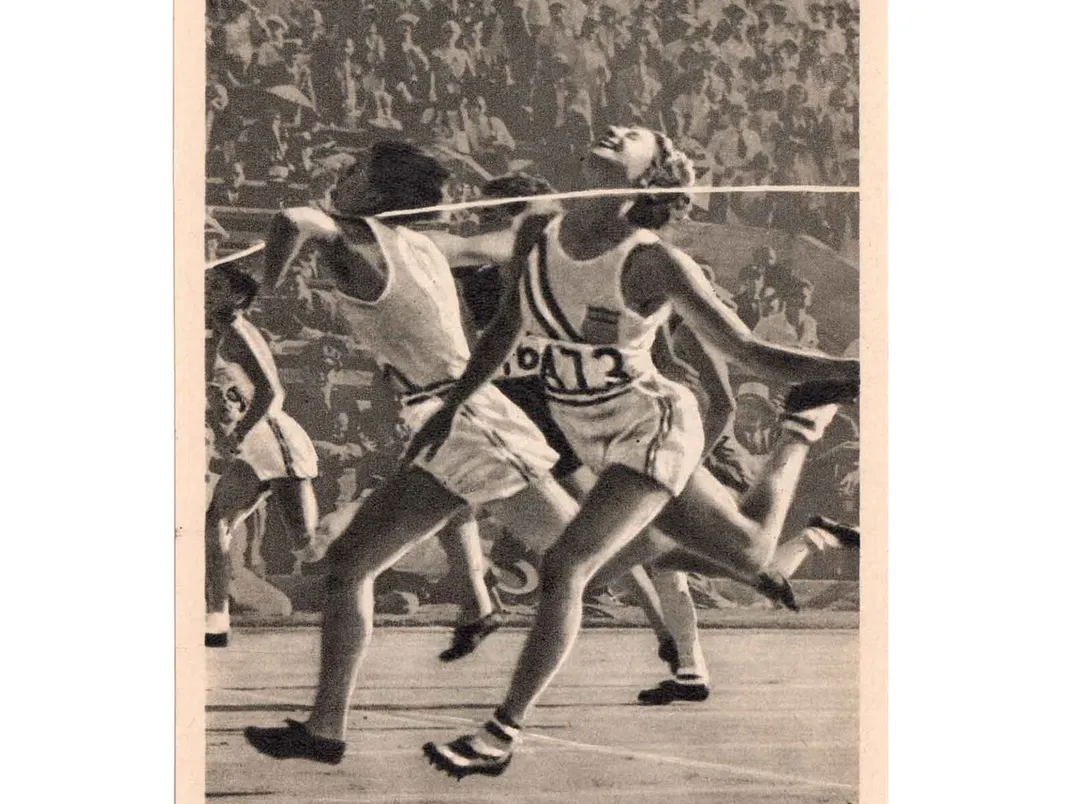

One of the postcards recovered by Rogers depicts Didrikson and Evelyne Hall’s photo-finish at the 80-meter hurdles. The runners can be seen side-by-side as they sped around the track and tore the ribbon in tandem. The dynamic moment captured in the photograph shows Didrikson elbowing past the ribbon while her competitor celebrates the tie. While their racing was extremely similar, their reactions after crossing the finish line diverged.

“Babe Didrikson is celebrating and saying, ‘I’m number one,'” says Pieper. The judges broke into a 30-minute debate to decide the winners. Didrikson’s athleticism certainly carried her across the finish line, but her confidence cemented her win, and she was awarded the gold. Both women set world records with their 11.7-second sprint.

Hall ultimately claimed she lost the gold medal only because she was more reserved than Didrikson. In sports, as in broader society at the time, there was “a certain sense of what respectable womanhood looked like,” explains Pieper of Hall’s reticent demeanor.

Still, despite being a gold medalist, Didrickson was widely criticized for not fitting the “respectable womanhood” archetype. Pieper notes the harsh rhetoric she faced in the media, with the press labeling her “muscle moll” and suggesting she was a member of “the Third Sex.” Didrickson’s brash behavior along with her decorated athleticism challenged every imagined ideal for a woman athlete in the 1930s, when rigid gender categorization and expectations for women athletes mirrored broader societal stereotypes for women. “It's almost as if, through the lens of sports, you can see society in that era,” Rogers notes.

The media treatment Didrikson received in 1932 carries an echo for today‘s world athletics. The governing body for the Olympic Games introduced regulations on testosterone levels for female athletes in Tokyo. This rule has already excluded two teenage sprinters from Namibia. The move has been widely critiqued for disproportionately affecting Black women, as well as intersex and trans individuals.

“The policies that have been enacted claim to be more inclusive but have actually put parameters on ‘men’ and ‘women’ as categories more concretely,” says Pieper. In the context of Didrikson’s experience, she says that “I would argue that women [today] who do not uphold conventional femininity are still treated with this same derision, suspicion and cruelty that Babe Didrikson was facing in the 30s.”

After the 1932 Games, Didrikson went on to become a star baseball player and golfer, marrying the wrestler and sports promoter George Zaharias in 1938. She spent the last few years of her life advocating for cancer research funding after her colon cancer diagnosis in 1953. The gold medalist and lifelong athlete died of the disease on September 27, 1956.

Didrikson’s athletic career, and others’ reaction to it, may remind Olympic participants and viewers in 2021 of the strict expectations women athletes have always been subject to, whether in the form of official regulations or societal pressures. Despite the media rumors and speculation that surrounded her, Didrikson should be remembered as an incredible, multitalented athlete, say those who study and write about her.

“Whenever I asked my students about Babe Didrikson, they rarely know who she is, which is always a frustration,” says Pieper. “I don't think she gets as much historical attention as she should.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/graciephoto.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/graciephoto.jpg)