On the Eve of his Death, Robert Kennedy Was a Whirlwind of Empathy and Internal Strife

These unconventional portraits capture the man’s evolution from straitlaced politician to champion of the poor

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ae/5a/ae5a9337-77c1-4ffd-ad5b-755ba9f64aec/npg_89_tc12-rfk-r.jpg)

Driven by a peacemaker’s passion and righteous urgency, presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy emerges as a red-hot rebel in a Roy Lichtenstein pop art print. Time commissioned it as a cover image for May 24, 1968, just two weeks before Kennedy was killed in Los Angeles.

In his graphic print, now on display at the Smithsonian's National Portrait Gallery to mark the 50th anniversary of Kennedy’s assassination, Lichtenstein produced a fierce facsimile of a man with a message. Using bright colors, Lichtenstein represents the emotional force of a fighter pushing himself to the limit as he nears the final primaries of his campaign. To capture the frenzy of Kennedy’s campaign and his zeal for change, Lichtenstein gives him the look of a superhero ready for battle.

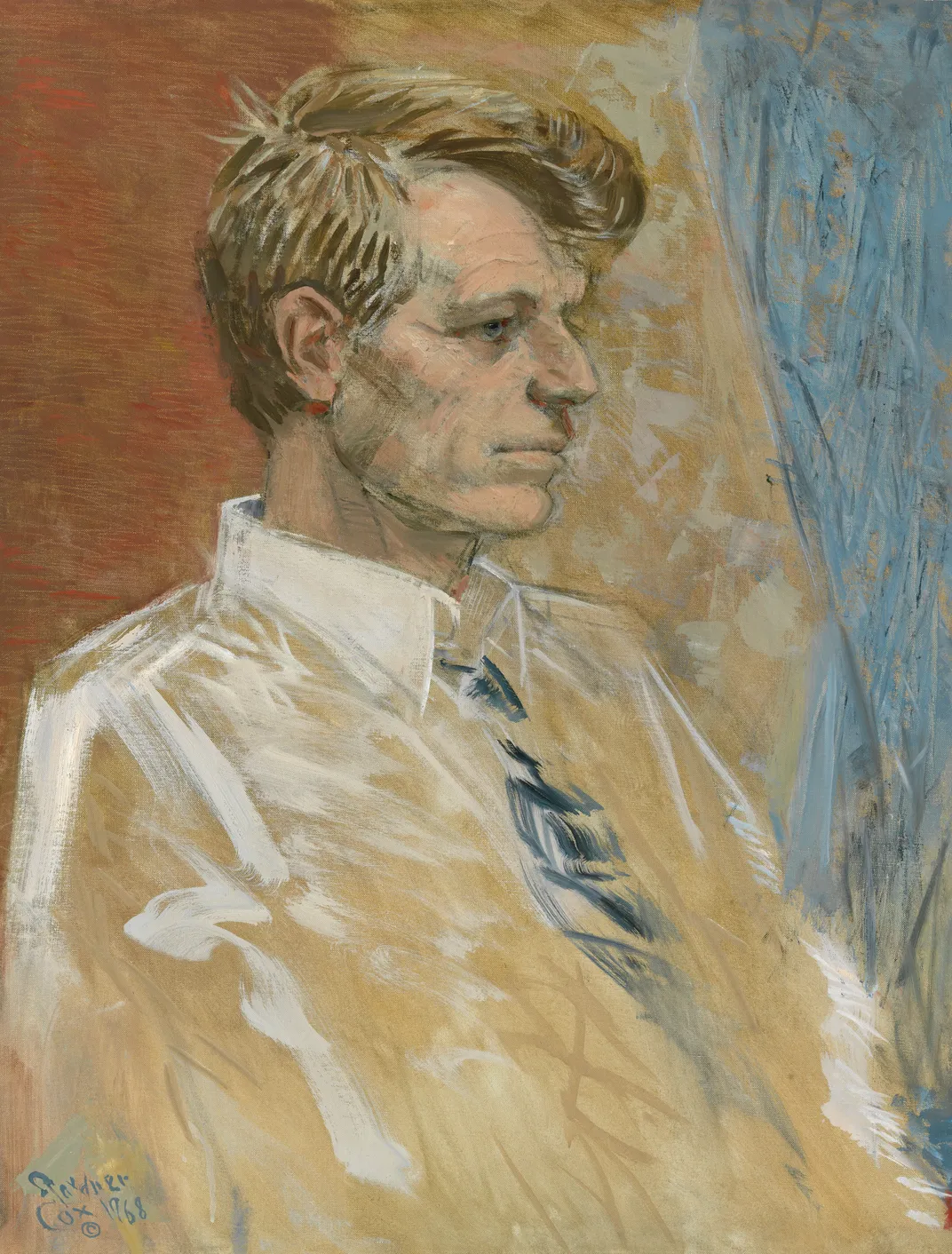

Another 1968 portrait by Gardner Cox, also on view at the museum, depicts RFK sitting, somber, a man buried in thought. His tie loosened, his eyes filled with determination, he wears none of the polish associated with his brother, President John F. Kennedy. In this image, RFK is neither his dapper brother’s ghost nor his ostentatious father’s emissary. He is something quite different: a thoughtful man, unworried by the tidiness of his hair or his clothes, unfettered by the social conventions of his upbringing. This is the Robert Kennedy who began reading poetry after his brother’s 1963 assassination and often wove poetic messages into his campaign speeches.

The Robert Kennedy of 1968 was a moving target that artists struggled to capture. The last six months of his life capped off a period of dramatic internal change undergone in the 1960s. When he became his brother’s attorney-general in 1961, neither Kennedy truly comprehended civil rights issues, says Harry Rubenstein, a political history curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. The civil rights movement changed both brothers, he says. They saw “the brutality faced by African-Americans in a very much more personal exposed way than they had encountered themselves; and now, as president and attorney general, they assumed responsibility for how the nation would respond.”

Over time, Robert Kennedy developed relationships with black activists as well as Chicano and Native American leaders. His commitment grew to encompass the poor of all races, whether they lived in a crowded Brooklyn slum, on a South Dakota Indian reservation, or in a lonely Mississippi delta shack.

Many analysts believe JFK’s assassination staggered Robert Kennedy so forcefully that his own vulnerability transformed him into an advocate of the disadvantaged. “This sense of common suffering was a major reason for the strong link between Kennedy and black people, and of their allegiance to him,” argues Ronald Steel, the author of In Love with Night: The American Romance with Robert Kennedy. The youngest Kennedy brother, Senator Edward Kennedy, believed JFK’s death re-directed “Bobby.” In his memoir, “Ted” wrote that his brother’s “fast-blossoming idealism” drove him to “take on issues that championed America’s dispossessed.”

A student of humanity, Robert Kennedy learned and grew as JFK’s presidential campaign manager in 1960, as attorney-general through mid-1964, and as a U.S. senator from 1965 until his death.

One turning point occurred in 1960. Authorities had arrested Martin Luther King Jr. in Atlanta, and JFK called his wife Coretta Scott King. Initially, Robert Kennedy was outraged by a gesture that could repel Southern voters. However, by the end of the day, Robert Kennedy had reconsidered and gone even further, calling a judge to win King’s release.

When he was attorney-general, his understanding grew as he felt compelled to intercede in conflict between activists and segregationist Southerners. At first hesitant, he soon identified with the protesters and deplored the injustices they faced. This change accelerated after he became a senator. Rep. John Lewis, D-GA, recalls that with time, Kennedy “almost became a crusader for civil rights, for social justice.”

As a member of the Senate Subcommittee on Migratory Labor in March 1966, he visited California to better understand a strike by grape pickers. Led by César Chávez and Dolores Huerta, farmworkers sought more rights and hoped to gain leverage by winning public support of grape and wine boycotts. In a Senate hearing, Kennedy listened incredulously as the local sheriff testified that he had arrested strikers not for committing crimes but for appearing “ready to violate the law.” He suggested that the sheriff and district attorney use a lunch break to read the U.S. Constitution.

He quickly developed rapport with Chávez, who advocated peaceful protest among mostly Chicano and Filipino farmworkers. (Their friendship grew so close that in March 1968, Chávez asked Kennedy to join him as he broke a 36-day hunger strike to dramatize the hardships of migrants.) Unlike other politicians, Kennedy asked, “What do you want and how can I help?” says Eduardo Díaz, director of the Smithsonian Latino Center. “He was very much learning through this process, but he was a quick learner.”

Kennedy developed more insight in April 1967 when he accompanied three senators on a fact-finding mission to Mississippi. He was shocked by the hunger he saw. “My God, I didn’t know this kind of thing existed!” he exclaimed. “How can a country like this allow it?” After talking with a child who survived on a diet of only molasses, he wept.

Following that trip, Kennedy wanted to promote a spectacle to humanize the problem of poverty. His impressions contributed to planning for the Poor People’s Campaign in 1968. He encouraged hunger expert Marian Wright to contact King and launch a campaign “because he knew that both she and King, as well as he, would like to bring the issue of poverty to Washington so that lawmakers could see the impact and the effects of poverty for themselves, face-to-face—to see the faces of poverty essentially,” says Aaron Bryant, curator of the exhibition “City of Hope” Resurrection City & the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign,” a show produced by the National Museum of African American History and Culture and on view at the American History Museum. The Poor People’s Campaign built a shantytown on the National Mall, where Americans slept upon the nation’s front lawn for weeks.

Over the years, Kennedy developed a collegial relationship with King and other moderate black leaders. (This happened gradually and despite Attorney-General Kennedy’s then-secret 1963 authorization of FBI wiretaps on King’s phone after allegations about Communists within his inner circle.) In his later years, Kennedy also welcomed sometimes-brutal discussions with African-American radicals, who broadened his understanding of black life in America. One such meeting occurred in Oakland, California, shortly before his death. It was a late-night meeting with Black Panthers and other protestors. Former astronaut John Glenn, who accompanied him, recalled, how the audience hurled “angry accusations about how their community was treated.”

“Bobby’s willingness to listen, and his visible caring,” wrote Glenn in his memoir, “had a way of converting people to his side.”

Kennedy was not afraid to let circumstances change his mind. This made it possible for him to acknowledge a part in Kennedy administration decisions to U.S. military advisers in Vietnam, while opposing Lyndon Johnson’s expanded commitment that sent more than 500,000 Americans to war in 1968.

At the same time, he maintained his positions when facing audiences that might disagree. While he welcomed students who supported his anti-war stand, he told them that he could not endorse draft deferments for college students because these exceptions sent a disproportionately high number of black men to Vietnam, while students enjoyed frat parties and classroom discussions. And despite sympathies toward African-Americans, his belief in law and order made it difficult to accept the riots that scarred U.S. cities in the mid- and late-1960s.

Robert Kennedy was a polarizing figure throughout the 1960s, but this was especially true in 1968, when he joined the Democratic presidential campaign against his old nemesis President Lyndon Johnson and newly popular anti-war candidate Eugene McCarthy. Pro-Kennedy crowds reached so hungrily to touch him that the campaign had to assign a man to hold him in the car during motorcades—and on one occasion, tumultuous supporters pulled RFK out of the car, wrenching the hip of the man holding him. At the other extreme, old party regulars, who ultimately embraced Vice President Hubert Humphrey’s campaign after Johnson left the race, considered him a left-wing opportunist, while many opponents of the Vietnam war saw him as a late-comer trying to exploit McCarthy’s success. Inside and outside the Democratic Party, he had more than his share of critics.

When shots mortally wounded him in June 1968, his wife, Ethel, asked Glenn and his wife, Annie, to escort her children home, and the following day, Glenn guided them into a new life as fatherless children. While he stayed at the family’s Virginia home, Glenn visited Kennedy’s study and found open books with passages underlined. He read them and saw Bobby Kennedy’s life reflected in the writings of Ralph Waldo Emerson: “If there is any period one would desire to be born in, is it not the age of revolution, when the old and new stand side by side and admit of being compared; when the energies of all men are searched by fear and by hope, when the historic glories of the old can be compensated by the rich possibilities of the new era?”

Like Emerson’s words, the portraits by Lichtenstein and Cox offer glimpses of the man in 1968. Lichtenstein’s graphic image took on an eerie feel after Kennedy walked away from microphones to face deadly gunshots, not from a super-villain, but from one very small, very ordinary man.

Cox’s work, begun in February 1968 but not completed until after Kennedy’s assassination, was commissioned by the Department of Justice and now resides in the National Portrait Gallery. Both works of art represent part of Robert Kennedy’s legacy—the beguiling opportunity to imagine different outcomes. Even 50 years after his death, many still see him as a glimmering image—a “what if” who was willing to acknowledge his nation’s faults and imagine a better, more compassionate America.

In his biography/memoir, Robert Kennedy: A Raging Spirit, Chris Matthews suggests that “the endurance of the idea of ‘Bobby’ is, I believe because he stood for the desire to right wrongs that greatly mattered then and which continue to matter every bit as much in the twenty-first century.”

Comparing those days with today’s political environment, Díaz says, “It’s hard to predict just how clearly RFK’s clarion voice would be heard.”

The Roy Lichtenstein portrait is on view at the Smithsonian's National Portrait Gallery June 6 to July 8, 2018; the Gardner Cox portrait can be found in the museum's "20th Century Americans: 1950-1990" exhibition.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)