In 1967, the New York Times reported that a carousel was to be permanently installed on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., adding cryptically that the news “disturbs some people.” Wary of some of the ideas that the Smithsonian secretary S. Dillon Ripley, three years in to the job, had proposed—outdoor puppet and musical performances, sound and light shows, popcorn wagons—arbiters of culture in Washington feared that the Smithsonian Institution would become an “ivy-covered Disneyland.”

But Ripley, recalling boyhood rides on a carousel just outside the Louvre in Paris, faced down his critics and that summer installed a 1922 merry-go-round with 33 gliding animals and two chariots in front of the Arts and Industries Building. Complete with a Wurlitzer band organ, its wooden pipes and bellows blasted “The Sidewalks of New York” and other oompah favorites. Never mind the raised eyebrows of society, Dillon assured his critics that that the carousel was a “living extension of the museums” and indeed, it was an immediate hit with Smithsonian visitors as well as city dwellers, who paid 25 cents each to ride it.

“One of the best things that’s happened,” wrote one district resident in a 1967 letter, as if reassuring Ripley that his decision was a wise one. “I believe I am speaking on behalf of many parents and children, both residents and tourists, when I thank the Smithsonian for erecting the delightful carousel on the Mall.”

In the early 1980s, museum officials replaced Ripley’s worn-out merry-go-round with a larger one, a 1947 vintage model with 60 horses that is now undergoing a major conservation and restoration with a scheduled return to operations in the fall of 2025. Last week, the carousel’s animals, platform and surrounding infrastructure were disassembled and loaded up on trucks destined to Carousels and Carvings, a restoration facility in Marion, Ohio, specializing in the “faithful reproduction of original style parts” and bringing the “grand machines [back to the way] they used to be.” Over the next two years, the restorers will evaluate the carousel’s animals, its platform and its operating infrastructure to make repairs and to ensure safe operation for years to come.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/5e/b5/5eb5b5f3-c5c9-430a-ad06-603d5f5f5f90/img_2305.jpeg)

The carousel arrived in 1981 with a legacy worthy of the historic museum complex surrounding it. Built in 1947, this merry-go-round had operated at Gwynn Oak Amusement Park just outside Baltimore and was the focus for desegregation activists during the civil rights movement. On the same day that Martin Luther King Jr.’s voice rang out at the March on Washington on the National Mall with his “I Have a Dream” speech—August 28, 1963—some 45 miles north of D.C., the whites-only Maryland park became desegregated.

When she was just under a year old, Sharon Langley and her parents became the first Black family to walk through the gates of the park. When her father set her on the back of the colorful carousel horse with its black mane and yellow trimmings, her ride in that moment symbolized the park’s integration, she says.

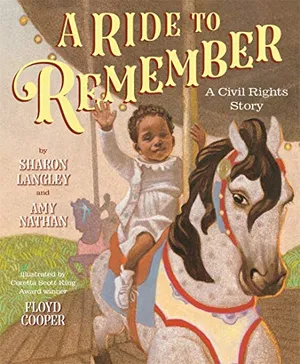

Langley’s delightful 2020 children’s book, A Ride to Remember: A Civil Rights Story, co-written with Amy Nathan and illustrated by Floyd Cooper, recounts how the community’s citizens came together that summer to end segregation in their local amusement park.

Smithsonian magazine caught up with Langley and asked her to share some of her memories of that historic moment when she and her father took a ride on the back of the up-and-down merry-go-round horse, and what it means for her that kids can continue to enjoy the carousel on the National Mall.

The joy of riding a carousel is universal. But the ride your family took was greater and grander. Tell us how the moment continues to resonate?

I was very young, not quite a year old. So, I am thankful for our family’s oral history tradition, which meant that I grew up hearing about our day at the park with the understanding that we’d contributed to something very meaningful.

I often reflect on and refer to Dr. King’s writing, particularly “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” These were the memories of Black families’ experiences at the time:

When you suddenly find your tongue twisted and your speech stammering as you seek to explain to your 6-year-old daughter why she can’t go to the public amusement park that has just been advertised on television, and see tears welling up in her eyes when she is told that Funtown is closed to colored children … then you will understand why we find it difficult to wait.

He remarks on his dreams for his children. … And what does a parent want? To avoid the unpleasant truths of a prejudiced society. To refuse anything that would threaten a child’s freedom to dream and to become. To avoid anything, any experience, condition or person that would warp a child’s warm and accepting nature … a parent’s dreams for his children … to be free from the “clouds of inferiority” that might threaten to form in “her little mental sky.”

What was happening behind the scenes that day in Baltimore? Tell us about the community and the consciousness-gathering that brought change?

In Baltimore in 1963, things were beginning to change because of the efforts of very dedicated activists, clergy and community groups. Thanks to Amy Nathan’s comprehensive research on the history of the integration of Gwynn Oak Amusement Park, we were able to acknowledge and honor them in this book. Floyd Cooper’s exquisite illustrations capture the July protests at the park and the increasing public pressure, leading up to the historic decision to open the park to everyone on August 28 [the same day as the March on Washington].

What should those who fight for civil rights today learn from what your community accomplished in the 1960s?

The convergence of faith and forward momentum is powerful. Faith in a higher, greater good. Faith that our actions and choices can make a difference. Faith that humanity deserves a chance. And the resulting action. Action will meet us there to effect change. If I believe what I say I believe, I will step out in the right direction and with power.

I looked at the young people of Tennessee who walked out of their classrooms last month and formed a multigenerational, multiracial, multi-(fill in the blank) body of people filling the streets in front of the State Capitol standing together, saying together, “We want change.” I have faith that the work continues.

Look around. Open your eyes. We are not alone. Those that are with us are more than those against us.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a4/02/a402328a-7594-4a50-85fb-373df8a1cf64/img_2344.jpeg)

A Ride to Remember: A Civil Rights Story

The true story of how a ride on a carousel made a powerful statement

What else would you like for families to remember when they come to take their rides on the historic carousel when it reopens?

Every person has dreams … dreams for themselves and for the people they love.

When I visit with young people to read from my book, I like to invite them to brainstorm all of the justice virtues and positive attributes they can think of, like fairness, kindness, equality and love. Then I offer them a crown to decorate and to wear with the words “I ride for fairness,” “I ride for kindness,” “I ride for equality,” “I ride for love.”

So when I sign copies, I write: “Let’s ride together,” knowing that we are united in justice, fairness, kindness, equality and love.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(1352x1082:1353x1083)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/45/ae/45ae23b5-636a-4a88-bba7-bdd3bb0f7495/img_2346.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Beth_Head_Shot_High_Res-14-v2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f8/fb/f8fbe968-699c-4142-b844-d444731bf37a/img_2336.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ad/29/ad295eb4-ba94-42f3-816b-38d1251f6efb/img_2294.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/50/ad/50ad38e6-ca83-4b08-b3a4-c9a543e32715/img_2278.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8d/98/8d982ca7-fbf9-4152-9694-e6204d13bddf/img_2267.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/2f/7b/2f7b8d80-3a94-48a6-b3e1-74ac5dc74f3f/img_2233.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/fa/1c/fa1ce2ed-80f6-4ee3-a47e-0adc79b53075/img_2207.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e7/35/e735f7a7-d186-433a-9c59-c259edc849fc/img_2200.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/45/86/45869a9f-c221-470b-92cb-fdeaebd0ec83/img_2163.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Beth_Head_Shot_High_Res-14-v2.png)