In Hawai’i, Young Storytellers Document the Lives of Their Elders

Through a Smithsonian program, students filmed a climactic moment in the protests over the building of a controversial observatory

:focal(942x200:943x201)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/66/41/664155fa-5715-4c19-8235-eea7a067d03f/dsc04139.jpg)

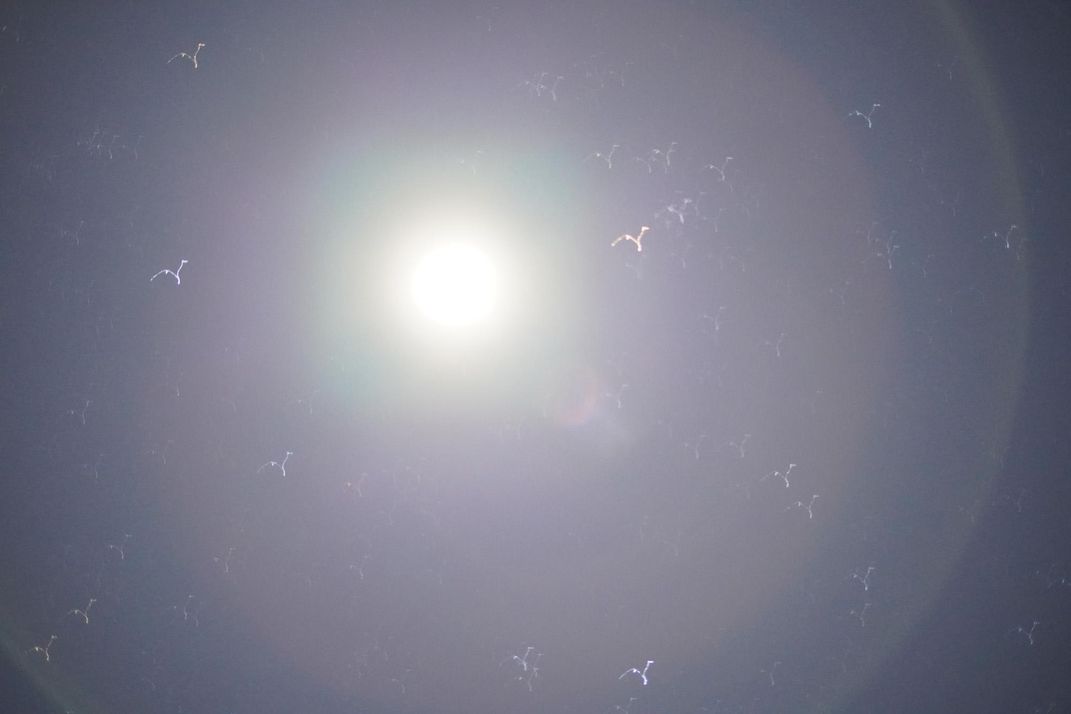

On a cool winter evening in early January, 19-year-old Millie Leong turned her camera to the inky black sky stretching over the peak of Maunakea.

With temperatures hovering around 30 degrees Fahrenheit, the roads of the rain-lashed Hawaiian mountain were glazed with ice. But Leong and her peers—all bundled in thick coats and multiple layers of long-sleeved shirts and socks—paid the cold little mind, turning instead to the stars and clouds peppering the scenery above them. It was Leong’s first time handling a night lens, and she was eager to explore.

“It wasn’t a steady shot. . . but just being able to take the pictures is kind of amazing,” she says. “The blur made the stars look like birds.”

With its 13,803-foot unpolluted peak, Maunakea (the Hawaiʻi Board on Geographic Names recommends the Native Hawaiian single-word spelling, meaning the mountain of Wākea) is considered one of the world’s best spots for stargazing, and the dormant volcano’s summit is the planned future home of a giant observatory called the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT). But the mountain, which already sports 13 other telescopes, is also one of the most sacred sites in Hawaiian cosmology—and many of the state’s community elders, or kūpuna, fear further construction will do irreparable damage.

By January 2020, many of the kūpuna had been camped in protest on the mountain’s frosted flanks for many months, as part of a longstanding campaign to stymie construction at the summit. Just hours after Leong snapped her own shots of the cosmos, Charles Alcock, director of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, met with the elders at Maunakea—the first time since the start of the demonstrations that a representative from the astronomical community visited the encampment to engage in respectful conversation with the mountain’s protectors, or kia’i. An event that brought together two sides of a longstanding debate, it was a crucial moment in the discourse around the hallowed mountain’s fate. And Leong and her peers were there to capture it on film.

Leong and five other students are now graduates of the Our Stories program, a project that equips young Hawaiians with the technological skills to document oral histories from island natives. They spent the second week of January at Maunakea, interviewing the kūpuna while learning the ropes of photography and filmography.

“It was amazing stuff,” says Kālewa Correa, the curator of Hawaiʻi and Pacific America at the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center (APAC) and Our Stories’ project leader. Some of their footage “captures history in the making.”

Though currently on hiatus due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Our Stories, now in its third year, has already archived dozens of stories from community elders across the state, all captured through the eyes and ears of Hawaiʻi’s next generation of creatives. The goal, Correa says, is to create “an army of digital storytellers” who are empowered to catalogue the cultural goings-on in their own backyard—and bolster representation of Hawaiians on both sides of the camera.

In many ways, “you can only tell stories about a community if you’re from the community,” says Conrad Lihilihi, a filmmaker and educator with Our Stories. “If you’re not from Hawaiʻi. . . there are so many nuances people miss. At the end of the day, we must take some kind of authorship of our own stories.”

Correa, who grew up in Hawaiʻi, was inspired to kickstart Our Stories in 2017, after taking part in the development of APAC’s Culture Lab in Honolulu—a series of interactive workshops and performances featuring local artists and scholars. Realizing that the island’s native elders represented a living archive of Hawaiʻi’s past, Correa, who has a background in audio engineering, decided to document their knowledge before it disappeared for good. The best way to do this, he says, was to recruit the help of students—a younger generation already poised to receive this form of cultural inheritance.

The project’s first iteration took the form of a week-long media camp, held in 2018 for a group of freshmen and sophomores from Kanu o ka 'Āina, a public charter school in Waimea. In just a few short days, students learned basic skills in filmmaking, podcasting and visual storytelling—a jam-packed bootcamp Correa describes as “wonderfully awesome, but also completely chaotic.”

Kualapu'u Makahiki Podcast V1

The crash course was so intense that Correa was surprised when one of the younger students, a then-freshman named Solomon Shumate, asked if he’d be able to borrow equipment to create a podcast for his senior year capstone project. In the two years since, Shumate, now a high school junior, has been partnering with Correa to interview farmers around Hawaiʻi on the impacts of pesticide use on their land.

“I really connected with podcasting,” says Shumate, an aspiring performer who was introduced to the technical aspects of audio storytelling through Our Stories. “[The film camp] taught us how to be creative and explore and create our own stories.”

The following year, Correa and his team decided to take a different tack, this time focusing primarily on audio storytelling with a group of first and third graders on the island of Molokaʻi. Sent home with field recorders, the students interviewed the closest elders they had on hand: their own grandparents. Some of the stories included accounts of the island’s annual Makahiki celebrations, commemorating the ancient Hawaiian New Year with traditional games.

“They were all super jazzed,” Correa says of his students. “And all 16 recorders came back to me—I judge that as a success.”

Correa and his team hope the students’ efforts, which highlight the oft-ignored voices of Native Hawaiians, will reach audiences far beyond the island state’s ocean borders. “Our stories are generally told by other people,” he says. In recent years, several filmmakers have received backlash for hiring white actors to play Hawaiian characters. Pacific Islanders also remain underrepresented across multiple forms of media, where white faces and voices have predominated for decades. “But we have our own stories that are important to tell,” Correa says. “The idea is to remind the world that we exist.”

Even within the greater Hawaiian community, these digital documentations can help break down barriers, says Naiʻa Lewis, an artist and podcaster who helped coordinate the efforts on Molokaʻi. “This means someone on Oahu [where certain Makahiki traditions are no longer as widespread]. . . can hear a firsthand account [of the games]. These centuries-old practices. . . can be regained and strengthened in more contemporary ways.”

The next iteration of the oral histories project is planned for American Samoa and the Marshall Islands—something that’s now been delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic. But Correa and his team are still working through footage from past seasons, including clips from the trip to Maunakea, which they hope to compile into a documentary and perhaps eventually submit to a film festival.

In the past few years, Maunakea has become an oft-cited feature of national news. But coverage of the kūpuna, sourced from their own community, inevitably casts a different light on a familiar story—one that is writing young Hawaiians into their own history books.

Part of that narrative involved exposing the Our Stories students to the same conditions the kūpuna—many of whom are in their 70s or 80s—have been weathering on Maunakea for months, if not years, says Sky Bruno, a filmmaker and Our Stories educator who helped supervise the trip. Pristine and unsettled, the mountain has few accommodations. During their trip, the Our Stories team camped in a pair of cabins outfitted with nests of sleeping bags and borrowed sheets. But most of the kūpuna were making do with even less—tents and portable toilets—and holding their ground despite multiple attempts by law enforcement to physically remove them from their posts. (In March, the kūpuna suspended their activities due to the threat of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.)

“On the news, Maunakea looks beautiful and clean,” says Lindsey Wilbur, an Our Stories educator and faculty at Hakipuʻu Academy, a learning center in Kaneohe. “It takes away the reality of what it means to be up there.”

The January excursion wasn’t the first trip to Maunakea for Leong, who by this point had been traveling to the mountain regularly with Calvin Hoe, one of the kūpuna protesting the telescope. But up until this point, Leong had mostly shied away from interacting much with the other elders.

Posted at the volcano’s base for a full week, Leong battled a mild case of altitude sickness—and pushed herself to be a bit braver. “It was eye-opening,” she says. “There were a lot of different arguments of why they shouldn’t build [the telescope]. . . that’s why I feel the kūpuna stayed there for that long. Every time I asked a question. . . [I understood] there’s more than what meets the eye.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/10172852_10152012979290896_320129237_n.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/10172852_10152012979290896_320129237_n.jpg)