The Much-Loved Paddington Bear Turns Sixty

Celebrating the October 1958 publication of A Bear Called Paddington, Smithsonian Libraries takes a look at several pop-up books

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/dc/dd/dcddc5fa-8ed8-42e1-98f3-e42e10e2e268/ap_393212365147.jpg)

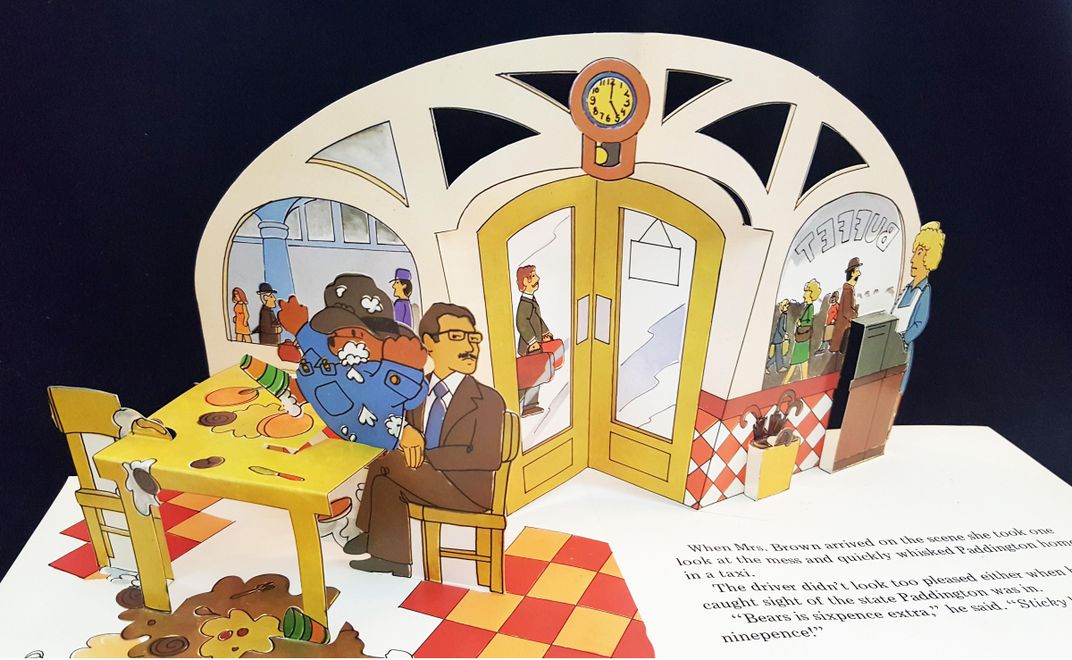

The plot of the much-loved 2017 film, Paddington 2, revolves around a one-of-a-kind, pop-up book. The volume is for sale in the Notting Hill antique store of the Hungarian refugee Mr. Gruber. After opening the covers to the movable parts within, the good-souled, marmalade-loving bear is transported into a dreamlike world of a London cityscape—all of it folding and popping up like the intricate paper constructions of a pop-up book.

The film is based on the children’s books of the late author Michael Bond, who 60 years ago this month, published the first volume, A Bear Called Paddington, on October 13, 1958. There were 15 Paddington titles in all, plus picture and gift books, a cook book and a guide to London. Within the collections of the Cooper-Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum Library in New York City are ten Paddington titles, all in the form of pop-up or sliding books.

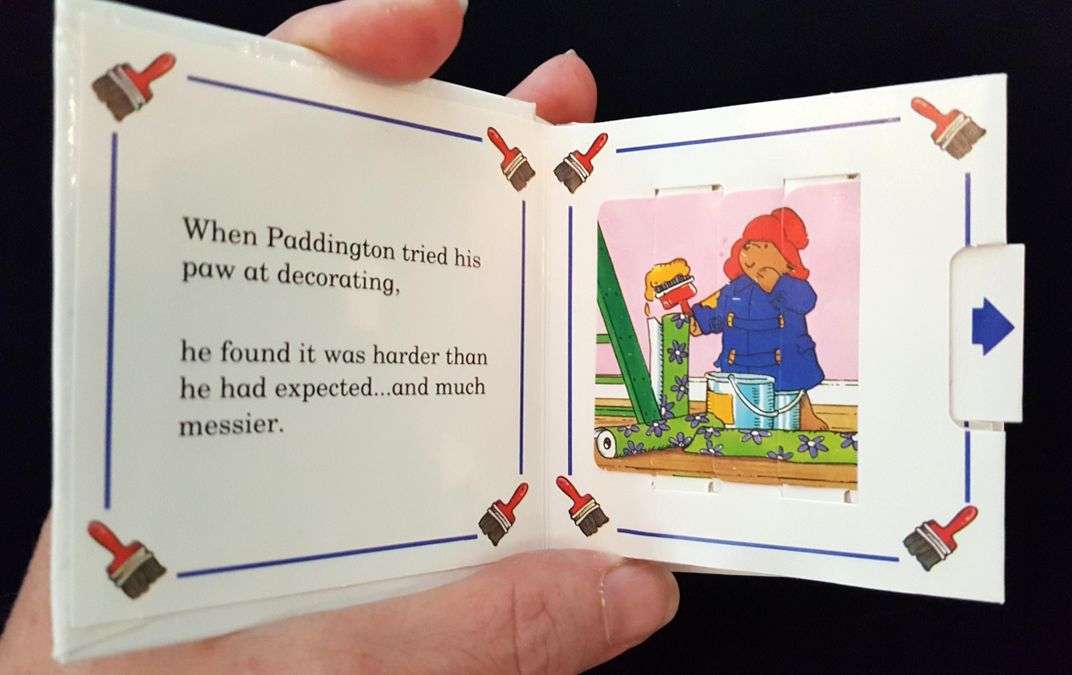

Three-dimensional or movable books are animated works that are created by “paper engineering.” A pop-up has parts made from stiff card stock that move when a page is turned. A sliding book, also known as a pull tab, or a dissolving image mechanism, has a Venetian-blind type of construction animated by a small flap that causes the image to transform into something different.

The dust-covered pop-up in the movie Paddington 2 is made up of beloved city landmarks: “And this is London.” The moment conveys the absorption that a child can have in books and their illustrations and construction. In 2014 Bond reminisced about childhood: “I think the most precious thing you can give a child is your time. And I think the next most precious thing you can give a child is an interest in books. If you’re brought up with books being part of the furniture, with a story being read to you when you go to bed at night, it’s a very good start in life. I never went to bed without a story when I was small.”

The Cooper Hewitt Design Library collects movable and pop-up books for the study of their illustrations and paper engineering as art. While the Paddington Bear stories were all written by a single author, Michael Bond, there have been a number of different illustrators over the years, among them Peggy Fortnum, Ivor Wood, Borie Svensson, John Lobban and Nick Ward. They all feature Paddington with the iconic floppy hat from the first book in 1958 (The blue duffel coat and boots appeared later).

In the first story, Paddington is found by the Browns with a note “Please look after this bear. Thank you.” Bond has said he was inspired by child evacuees leaving London on trains during World War II. “They all had a label round their neck with their name and address on and a little case or package containing all their treasured possessions,” he said. “So Paddington, in a sense, was a refugee, and I do think that there’s no sadder sight than refugees.” Bond based Mr. Gruber on his literary agent Harvey Unna, who fled Nazi Germany.

The Cooper-Hewitt’s Library’s earliest edition of Paddington’s Pop-Up Book, from 1977, re-tells the story of the little bear that arrives in London from Peru with his battered suitcase. The books depicts Paddington Brown’s past life, travels, adventures and life in London, which usually involve a considerable amount of mischief and mishaps. This collection of the Paddington bear movable and pop-up books was the gift of Dr. Daniel J. Mason, and their Preservation was supported by a 2007 grant from the Smithsonian Women’s Committee in 2007.

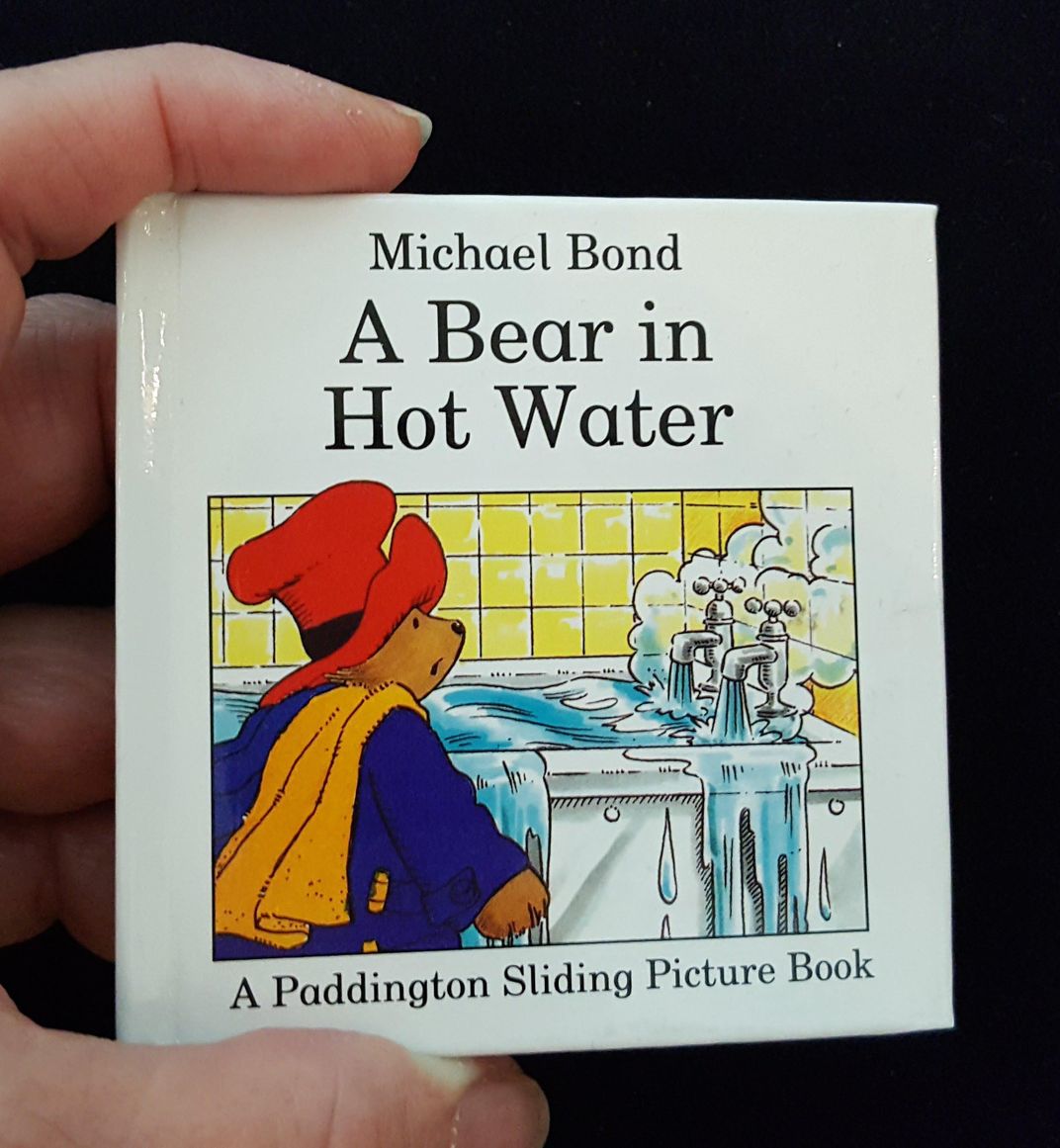

The popularity of movable and pop-up books continues to grow. They are designed in all sizes and shapes, with many innovative pop-up construction forms. A Bear in Hot Water from 1995, and A Spot of Decorating, also 1995, are examples of a mini sliding picture book, measuring only 3 ½ “ x 3 ½ “ square in size. The latest is the 2017 Paddington Pop-Up London, which is sure to enchant another generation with movable books. That book’s construction bears many similarities with Jennie Maizels’ Pop-Up London of 2011. While that title is not in the Libraries collections, the Cooper-Hewitt does have three earlier examples of the artist’s work: The Amazing Pop-Up Music Book, The Amazing Pop-Up Grammar Book, and The Amazing Pop-Up Multiplication Book.

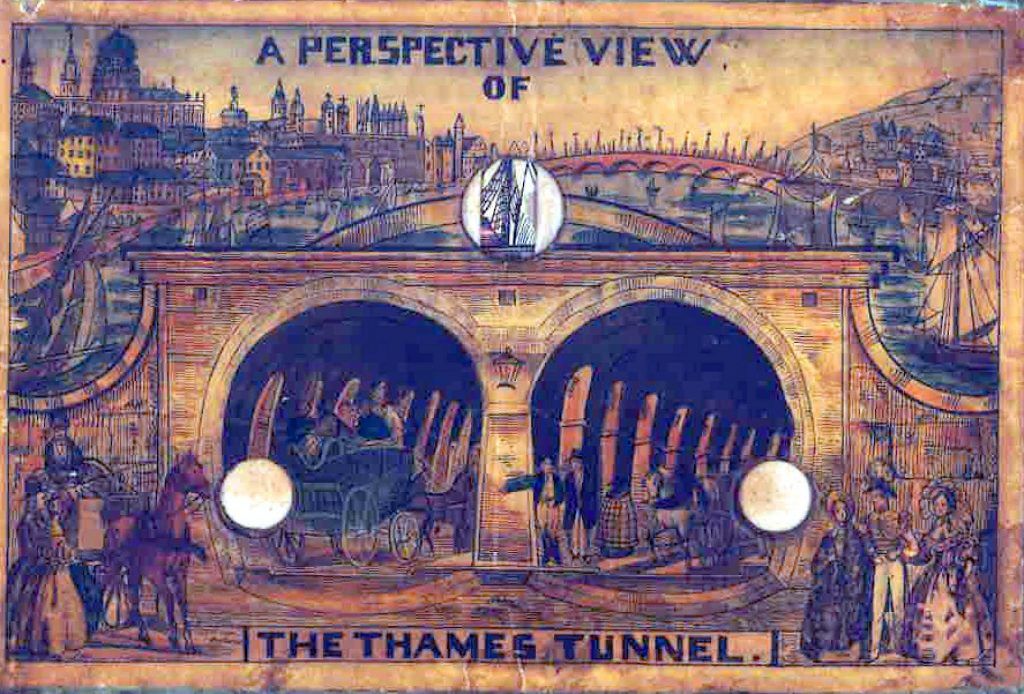

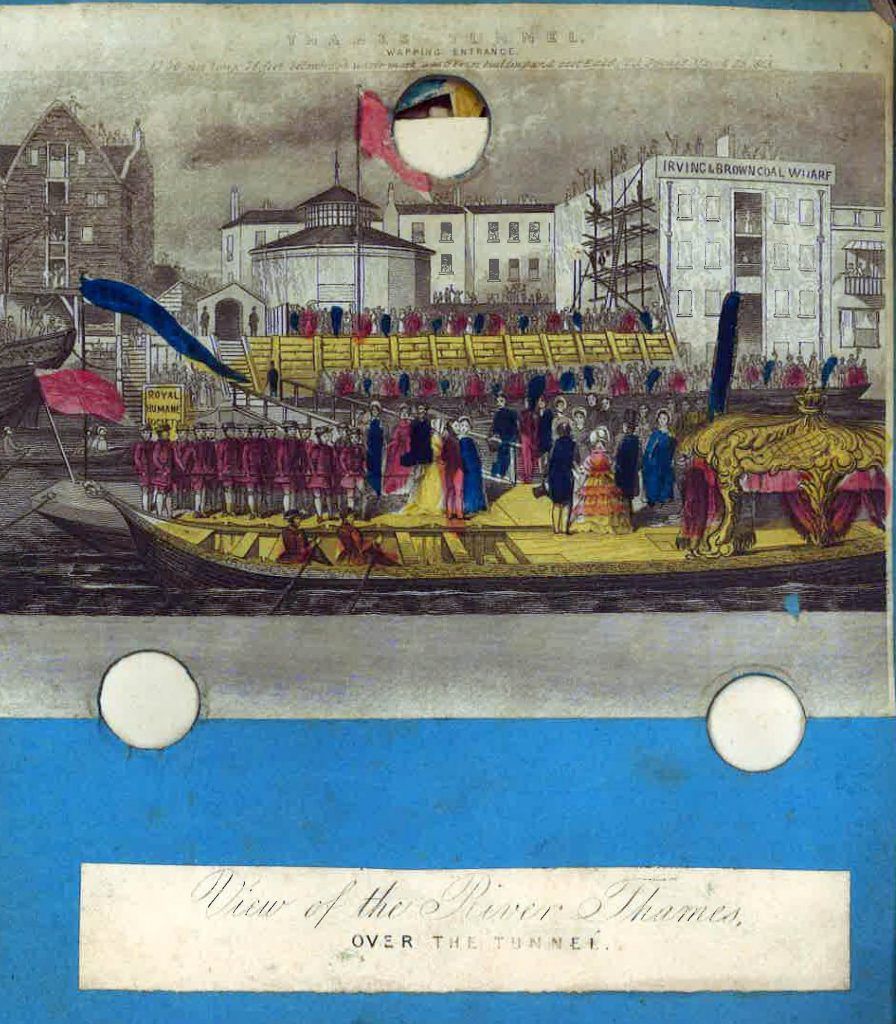

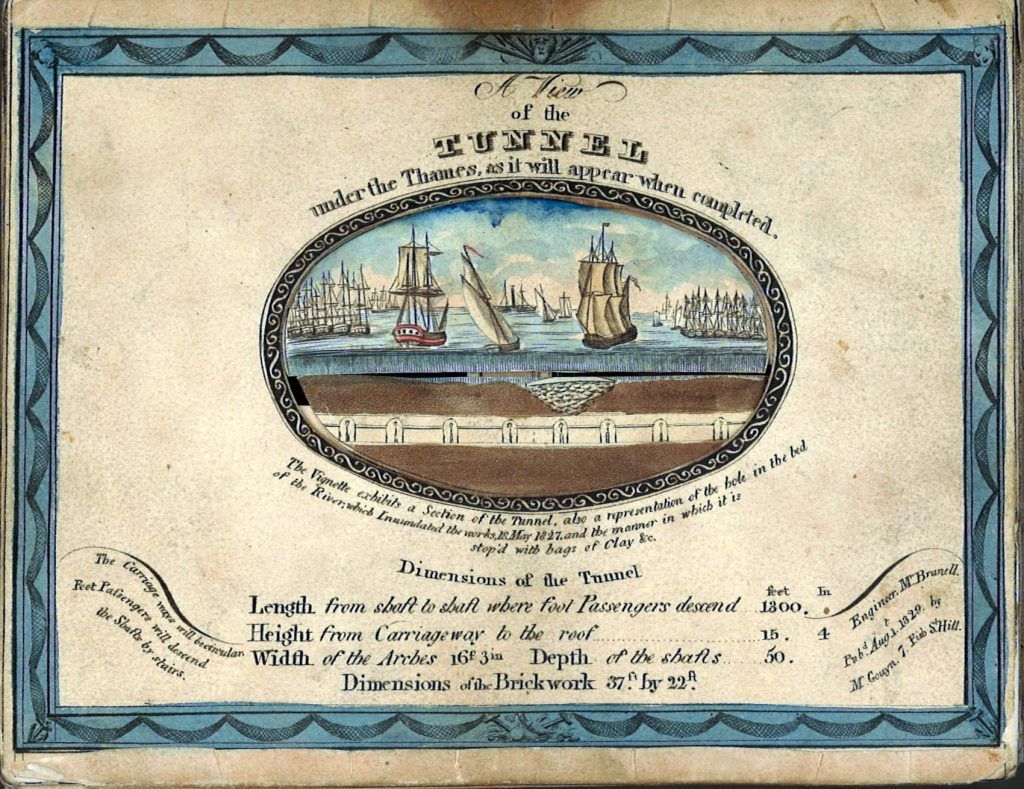

In the film, the River Thames dominates in the Paddington pop-up book—the ocean liner coming in under Tower Bridge, the dockyards, Big Ben and the Houses of Parliament giving way to the view of the boat traffic on the river. The Smithsonian’s Dibner Library of the History of Science and Technology in Washington, D.C., has a remarkable collection of other movable novelty books portraying the Thames Tunnel and the river in a similar way. So influential and widely distributed were these paper-engineered books of this then-called “Eighth Wonder of the World” that the term “tunnel book” came to be used for the previously more common “peepshow.”

The Thames Tunnel was built between 1825 and 1843, joining the south and north banks. Originally meant for horse-drawn carriages, this channel under the Thames became a pedestrian passage way with arcades for shopping and entertainment. It was constructed with years of arduous work and disasters by Marc Brunel and his son, Isambard, employing the engineers’ innovative “tunneling shield” technology.

The worldwide excitement of this technological marvel, the first tunnel built under a navigable river, was a great subject for the increasingly popular “peepshow” publications. They are made up of a set of etched, engraved or lithographed illustrated vignettes, attached to accordion sides of a perspective box. This construction, when extended, creates three-dimensional views observed through a hole in the cover. This form of printing art began in the 15th century as a means for scientists and artists to study optics and perspective. By the 19th century, peepshows, with inspiration from stage scenery, found a more general audience.

The Dibner Library houses an extraordinary range of Thames Tunnel peepshows as well as other related material, representing those produced when the digging was just starting, around 1825 (with perhaps the first) into the 1850s. There is a theme of inclusion in these tunnel books. Visitors in foreign dress mingle in the melting pot that was and is London. But the technological marvel of the Thames Tunnel had a short, public existence. It was closed in 1869 and became a railroad line.

The idea of connecting France and Britain by tunnel under the English Channel began as early as 1802, by mining engineer Albert Mathieu-Favier. The Dibner Library has many of the early printed proposals. Our hero, the well-traveled Paddington in the form of a furry stuffed toy, was suitably chosen by the British to be the first object to be passed through “The Chunnel” to France when the two sides were finally joined in 1994.

A version of this article originally appeared on the blog, Smithsonian Libraries “Unbound.”