The Revolutionary War Patriot Who Carried This Gunpowder Horn Was Fighting for Freedom—Just Not His Own

Simbo, an African-American patriot, fought for his country’s liberty and freedom even as a large population remained enslaved

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cb/3f/cb3f72e3-8da3-43d7-b284-35b8ac0ced13/prince-simbo.jpg)

Perhaps nothing demonstrates the American story more provocatively than an artifact that belonged to an African-American soldier, fighting during the Revolutionary War for the independence of the United States, even as his own freedom remained in question.

The artifact, a carved cow horn used to carry gunpowder now held in the collections of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, belonged to the American Revolutionary patriot fighter Prince Simbo.

“There are very few objects that have survived from that time period that were actually owned by an African or African-American,” says the museum's curator Nancy Bercaw. “For an object like that to have survived is just remarkable.”

The horn is emblematic of what Bercaw describes as the “paradox of liberty” that pervaded the country, as the nation fought for independence, with themes of “liberty” and “freedom” central to the war effort, even as a large segment of the population remained enslaved.

The importance of this idea is made clear on the powder horn itself, which is prominently engraved with the word “liberty.” It also includes Simbo’s name and a number of symbols. Among these is the “all-seeing eye.”

“For Africans in America, the question of liberty was much deeper and more significant than just the American Revolution itself,” says Bercaw. “They were really fighting for personal liberty in a really profound way. So they were willing to fight for whichever side was likely to secure them the most liberties.”

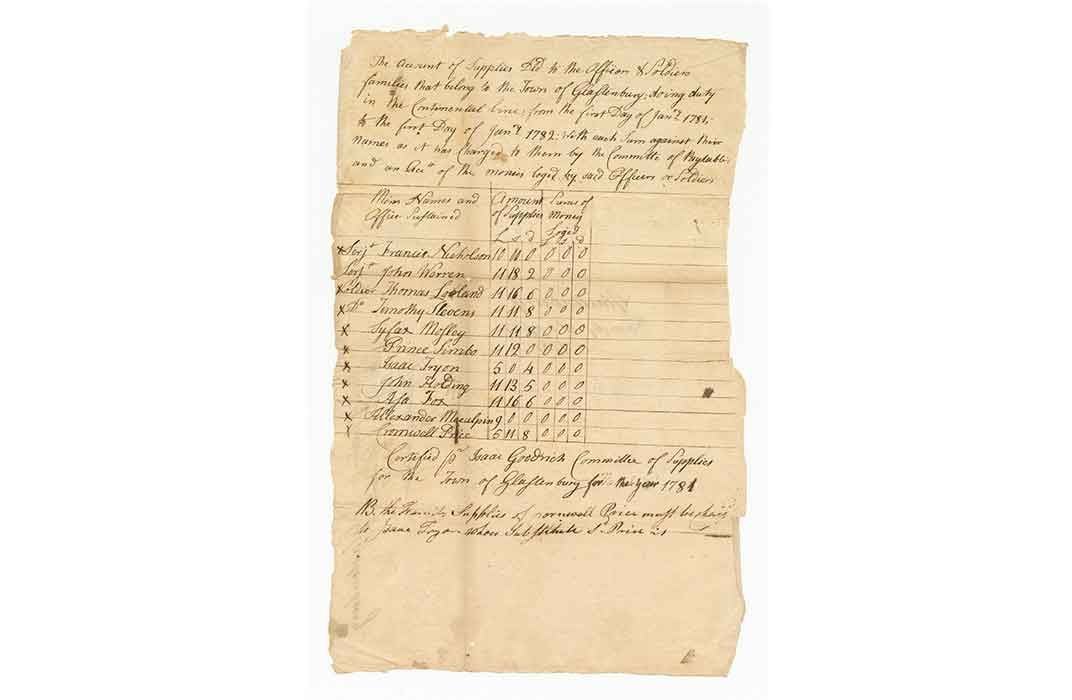

Unfortunately, little information about Simbo has lasted, beyond his war records. It’s known that he lived in Glastonbury, Connecticut (the city’s name is engraved on the horn), and signed up to serve in the American Revolution in 1777.

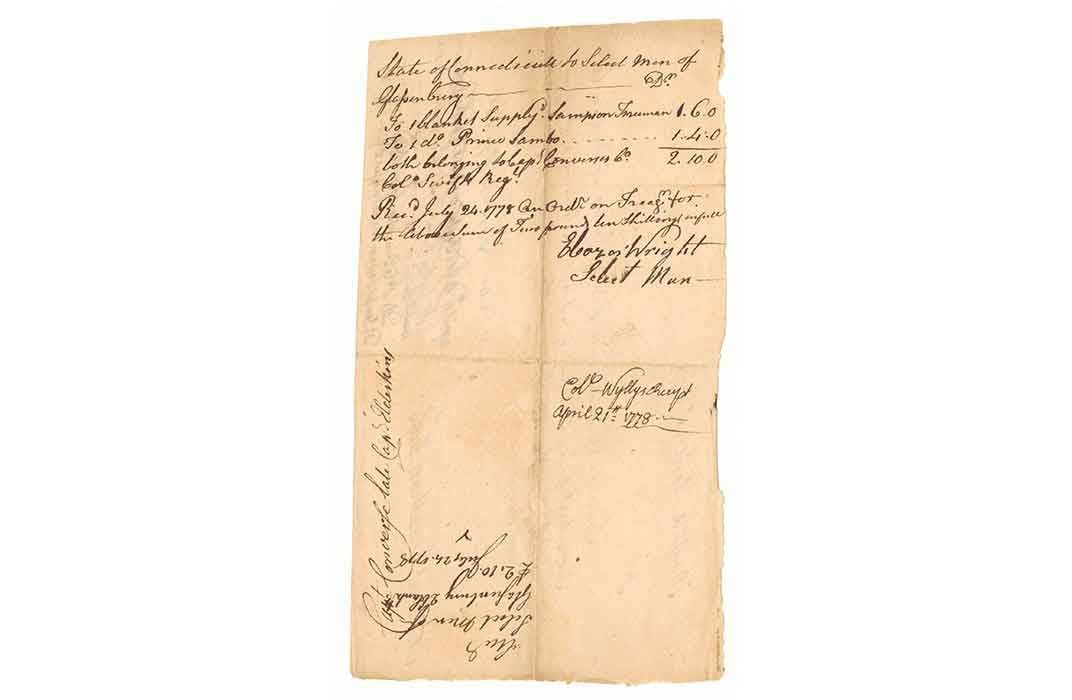

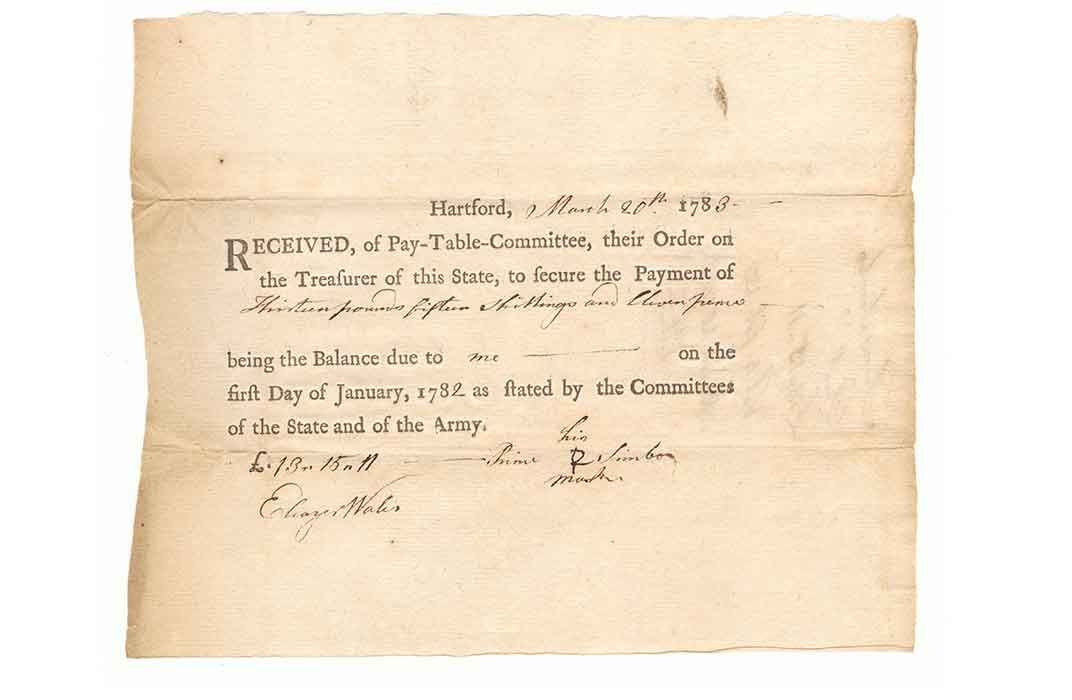

According to muster rolls [enter search terms "Simbo" and "Connecticut"], he was enlisted into the army on Feb. 23, 1778, and served in the 7th Connecticut regiment, under Captain Ebenezer Hills, Huntington’s Brigade, First Division. His regiment served in the Battle of Brandywine, Battle of Germantown, and Battle of Monmouth, before being merged into the 5th Connecticut Regiment in 1781.

Simbo would have been one of about 10,000 African-Americans who served in the revolution on the patriot side. While the museum has been unable to confirm whether Simbo was enslaved or a freeman, it is likely he was the latter.

“My guess is that he was a free black man,” says Gary Nash, distinguished research professor at UCLA, who has studied and written extensively on the lives of African-Americans during the Revolutionary War era. “He would likely not be serving beside his master while enslaved—that would be unusual.”

Nash is the co-author, with Graham Hodges, of Friends of Liberty, which recounts the life of Agrippa Hull, an African-American patriot who served in the war, and he expects that Simbo would have enrolled as a free person, similar to Hull.

Quite a few African-American men from Connecticut served, in a unit growing out of the old militia service, so there is a possibility that he had previously served in the Connecticut militia. If that were the case, that would mean Simbo likely had more significant rights and privileges associated with membership to the militia, according to Bercaw.

If he had been a slave, serving in the war might have been a chance to attain greater rights, if not full freedom.

“This was a huge gamble,” says Bercaw. “People really assumed that [greater rights] would be coming, and we find that during the American Revolution a lot of African-Americans petitioned their states for freedom, and this is when states like Massachusetts begin abolishing slavery—but many African-Americans served in the Revolution as enslaved people and after the war continued to be enslaved. It wasn’t a guarantee.”

She points to one woman in particular whose petition for her freedom to Massachusetts set off a chain of similar petitions and campaigns for abolition, though very few abolished slavery altogether. Connecticut instituted “gradual emancipation,” requiring enslaved people to serve 25 years before receiving full freedom. The last person was not freed until the 1840s.

“The gunpowder horn really speaks to Simbo’s personal story—there’s something very powerful about an object that was actually owned and possessed by an individual,” says Bercaw. “When you encounter an artifact like this, you consider a more basic, common community. It’s important in that light.”

“It’s also important because when people think of the past in African-American history, they tend to think of slavery. We are trying to make it a point that American freedoms have come out of the African-American experience, and this object is fabulous for telling this story.”

Little information remains of who has had the horn over the years. The Smithsonian received it in 2009 from Mark Mitchell, a notable collector and authority on African-American objects and ephemera. Says Bercaw, “As a curator, when I look at that object and see other objects [from Prince Simbo that include pay stubs and small paper slips related to his military service] that are on the market, it makes me think that it was in family hands, that that collection was whole at a certain time. Because for those things to have survived over the years, they would have had to have been stored.”

“Our most interesting collecting has been done through families,” says Bercaw. “Some families were really conscious of the history they were holding on to, and our museum has been lucky as people are trusting our mission more and trusting us with objects they have held on to for generations.”

It is one of the museum’s signature objects, displayed as part of the exhibition titled “Slavery and Freedom,” in its own case in the Revolutionary War era.

“History often remains impersonal—often it’s names and dates,” says Bercaw, “but having an object that belonged to an individual really helps people grasp the intimacy of what it was like in the past to be facing those contradictions, and to understand someone like him.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alex_Palmer_lowres.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alex_Palmer_lowres.jpg)