Peering into the Secret Diaries of American Artists

A new Archives of American Art exhibition looks at how artists documented their lives before social media

One spring day more than a century ago, Blanche Lazzell wrote in her diary: “This book is not intended for other eyes than the writer’s, and when they are forever closed, I hope this book will be laid in the fire.” Lazzell was 21 years old at the time and would later become a celebrated printmaker and artist. And despite her wishes for privacy, her diary found its way into the permanent collection the Smithsonian Archives of American Art, and is now on view in an exhibition, “A Day in the Life.”

The exhibition opened September 26 in the Archives' Fleishman Gallery, which is located on the first floor of the building that also is home to the National Portrait Gallery and the Smithsonian American Art Museum. The complete diary collections of three artists are on display, as well as 35 opened diaries from other artists. Some are large leather-bound journals; others are just bigger than a matchbook or torn from a magazine advertisement. Some contain elaborate illustrations, perhaps done in anticipation of being viewed one day; others came under lock and key, like the 54 diaries belonging to sculptor Katharine Lane Weems, which a curator had to pick open with a paperclip.

Though putting pen to paper and taking the time to describe one’s day may now seem quaint, diary keeping has endured in the digital age. The most contemporary work in the exhibition is a video installation by Joe Hollier, created this year. Hollier says that he has tried to keep several traditional diaries over the years, to no avail. “I felt like I was supposed to write about the details of my day, and it seemed boring to me,” he says. When he moved beyond writing in a notebook, however, he found it easier to express himself. “When I think back about the last few years of my life, I tend to think of it in phases of the specific pieces I was making at that time. So the process is how I relate to time and I've made that process my 'diary.'” His installation incorporates animations and clippings to document his artistic process.

“A lot of people [now] might consider themselves diarists but in a more public way,” says Mary Savig, curator of manuscripts at the Archives. “The idea of privacy in diaries is shifting.”

“The people of today write blogs or have a Tumblr or Facebook,” says deputy director Liza Kirwin. “In some sense, people are keeping more diaries than ever now in those new forms.

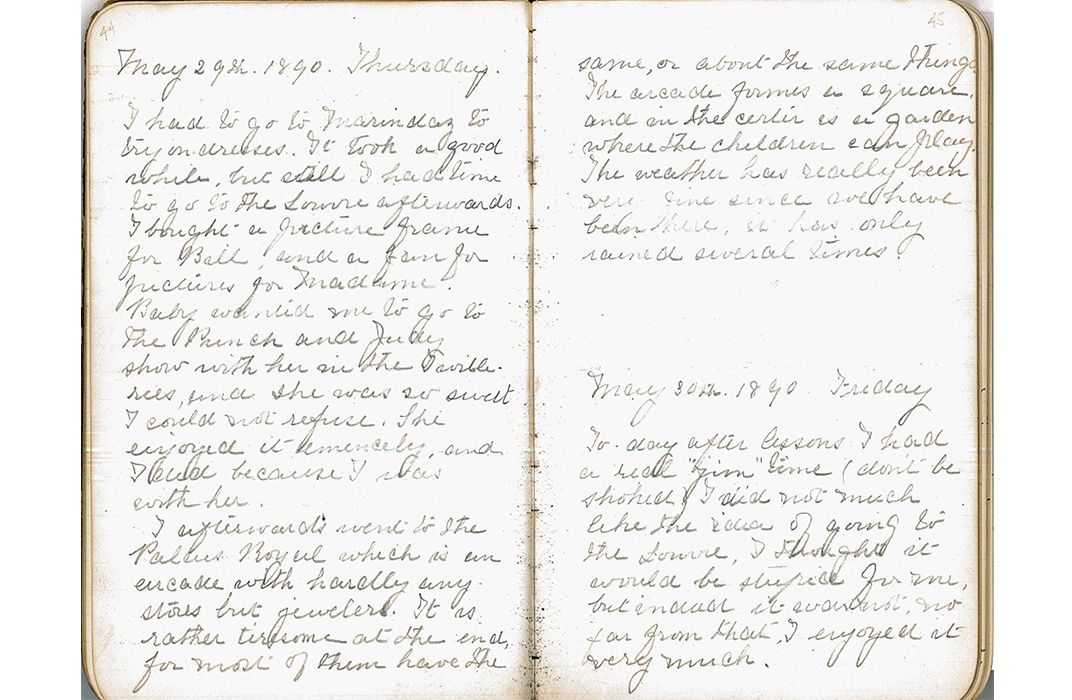

While the formats may be changing, the content of diaries has not. “You get a sense that teenagers through time are always the same,” Savig says. Writing 124 years ago, 15-year-old Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney described the food she was eating while on vacation in Paris. Nowadays, Savig points out, she would simply Instagram it. And just as people now flock to Twitter to comment on historical events, the Archives diarists wrote about the assassinations of Abraham Lincoln and John F. Kennedy, the end of World War I, and September 11. Upon hearing news that the Titanic sank, portraitist Cecilia Beaux, then 56, wrote that it was “a most unjust and unnecessary blunder or rather stupid reckless carelessness of everything by speed for the rich.”

The Archives has digitized the diaries and is seeking help transcribing them. The Archives curators say that diaries offer a greater level of intimacy than other media. Diaries help in “really understanding the complexities in somebody’s life,” Kirwin says. “You’re there with the person writing it….A diary is somehow truer.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/MAx2.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/65/0b/650b4c8a-a3b5-4f72-8d75-b7d242d49c52/aaa_pealrube_0001p1-1.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fc/18/fc18cf8b-07a7-4332-983e-20ea8621dc5a/mora2-1.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ee/f9/eef9cc7a-0545-45d6-99f8-8cb6e82cbfa1/mccoy-1.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d6/18/d618e116-1333-4091-8d06-e95d0d36da7b/lowry-1.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f4/97/f4977c7e-b99b-4e55-898a-1a66a840aaa6/cornell-1.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fd/df/fddf05e6-4bb1-4ab0-b5b3-fba8625d0e42/portrait_of_rubens_peale-1.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/MAx2.jpg)