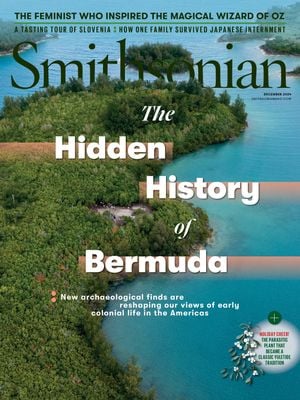

The ‘Penicillin Girls’ Made One of the World’s Most Life-Saving Discoveries Possible

The true, forgotten and sometimes-stinky history of the cohort who took Alexander Fleming’s innovation and forever changed the face of modern medicine

:focal(1200x903:1201x904)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/53/5d/535dbb9a-4aab-4df0-870a-bef3061bc7b9/primary.jpg)

For many people, a bloom of mold symbolizes failure. But this small medallion of mold, its two dots of Penicillium notatum blossoming like fungal flowers frozen in eternal spring, represents an astounding success. It’s the mycelial spark that touched off an antibiotic revolution.

Scottish bacteriologist Alexander Fleming recognized the potential of Penicillium mold when he found it growing in his less-than-tidy lab at St. Mary’s Hospital Medical School in London in 1928. While experimenting on the disease-causing Staphylococcus aureus bacterium, the sharp-eyed Fleming noticed protective halos around some flecks of blue-green mold, which were inhibiting the bacteria’s growth. He first colorfully dubbed the substance “mold juice,” later changing it to “penicillin,” after the fungus that produced it. Fleming announced his discovery’s infection-fighting potential to little fanfare and then, with the help of two young researchers, tried purifying penicillin in the 1930s, but he was unsuccessful.

Today, Fleming is often remembered as the lone genius in the lab who, thanks to keen eyes and a strange accident, brought penicillin to the world. In fact, to unlock mold’s true therapeutic promise would take many more people, years of labor, a war and a very special moldy cantaloupe.

Around a decade after the Scottish microbiologist’s chance discovery, a University of Oxford team picked up Fleming’s work on penicillin, just as Europe was on the brink of another world war. By 1940, the Oxford team, guided by Howard Florey, Ernst Chain and Norman Heatley, managed to isolate and purify enough penicillin to save four lives—a major medical breakthrough, even though the lives belonged to mice.

Producing enough penicillin to save human lives would not prove simple. Fleming’s Penicillium preferred growing on the surface of a nutrient-rich liquid—or “mold broth,” as Fleming dubbed it—and, even with vast volumes of broth, produced scant amounts of the antibiotic. The Oxford lab got creative in finding more surface area on which to cultivate the mold, growing it practically everywhere, from bedpans to bathtubs. Eventually, the team developed a special fermentation container that looked a bit like a vintage gasoline can, with a side spout for pouring. Surrounded by dozens of these ceramic fermentation vessels in a kind of mold factory, six female technicians known as the “penicillin girls” carefully cultivated the Oxford team’s prized penicillin supply, pumping out a few milligrams each week for experiments and clinical trials. “From there, they have to separate out the tiny bit of actual penicillin they’re going to get from all that. It’s like making maple syrup,” says Diane Wendt, a curator in the Division of Medicine and Science at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

But even these moves couldn’t produce life-saving amounts of antibiotic, and with Nazi Germany’s Blitz on London imperiling U.K.-based research, in 1941 Florey and Heatley carried Fleming’s mold to the United States, hoping to create higher yields on safer ground. Their unlikely journey brought them to Peoria, Illinois, and a U.S. Department of Agriculture laboratory fit for cutting-edge fermentation experiments. One key discovery at the lab was to cultivate the mold more efficiently by sinking it in deep tanks of a starchy brew.

Still, Fleming’s mold wasn’t growing bountifully in these new conditions. The USDA team needed to explore tougher, more productive strains and species of Penicillium mold. So they gathered members of the U.S. Army Transportation Corps along with researchers and laypeople to begin searching for new mold specimens amid stacks of spoiled bread, cheese, meats and produce, and scanning the rich microbiota of soils from as far as Australia and India. By 1943, someone finally did strike gold with the most productive penicillin mold from a musty melon—a mysterious woman history has nicknamed “Moldy Mary.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f2/b3/f2b3876d-b9cf-48da-917b-745056100533/reverse.jpg)

Confusingly, while one technician at the Peoria lab, Mary Hunt, also bore this nickname, in fact, the true Moldy Mary was probably an anonymous Peoria woman who handed an old cantaloupe to a lab guard, in one of history’s most underrated gifts. What’s certain: Thanks to a funky cantaloupe’s exceptional ability to produce penicillin—six times the amount of Fleming’s mold—the mass-production of antibiotics was finally possible. Penicillin has since saved more than 80 million lives.

In 1945, Fleming, Florey and Chain received the Nobel Prize for their contributions to penicillin’s discovery and applications. Then, in 1953, a curator at the Smithsonian wrote to Fleming, asking him to donate materials from his lab for an exhibition. The microbiologist sent a commemorative culture he’d prepared from the original Penicillium mold. This two-inch sample was grown on blotting paper and sealed behind a small round glass. In early 2025, the symbolic, dried mold will return to display as part of a medical history exhibition, “Do No Harm”—a reminder that history’s great discoveries can come from the most unprepossessing places.