In Persia’s Dynastic Portraiture, Bejeweled Thrones and Lavish Decor Message Authority

Paintings and 19th century photographs offer a rare window into the lives of the royal family

:focal(2452x2642:2453x2643)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/77/e5/77e56b99-3f16-4faa-90fd-7ed469349a2c/s20134_001.jpg)

Weeks after the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery unveiled portraits of former President Barack Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama, the paintings continue to generate mixed reactions and crowds of visitors waiting patiently to take selfies with the artworks. Over at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, other portraits of power have joined the Obamas with a little less pomp and press. “I don’t expect people to rush to see these guys,” Simon Rettig says, chuckling.

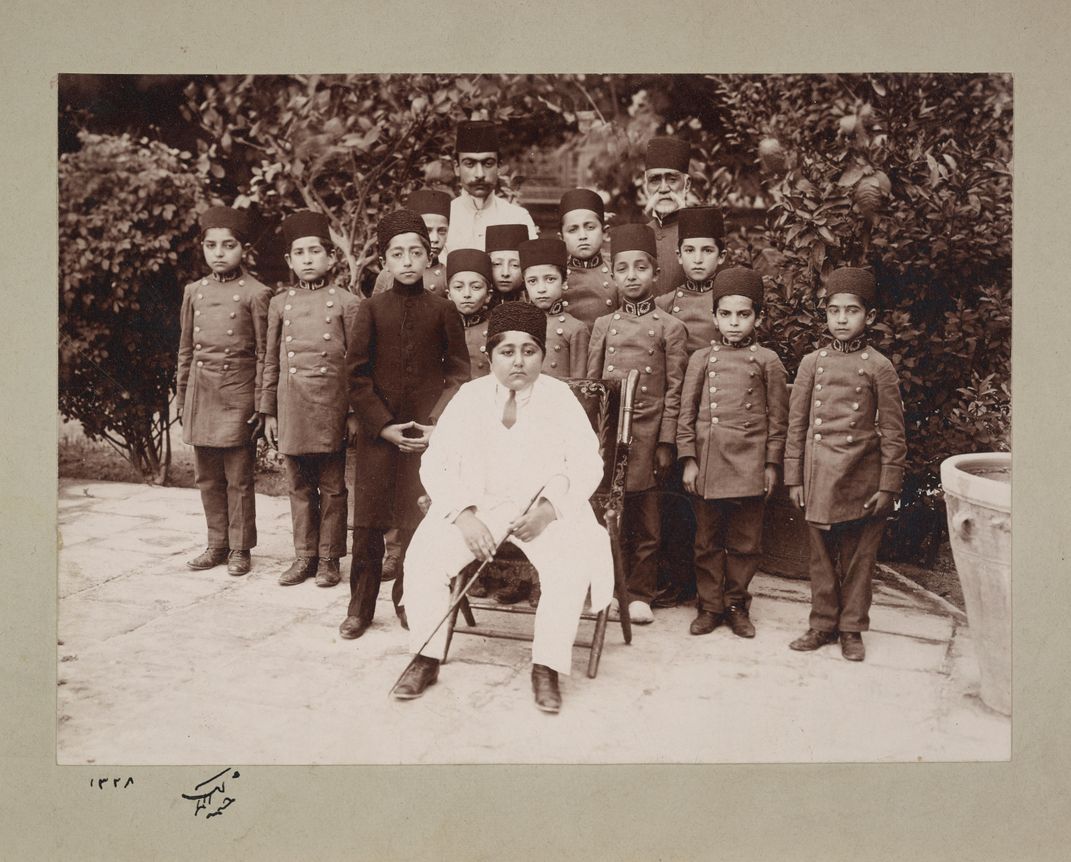

Rettig is the assistant curator of Islamic art at the Smithsonian’s Asian art museum, the Freer|Sackler Gallery of Art, and when he says “these guys,” he means the Qajar shahs, leaders of a Turkmen ethnic group that ruled Persia from 1779 to 1925. A new exhibition, “The Prince and the Shah: Royal Portraits from Qajar Iran,” features paintings and photos of the monarchs, their cabinets and their families.

The Qajar dynasty roughly corresponds to what historian Eric Hobsbawm called “the long 19th century,” which began with the French Revolution in 1789 and ended with World War I. Persia’s first Qajar shah, Aqa Muhammad Shah Qajar, ravaged the Caucasus and what is now Georgia to bring these areas and the family’s ancestral lands in present-day Azerbaijan under Persian rule. He established Tehran as the capital and Golestan Palace, a lavish complex combining traditional Persian artistry with 18th-century architecture and technology, as the family’s home and seat of power.

Aqa Muhammad was assassinated in 1797 and succeeded by his nephew Fath-Ali Shah Qajar. A contemporary of Napoleon Bonaparte who, like the French statesman, explored passions outside of politics, Fath-Ali grew his family residence into a nerve center of creative and cultural influence. The second Qajar shah took a particular interest in portraiture as propaganda. “These portraits were meant to assert the power of the shah,” Rettig explains, signaling to rival Qajari factions and to such international audiences as the Ottomans and British and Russian Empires “that the country was unified under his authority.” Yet Fath-Ali struggled to maintain Iran’s sovereignty over the territories his uncle’s forces had conquered, whether through military might or diplomacy.

To burnish Fath-Ali’s political reputation, an unknown supporter of the shah or maybe the shah himself commissioned an illustrator to modify the country’s most popular text. From around 1810 to 1825, an unnamed artist drew Fath-Ali into a manuscript of the Shahnama (The Persian Book of Kings). Complete with his characteristic long black beard, Fath-Ali appears as the holy warrior Rustam who rescues the Persian hero Bijan, and by extension, as the leader who protects Persia from its enemies. Rettig says this Shahnama manuscript, copied by calligrapher Vali ibn Ali Taklu in 1612, has never been studied until now. He’s presenting a paper on this manuscript at a conference on Iranian studies.

Over the course of his reign, Fath-Ali commissioned more conventional royal portraits, such as a watercolor and gold painting in the exhibition in which he’s seated on a bejeweled throne, surrounded by his sons and court. These early Qajar portraits introduced a quirky combination of Eastern and Western painting techniques that soon proliferated in Persia: realistic, detailed facial features you’d see in Renaissance- and Baroque-period European paintings plus the flat, two-dimensional treatment of the subject’s body and garments found in traditional Iranian works. The Qajar images appear as if the artists placed paper-doll clothing over the shah and transcribed what they saw. Western historians at the time didn’t exactly love this hybrid style.

Yet artistic approaches would inevitably mix, especially after 1840, when “Iranian painters trained in Iran were sent to France and Italy in order to get familiar with European techniques from the past but also to meet with living artists,” Rettig explains. European painters visited Iran throughout the 1800s, as well. Portraitists for the Qajar royals borrowed from other European eras, with some artists choosing a Romantic style. These paintings centered on the shah or one of his family members seated or standing in front of a landscape background framed by a luxurious curtain. The popularity of Romanticism in royal portraiture reached its peak during the rule of Fath-Ali and that of his grandson and successor Muhammad Shah Qajar, who ruled from 1834 to 1848.

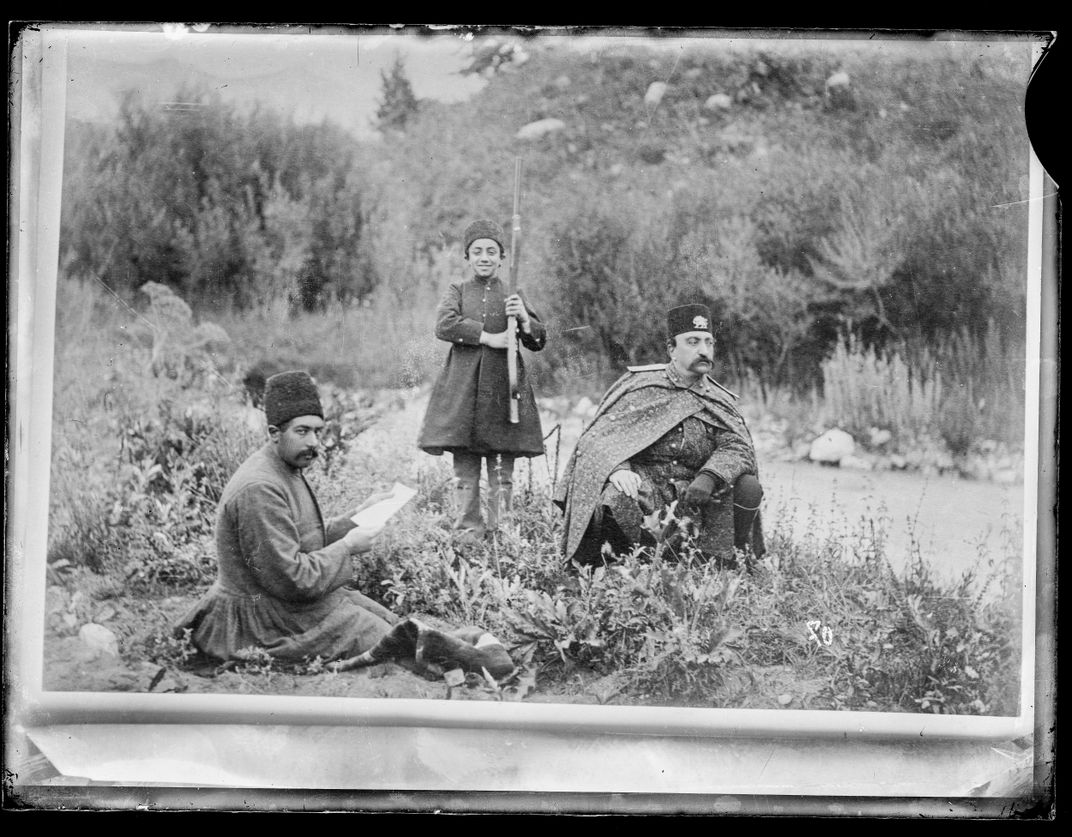

By then photography had arrived in Iran and had ignited the imagination of Muhammad’s son and heir Nasir al-Din Shah Qajar. As an amateur photographer himself, Nasir al-Din seized every opportunity to document his personal and political lives on camera: a hunting trip, a meeting with his cabinet, even what looks like a teeth cleaning from his Austrian dentist. His grandfather Fath-Ali may have loved the painter’s spotlight, yet one could argue that Nasir al-Din made himself king of the Qajar selfies. He was the longest-serving shah, leading Persia (and perhaps Persian photography) from 1848 to 1896.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f2/94/f294759c-e5dd-4997-993a-099e57c681c0/s20169a-b_redo.jpg)

Unlike painted portraits, photographs of Qajar nobility were not intended for a broader audience outside of Golestan Palace. Instead, the family compiled these pictures in books or albums that they would show to individuals in a private setting. “You would not hang a photograph on the wall, at least not before the 1900s,” Rettig says. “So it was more of a private viewing than a public one.” Another family member who experimented with photography, Abdullah Mirza Qajar chronicled the Qajar court during the reigns of Nasir al-Din and Muzaffar al-Din Shah Qajar and gained renown as a highly accomplished photographer.

“What is sure is that photography [in Iran] was first developed at the court and for the shah,” Rettig says. “From there, it spread to other strata of the society, mainly elites and bourgeoisie.” Photography expanded beyond portraiture to include landscapes and photographs of cities, images that also documented and projected certain messages of wealth and power at a state level.

Rettig says that during these early days of photography, Persians did not think of photos as art, because they captured a person or a scene as a truthful moment in time, rather than conceiving such moments from whole cloth. As a result, he says, religious jurists didn’t issue fatwas against photography, since the photos did not compete with God’s creation. Photography chronicled the everyday work and domestic goings-on of the royal family, though photography-as-art eventually did begin to imitate painted art. Some royal photos featured shahs standing in front of fake landscapes; think of their present-day counterpart, the department-store backdrops for family photos.

“The Prince and the Shah: Royal Portraits from Qajar Iran” is on view through August 5, 2018 at the Freer|Sackler Smithsonian Asian Art Museum in Washington, D.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Elaine_Heinzman.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Elaine_Heinzman.jpg)