Personal Writings of Arthur C. Clarke Reveal the Evolution of “2001: A Space Odyssey”

Works donated from the author’s archives in Sri Lanka include letters to Kubrick and an early draft of his most famous novel

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/27/7a/277abff6-a01d-4949-96b4-7d99ba55f00e/may2015_g01_nationaltreasure.jpg)

I was once a teen from Texas, living in southern India during the early 1970s (my father had been dispatched abroad in the petrochemical-employment diaspora). That was how, as a science fiction-obsessed kid, I ended up in an audience in Madras when Sir Arthur C. Clarke arrived in the city on a lecture tour. Clarke, a British expat who made his home in the nearby island nation of Sri Lanka, was the first science fiction writer I’d ever met.

I stared in awe at the visionary sage as he addressed a crowd who included the city’s businessmen, clad in white cotton dhotis and jubbahs, sitting in wooden chairs in an air-conditioned hotel ballroom. Clarke told his audience two important things: Information should no longer be printed on paper, and Indians should keep up the good work with their space program. After his speech, Clarke, a bespectacled, round-shouldered man, joked with me in a donnish fashion as he signed a tall stack of my paperbacks. I’d innocently brought along my entire Arthur Clarke fiction and nonfiction collection, which filled a large bag.

Now it’s 2015. An Indian satellite orbits Mars, while I’m in my home study poring over pages from the Arthur Clarke personal papers, sent to me in a form Clarke would have appreciated: as electronic files. As it turns out, Sir Arthur C. Clarke, CBE, is likely the only author of fiction whose papers happen to be archived in a repository devoted to outer space—the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum’s Udvar-Hazy Center. Smithsonian curator Martin Collins and archivist Patti Williams recently acquired some 85 cubic feet of Clarke’s paper data, including photographs, shipped from Sri Lanka by FedEx.

One of the oldest and most numinous items is a battered high-school notebook. Its pages feature neat, hand-lined grids in which an adolescent Clarke lists his precious science fiction possessions. He rates the works, too—“good,” “very good” and the rare “very very good.” Young Arthur is particularly keen on H.G. Wells and Edgar Rice Burroughs, as indeed I was at his age—except that I had the benefit of reading heaps of Arthur C. Clarke.

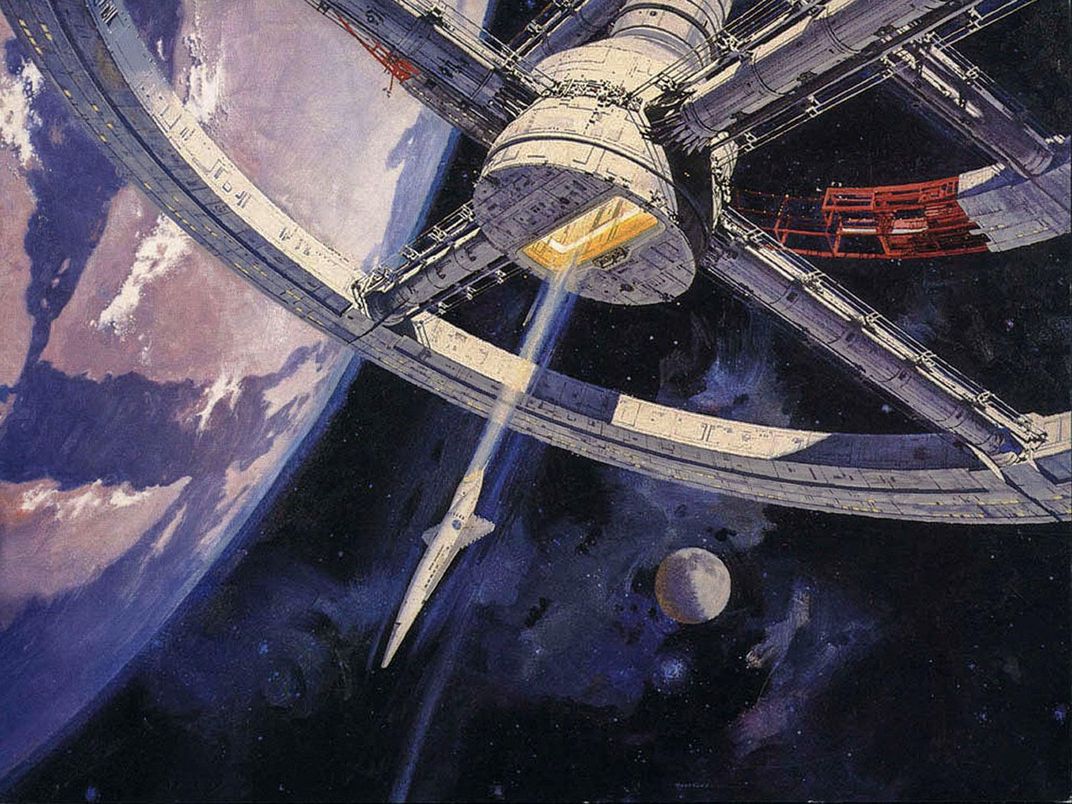

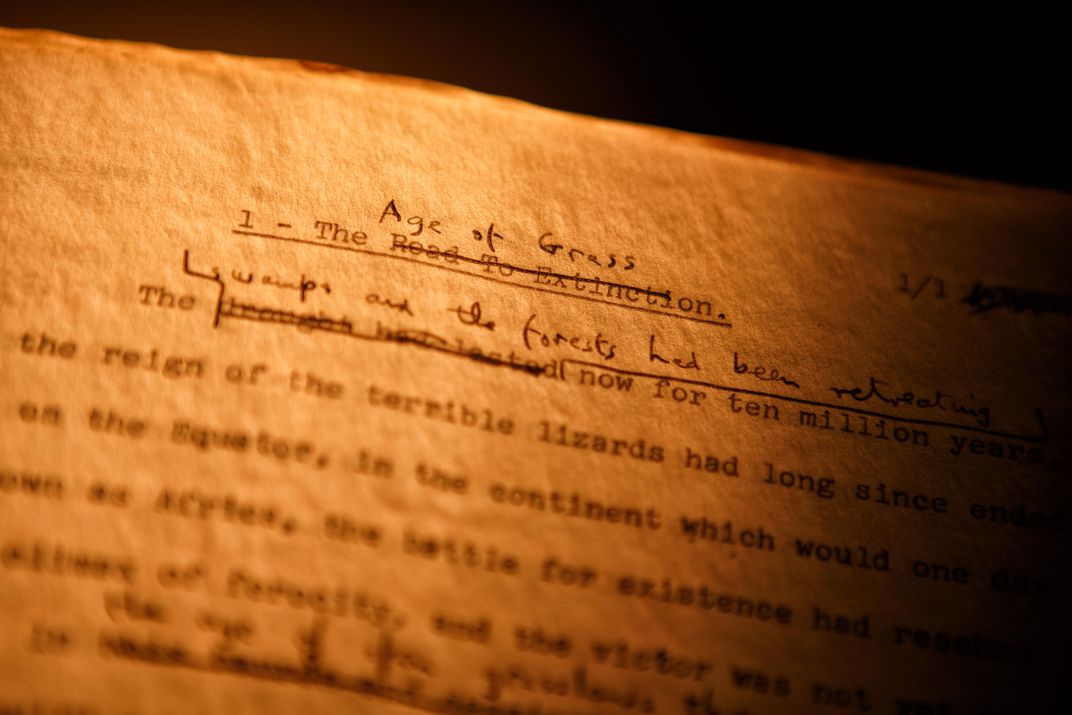

I noted, also, a few choice items related to that famous business with Stanley Kubrick. (Among the new Smithsonian holdings are an early draft of the novel 2001: A Space Odyssey.) The two of them, director and novelist, are conspiring to make what Kubrick describes in a letter to Clarke as a “really good science fiction movie,” because they both know that there is no such thing—not yet.

As they worked together, conjuring up the novel and the film, correspondence reveals a preoccupation with “the Cube” (later transmuted into the Monolith). Responding to Clarke’s suggestion in 1966 that the Cube communicate directly with the man-apes who would one day populate the film, Kubrick instead advocates an enigmatic presence: “We see only the hypnotic image appear and the spellbound faces of the man-apes.”

The “really good science fiction movie” was supposed to take two years to complete (it took four); it was $4 million over budget; the film nearly bombed in American theater chains before hippies flocked to watch it—a tale of spine-tingling terror, almost.

2001: A Space Odyssey bears the imprint of its source, Clarke’s short story “The Sentinel.” Clarke dashed off that lunar tale in 1948, only to have his big idea blow everybody’s minds a full 20 years later. Lags of that length were rather typical in the visionary’s life.

Clarke, a British émigré in Sri Lanka, must have been an ideal collaborator for Kubrick, an American émigré in Britain. In his limpid, clear, well-typed correspondence, Clarke briefs Kubrick on a dazzling panoply of severely weird topics: paleo-anthropology, extraterrestrial intelligence, scuba diving, the proper choice in home telescopes. Clarke cares not one bit for Hollywood glamour. He’s always informative, yet never intrusive.

Sri Lanka was kind to Clarke. For years, he shipped his personal papers back to Britain for alleged safekeeping, then finally took the entire lot back to the island where he really lived, despite the risks of Sinhalese typhoons, tsunamis and civil war. His soul was British, while his mind was frankly extraterrestrial; eventually the lore had to go where the heart was. Now that cache resides in the museum where history probably wants it to be.

There were two kinds of fantasies in the Space Age: rocket-powered geopolitical fantasies with budgets of billions of dollars and rubles, and poetic paper fantasies made up by science fiction writers, especially one lone genius with an aqualung and a sarong. As decades pass, it gets harder for posterity to tell those world views apart. But Clarke always knew there was no real difference.

Related Reads

2001: A Space Odyssey