PHOTOS: A Gallery of Wildlife Caught on Candid Camera

From endangered pandas to wild horses, Smithsonian researchers are gathering countless photos of animals in the wild

A red fox in China was one of the animals caught on infrared cameras as part of a worldwide research effort. Courtesy of Smithsonian WILD

The well-being and status of endangered species, like the giant panda, depend on wildlife ecologists, who track and understand their communities. But, that’s not always an easy task.

“You never actually see the animal. All you see is the dropping from the animal,” explains researcher William McShea from the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute. “It’s such a frustrating life.”

Based in Front Royal, Virginia, McShea travels the world conducting large mammal surveys. But methods and technologies for doing that are continually evolving. “You can only get so far doing studies of panda crap.”

Hanging out, a giant panda takes a seat in China. Courtesy of Smithsonian WILD

In recent years, scientists have found increasing success using heat-sensing and motion-detecting technologies developed first for deer hunters. Called “camera trapping,” the practice employs infrared cameras. Since the scientific community began using this technique several years ago, there have already been breakthroughs, including getting the first-ever photographs of some species, according to Yale’s Environment360. McShea says when he started, scientists were still using car batteries to power these operations.

Now, with long-lasting digital camera, the researchers can do much more with much less.

Not only can a team track the movement of specific animals, but they can also learn more about animal behavior. For instance, elephants and bears regularly destroy the cameras, according to McShea. He’s not sure why they detect them when other animals don’t seem to, but they’re regularly photographed in the act of stomping down on a camera or even carrying another camera off into the wilderness. McShea and his team collect and archive these animalia candid moments at Smithsonian Wild, a website that can be searched for everything from rodents to marsupials to lions and bears.

Elephants and bears have been the roughest of all the animals on the infrared cameras. Courtesy of Smithsonian WILD

In China’s panda reserves, where McShea regularly visits, staff can now get a more accurate sense of how many pandas there actually are. In the process of monitoring the endangered species, McShea says they’ve also captured a wealth of biodiversity and learned more about what sorts of other species are living in the wild with pandas.

“This is the wave of the future for how we’re trying to record biodiversity,” says McShea.

Closer to home, McShea has been involved with a metro area project beginning in Rockville, Maryland, that tries to capture changes in wildlife presence and behavior as wildlife enter urban areas.

With all the data coming in from these and other sites, including the Appalachian Trail, McShea’s team has enlisted the help of “citizen scientists,” who can sign up to post a camera at a designated spot and retrieve the images later. Once uploaded, the photos can be tagged by the public. After enough people have identified an animal as a white-tailed deer, then the photo enters the searchable database online. Working along the Appalachian Trail, they found wild horses. Campers, however, remained off-camera because the Parks Service restricted camera placement to protect privacy.

There are currently more than 206,000 images on the site and more than one million collected.

“I’m a wildlife ecologist,” says McShea. “I had no intention of collecting photographs.” But McShea now sings the praises of camera trapping and works with other international wildlife groups to help coordinate data.

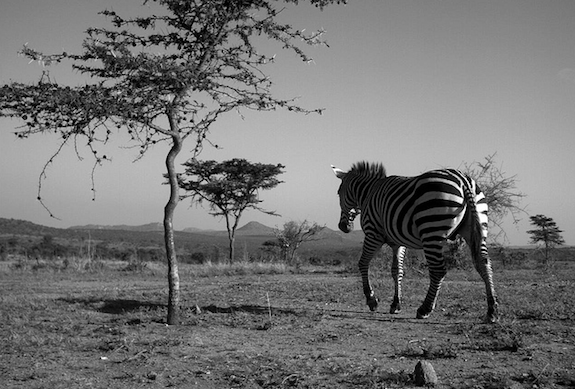

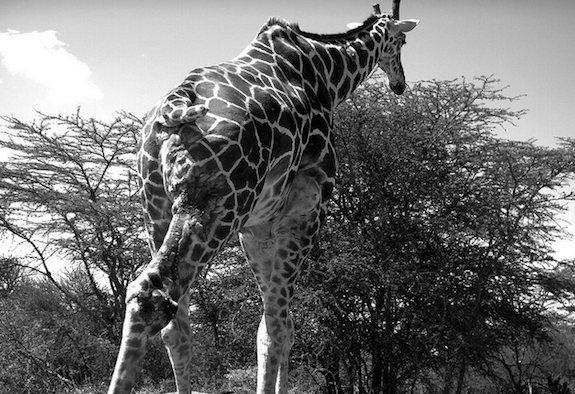

Perhaps the best outcome for the public, though, are the striking photographs themselves worthy of a glossy magazine spread.

A zebra in Kenya heads out for a stroll. Courtesy of Smithsonian WILD

A turkey vulture from Upstate New York spreads its wings. Courtesyof Smithsonian WILD

A giraffe saunters out of view in Kenya. Courtesy of Smithsonian WILD

Accidentally artsy photographs like this one of an ocelot in Peru are a treat to find. Courtesy of Smithsonian WILD

An ocelot poses for the camera in Peru. Courtesy of Smithsonian WILD

Cameras captured a takin poised to take a drink, in China. Courtesy of Smithsonian WILD

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)