These Photos Capture the Unity—and Defiance—of the Million Man March

Roderick Terry’s photographs are now housed at the National Museum of African American History

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fb/ae/fbae1176-d0bc-4feb-8489-2dbc05d167a2/2013_99_53_001.jpg)

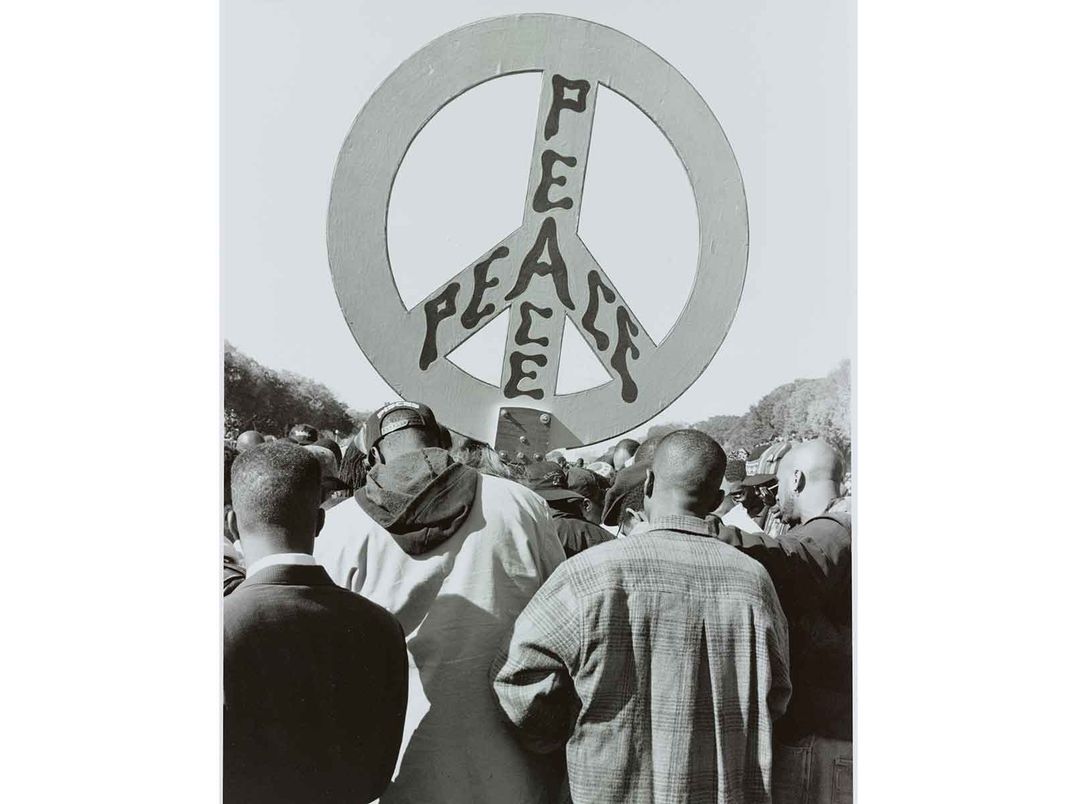

Photographer Roderick Terry recognized the significance of the moment. It was October 16, 1995, when he picked up his camera and set out to document the Million Man March, a remarkable moment in American history, when tens of thousands of African American men arrived in Washington, D.C. heeding the call of the rally’s organizers, the NAACP and the Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan. “We cannot continue the destruction of our lives and the destruction of our communities,” Farrakhan told the crowd in his more than two-hour speech, calling for atonement and a demand for self-discipline. The day would prove powerfully moving to those who came by the droves to unite and to pledge a commitment to black communities across America against a backdrop of racist coverage that sowed fears that would not come to fruition during the march.

“I decided that I wanted to create my own visual record,” Terry says. “I wanted to be able to capture the most accurate representation of the march possible. This was very important to me because I really didn’t believe all of the characterizations before the event even occurred. So I decided that I wanted to take matters into my own hands and document the march myself.”

The result is a breathtaking visual testament to the power of those who stood together in unity to focus on community improvement and to self-reflect. The Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture recently acquired 55 of Terry’s images captured on that remarkable October day, a quarter-century ago.

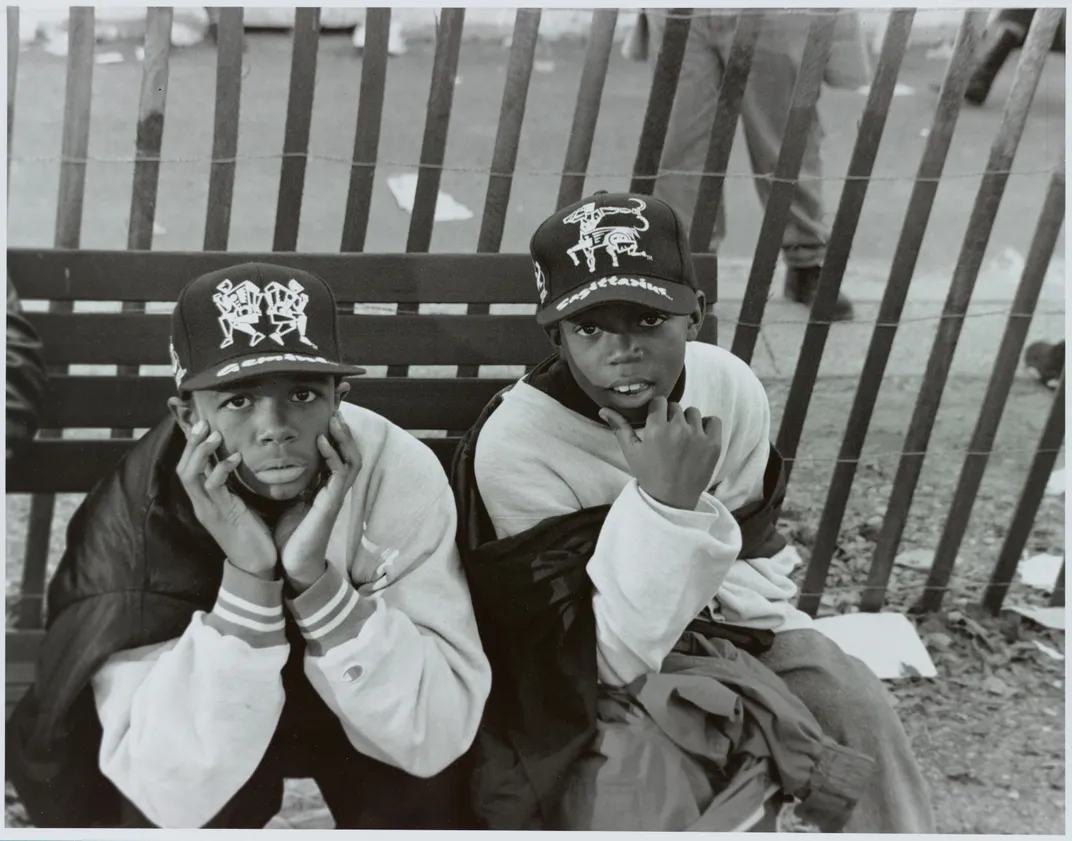

Terry grew up in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, and after studying at the University of London, earned his law degree at Howard University. At the time, he was working in the Washington, D.C. prosecutor’s office, taking photographs in his spare time and pursuing a passion he’d had since a child when his mother gave him his first camera. Evidence of his unencumbered approach to his subjects that day resound in his images—a cache of photographs portraying a plurality of faces and brimmed with individual stories and portrayals. Terry is bearing witness, capturing decisive moments that encapsulate the energy of the moment. His photographs force the viewer to see these men as whole people, not as the tropes and stereotypes typically used to characterize black men. Looking back 25 years later, Terry’s nuanced documentation feels even more necessary and urgent in the wake of today’s racial reckoning following the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and countless other victims of police brutality.

“I really wanted to get a cross-section of the participants,” he says. “Old and young participants. Straight and gay. Fathers and sons. People of different religious affiliations. People from different regions of the country. [I wanted to] just show us in our most natural state.”

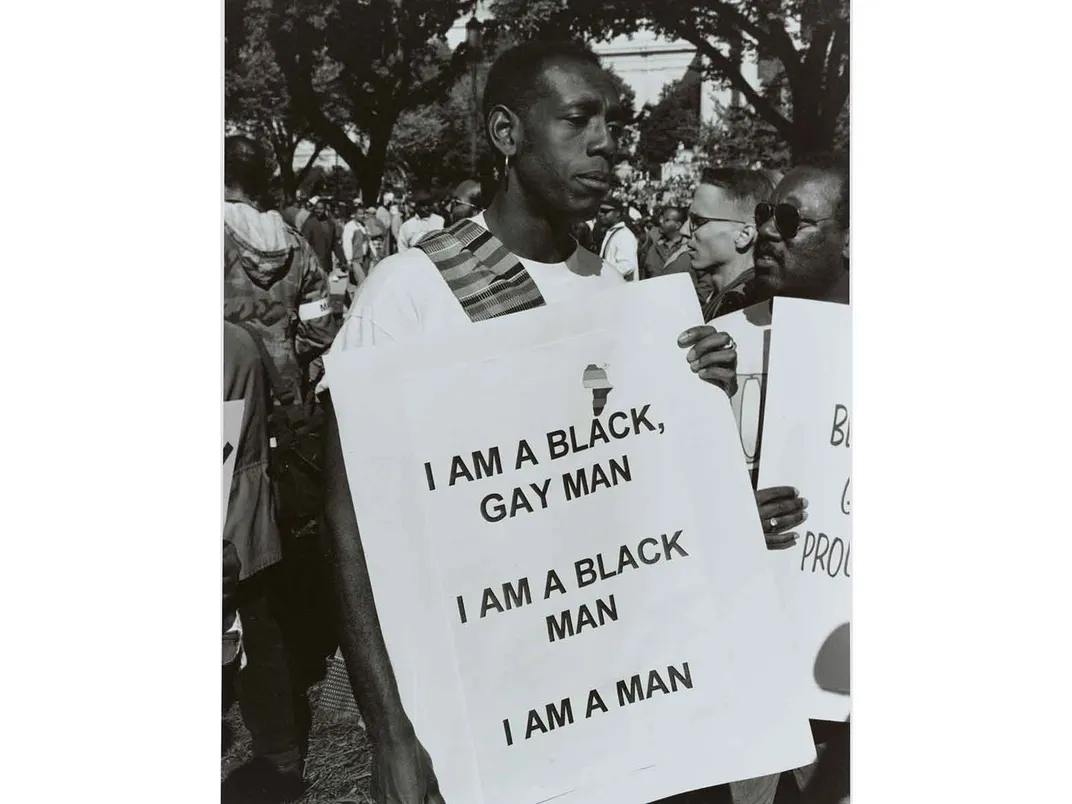

In the photograph, I am a Man, Derek Charles Livingston holds a sign saying, “I Am A Black, Gay Man. I Am A Black Man. I Am A Man,” recalling another watershed moment in the civil rights movement—a photograph taken during the 1968 Sanitation Worker’s Strike depicting a parade of men carrying signs emblazoned with the words “I Am A Man.”

Livingston’s face is solemn, distant. His eyes avoid the viewer, registering, perhaps, a weariness of oppression, a feeling of being unheard. Many mainstream narratives of black masculinity can focus on homophobia, violence and laziness, even if these personality traits are stereotypical or grossly inaccurate. Terry’s photograph, on the other hand, tells a different story about a queer black man affirming his identity.

“Why did he take that photo?” asks Aaron Bryant, a curator at the African American History Museum. “Why was it important for him to show? Well, as a historian I think it was important. We generally buy into the whole idea of heteronormativity when defining the black male identity, and the Million Man March was defined that way, as well, at least in the cultural imagination. But when [Rod Terry] took that picture, there were actually groups of gay men who were there, out in the crowd who were part of that movement as well, and you never hear about that. Rod saw that, and recognized the importance of capturing it.”

In his photograph Dome and Silhouettes, the backs of two unidentifiable men are carefully framed against the U.S. Capitol. Looming overhead is the figure of Lady Freedom at the top of the doom. The composition communicates a sense of deep historical trauma as well as a silent sense of solidarity.

“The reason I think this photograph captures the spirit of the march is because you have a juxtaposition between those two black men, and on the capitol dome you have the freedom statue. The interesting thing about that statue is that it was casted and hoisted up onto dome by slaves,” Terry says.

Later, he continues, speaking about the ironic nature of using slave labor to create a freedom statue. “You have this occasion, the Million Man March, and I’m able to capture two black men standing in front of this statue, the freedom statue, that a slave helped to build. I found it remarkable.”

Now an author of such acclaimed works as Hope Chest: A Treasure of Spiritual Keepsakes and the award-winning Brother’s Keeper: Words of Inspiration for African American Men and One Million Strong, Terry is pleased his images are housed in a permanent collection for future generations.

“It’s really about representing the voices of the people who were there and representing the perspectives . . . and the experiences,” Bryant says when reflecting on the importance of having the Terry’s photographs in the Smithsonian’s collection. “We’re really about preserving what he experienced. These photographs represent his voice and his experience and the experiences of the people he captured in the photographs. And so we’re committed to preserving their experiences. That’s the national treasure for us. Their experience is the national treasure.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)