Who Were the Six Native American Chiefs in Teddy Roosevelt’s Inaugural Parade?

Another inauguration, another opportunity to learn more about the men whose presence shocked the country

![]()

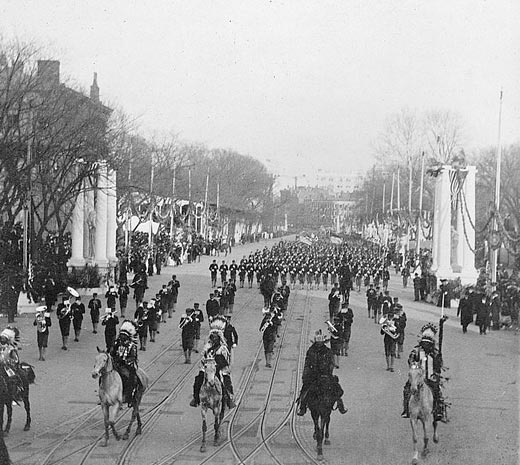

Marching in the parade. Courtesy of the National Museum of American Indian/LOC

Among the 35,000 people who participated in Theodore Roosevelt’s inaugural parade on March 4, 1905, were six men on horseback wearing elaborate headdresses. Each was an Indian chief and each had at one time or another been at odds with the American government. They were Quanah Parker of the Comanche, Buckskin Charlie from the Ute, Hollow Horn Bear and American Horse of the Sioux, Little Plume from the Blackfeet and the Apache warrior Geronimo. As they rode through the streets of Washington on horseback, despite criticism, Roosevelt applauded and waved his hat in appreciation. They are the subject of the American Indian Museum’s exhibit, “A Century Ago: They Came as Sovereign Leaders.”

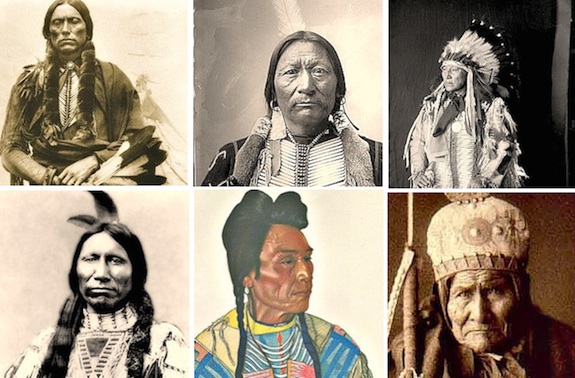

The six chiefs who rode in Roosevelt’s inaugural parade each had their own objectives to accomplish. Courtesy of the American Indian Museum

“In the years before the 1905 procession, tensions grew between Native peoples and white settlers over rights to natural resources,” writes Jesse Rhodes, covering the exhibit when it was last on view in 2009. Each chief had accepted the invitation, hoping to make progress on crucial negotiations with the president and advocate for the welfare of their people.

The article explains, “‘The driving idea about Native Americans,’ says Jose Barreiro, a curator at the National Museum of the American Indian, ‘was represented by Colonel Pratt who was the head of the Carlisle Indian School and his famous phrase, ‘Kill the Indian, save the man,’ meaning take the culture out of the Indian.’”

The presence of the six men prompted a member of the inaugural committee to ask Roosevelt, “Why did you select Geronimo to march in your parade, Mr. President? He is the greatest single-handed murderer in American history?” Roosevelt replied, “I wanted to give the people a good show.”

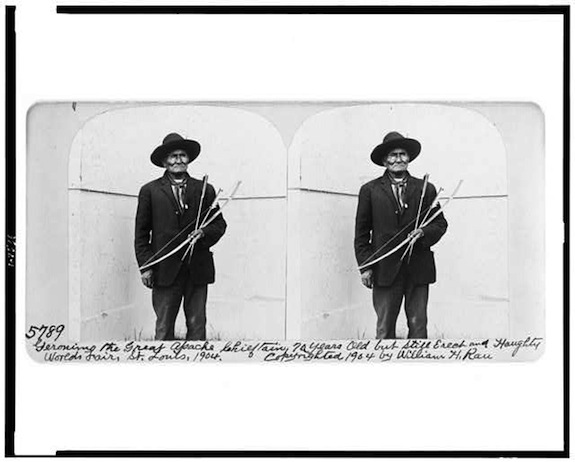

Geronimo at the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis, which marked the centennial of the Louisiana Purchase. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

The eldest of the six men, Goyahkla, or Geronimo as he was nicknamed, was best known to the American public for his role in the Apache wars but he gained another sort of stardom after his eventual surrender in 1886. Exiled to Fort Sill, Oklahoma with his followers, Geronimo began making appearances at national events, including the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis. Often receiving payments for such appearances, he even sold signed pictures of himself, according to the Oklahoma Historical Society.

The six men line up before the parade begins. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Seen as an opportunity to raise the profile of Indians in American society and gain an audience with the leader of the country, the inaugural parade in 1905 also marked a low point for the chief. After receiving a roar of applause during the parade, Geronimo later visited with the president in his office and pleaded with Roosevelt to let his people go back to their home in Arizona, according to Robert Utley’s new biography Geronimo. “The ropes have been on my hands for many years and we want to go back to our home,” he told the president. But Roosevelt responded through an interpreter, “When you lived in Arizona, you had a bad heart and killed many of my people. . . We will have to wait and see how you act.”

In the Inaugural parade, Geronimo proudly wore a beaded headdress. Photo courtesy of the American Indian Museum

Geronimo began to object but he was silenced by the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Francis Ellington Leupp, who led him out of the president’s office. “I did not finish what I wished to say,” he told Leupp, according to an article in the New York Tribune.

Leupp insisted that Geronimo was “better off” in Oklahoma. And though he patronizingly described the chief as an example of a “good Indian,” he remained unsympathetic to his requests.

When Geronimo died in 1909 he was still in Fort Sill. In his obituary, the New York Times wrote, “Geronimo gained a reputation for cruelty and cunning never surpassed by that of any other American Indian chief.”

There was no mention of his role in the recent inauguration or the dedication in his 1906 autobiography which read, “Because he has given me permission to tell my story; because he has read that story and knows I try to speak the truth; because I believe that he is fair-minded and will cause my people to receive justice in the future; and because he is chief of a great people, I dedicate this story of my life to Theodore Roosevelt, President of the United States.”

“A Century Ago: They Came As Sovereign Leaders” was at the American Indian Museum through February 25, 2013.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)