Elizabeth Acevedo Sees Fantastical Beasts Everywhere

The National Book Award winner’s new book delves into matters of family grief and loss

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/73/a9/73a9b9d8-9654-4728-95b7-1167a8d05d78/elizabeth-acevedo.jpg)

Elizabeth Acevedo dreamed of becoming a rapper. Even after discovering her love of performing verse, her work remains rooted in hip-hop. “It didn’t start with poetry,” says the award-winning and best-selling poet and author.

Born and raised in New York City’s Morningside Heights neighborhood, Acevedo has been influenced by music for as long as she can remember. Every Friday night, her Afro-Dominican parents would play boleros—“old torch songs with heartbreaking melodies”—and after they went to sleep, her two brothers turned on the hip-hop.

“I think we sometimes forget that musicians are poets and should be held up just as high,” she says. A selection of her poems was recently published as a part of a collaborative poetry book, Woke: A Young Poet’s Call to Justice, and her novel, Clap When You Land, is just out today. She believes that being a YA author is about supporting the younger generation by listening to what they have to say—“I want to listen as much as I’m talking.”

Acevedo’s creative voice was also molded by the community she grew up in. Dominican culture and the experience of being a first-generation immigrant feature heavily in her work. “My neighborhood, ‘Harlem Adjacent’ as I like to call it, was predominantly black and Latino. People from all over the Caribbean. I grew up in a place that was very stratified and very clear. Go one, two avenues over from our house, and its Riverside Drive and Columbia professors—a very different socioeconomic class. It’s New York City and this huge melting pot. I grew up with an understanding of difference, and the haves and have-nots.”

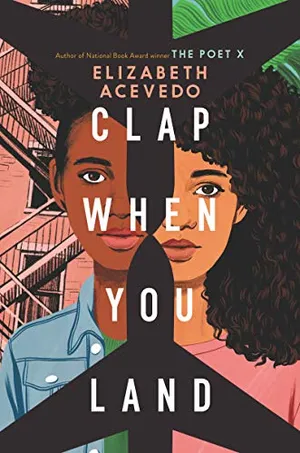

Clap When You Land

In a novel-in-verse that brims with grief and love, National Book Award-winning and New York Times bestselling author Elizabeth Acevedo writes about the devastation of loss, the difficulty of forgiveness and the bittersweet bonds that shape our lives.

As with many children of immigrants, Acevedo found herself translating English for her parents. Early on, she recognized the inherent power of language. In particular, she saw poetry’s ability to speak to dark, complex themes. Through her work, she explores monsters found both in the everyday world and in mythology. At her first poetry slam when she was only 14 years old, Acevedo recalls performing a poem about sexual assault. At the time, there had been several serial rapes in her area, and she wished to address the fear that pervaded her community.

What inspires Acevedo more than anything else are uncelebrated heroes. While pursuing an MFA in creative writing from the University of Maryland, she realized she wished to dedicate her writing to this idea. She felt somewhat isolated, as the only student in the program of African descent, of an immigrant background, and from a large city.

When her professor asked everyone in the class to choose an animal to praise in an ode and explain why, Acevedo chose rats. “If you grow up in any major city, you know rats.”

Her professor laughed and said: “Rats aren’t noble enough creatures for a poem.”

Those words struck her. She knew he was not trying to be malicious, but the idea that only certain symbols deserve to be written about did not sit well. She rejected these stereotypes in the literary arts, believing that writing should not conform to a privileged concept of nobility.

“I decided to write the rat from that moment forward.”

Because you are not the admired nightingale.

Because you are not the noble doe.

Because you are not the blackbird,

picturesque ermine, armadillo, or bat.

They've been written, and I don't know their song

the way I know your scuttling between walls.

The scent of your collapsed corpse bloating

beneath floorboards. Your frantic squeals

as you wrestle your own fur from glue traps.

…

You raise yourself sharp fanged, clawed, scarred,

patched dark—because of this alone they should

love you. So, when they tell you to crawl home

take your gutter, your dirt coat, your underbelly that

scrapes against street, concrete, squeak and filth this

page, Rat. —Excerpt from “For the Poet Who Told Me Rats Aren’t Noble Enough Creatures for a Poem”

Acevedo believes that her community’s stories go unrepresented in what the art world considers “high literature” because critics believe they have little “cultural currency.” She resolved to write poems and prose that empower members of her ethnic background by telling their stories. So far, her novels have been geared to a young adult audience because she knows firsthand how important it is to have access to books that feature people like yourself during your formative years.

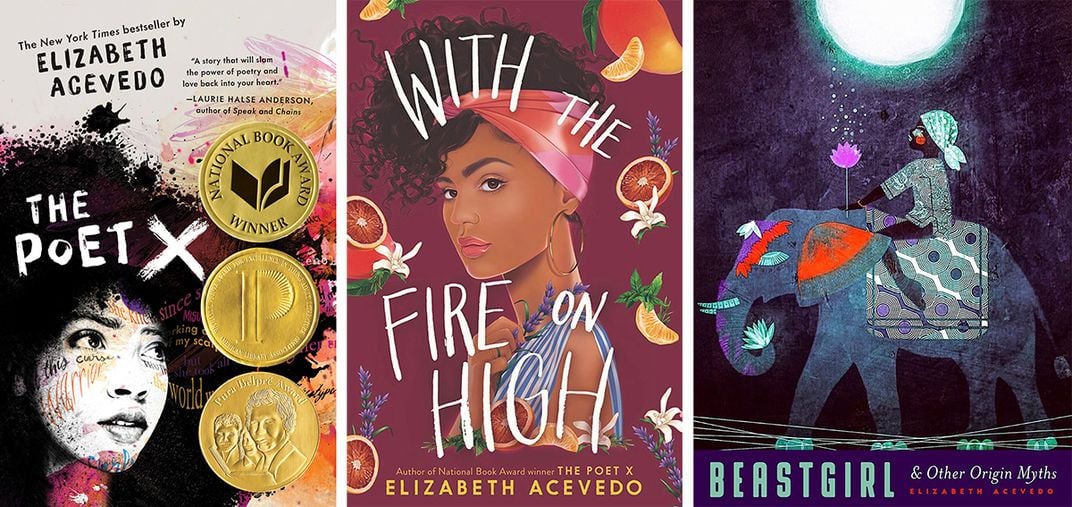

In her award-winning debut novel, The Poet X, a New York Times bestseller, the protagonist is a young Afro-Latina from Harlem who is trying to find her voice as both a slam poet and a woman. Her second critically acclaimed novel, With the Fire on High, also revolves around an Afro-Latina—this time, an aspiring chef and teen mother in Philadelphia.

“In young adult fiction,” she points out, “there is a small canon of stories of young women trying to decide whether or not they can keep a child. What about after?”

Although there is a significant amount of crossover, Acevedo considers the themes she explores in her fiction different from those in her poetry. Through poetry, she can address culture in a broader, less tangible way: “Dominican culture is a storytelling one with lots of superstitions,” she says.

Her first poetry anthology, Beastgirl & Other Origin Myths, includes a practical-sounding poem entitled simply “Dominican Superstitions.” One stanza reads, “For ghosts that won’t leave: use frankincense/ Conduct a rosary circle. Lead them to a tree that guards gold.”

Another poem is a tribute to a story that Acevedo’s mother would tell her about the brujas (witches) who allegedly sat on people’s houses, ears pressed to the zinc walls, spying for the former Dominican Republic president, the tyrannical dictator Rafael Trujillo.

After Mami thought I was asleep, I wondered about the brujas;

what did they do when Trujillo was assassinated?

…

Did the brujas go underground,

take normal jobs selling boletos and eggs

at the local colmado, and braiding hair

on the tourist beaches?

…

where they could forget

the winged words that once drifted up to their ears,

that made them heavy and rush-filled with blood?—Excerpt from “The Dictator’s Brujas or Why I Didn’t Grow Up with Disney”

“I’ve been fascinated by witches my whole life,” she says. For her, mythology is more than a pantheon of supernatural beings. “It’s all those stories you heard growing up that made you into the figure you are.” These tales help people grapple with their place in the world because, in her words, they “explain the unexplainable.”

Studying the rich panoply of Dominican folklore to use in her work allows Acevedo to ask deeper questions. She seeks to learn from these myths and legends because, she believes, the figures who populate them are never forgotten. As a part of a culture where “folklore weaves seamlessly into the everyday,” these stories become a part of a person’s makeup.

In her poem “The True Story of La Negra. A Bio-Myth,” Acevedo delves into the idea of the anthology’s titular beastgirl, a symbol of cultural weight for Afro-Dominicans, trapped inside her human descendants:

This is where she will end:

enveloped in candlewax. Scratched & caught

beneath your nails.—Excerpt from “The True Story of La Negra. A Bio-Myth”

One myth that particularly captivates Acevedo is La Ciguapa. The best-known figure in Dominican lore, La Ciguapa lives at the heart of the rural mountainous region of the island nation. Some say her skin is blue; others say pale brown. She has large, dark eyes and her long, lustrous hair is her sole garment. She cannot speak save for a throaty whisper. While some say she is timid and nymph-like, others say she hypnotizes wandering men with her eyes, seduces them, and destroys them, leaving not a trace behind.

Nevertheless, what makes La Ciguapa unique are her backward-facing feet, which make it impossible to know where she is coming from or going to. Only by the light of the full moon and with the aid of a black and white polydactyl cinqueño dog can she be hunted down.

What especially intrigued Acevedo was the panic surrounding La Ciguapa. “She was the reason you didn’t go off into the mountains. People in the capital would say that it was a campesino [farmer] thing, but my mother remembers how people would say they had seen her. La Ciguapa is alive to this day, and no one is sure where she comes from.”

Some attribute her origin to one of the Taíno natives who fled to the mountains to escape Christopher Columbus. Others believe she was enslaved and escaped. Others claim she predates Columbus altogether. “The next question for me is why, why would we make her a seducer of men?” Acevedo says. “What does that say about patriarchy and misogyny and oppression?”

They say La Ciguapa was born on the peak of El Pico Duarte.

Balled up for centuries beneath the rocks

she sprang out red, covered in boils, dried off black

and the first thing she smelled was her burning hair.

…

Her backwards-facing feet were no mistake, they say,

she was never meant to be found, followed—

an unseeable creature of crane legs, saltwater crocodile scales,

long beak of a parrot no music sings forth from.

…

They say. They say. They say. Tuh, I’m lying. No one says. Who tells

her story anymore? She has no mother, La Ciguapa, and no children,

certainly not her people’s tongues. We who have forgotten all our sacred

monsters.—Excerpt from “La Ciguapa”

Acevedo is moved by history and uses folklore as a way to decode it. Many of the stories she wants to investigate—those of Indigenous tribes before and during colonization as well as the many slave rebellions preceding the Haitian Revolution—are not well documented. Folklore, however, is a valuable tool because “the feeling of mythology is true.”

When studying slave rebellions, she asks, “What was the role of magic?” These stories, characters, and monsters are raw reflections of people confronting the often-savage reality of their time. Questioning the meaning behind folklore yields hauntingly surreal poems, such as one dedicated to the island of Hispaniola, “La Santa Maria,” where Acevedo creates the image of hundreds of thousands of deceased Africans setting fire to their slave ships on the Atlantic Ocean floor.

In an upcoming poetry anthology, Acevedo examines what would happen if mythological figures were thrust into our world. A series of poems will revolve around the classical figure of Medusa, a monster from ancient Greece, who possessed a mane of snakes and a gaze that turned her victims to stone.

“She is summoned to Harlem in New York City by a Negra who’s like, ‘I want you to teach me how to be a monster. I want you to teach me how to survive,’” Acevedo says, describing how she wanted to drop the characters of common myths into new communities and see how they hold up.

In one poem, La Negra takes Medusa to a hair salon to get her snakes done. “There’s a bizarreness in magic, but when you don’t have examples of people like you joyously thriving, what do you latch onto? Who can make you feel bigger than what you feel like you are?”

Monique-Marie Cummings, an intern at the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, will join Dartmouth College’s class of 2024 in September.

A version of this article originally appeared in the online magazine of the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.