Poet and Musician Patti Smith’s Endless Search in Art and Life

The National Portrait Gallery’s senior historian David Ward takes a look at the rock ‘n’ roll legend’s new memoir

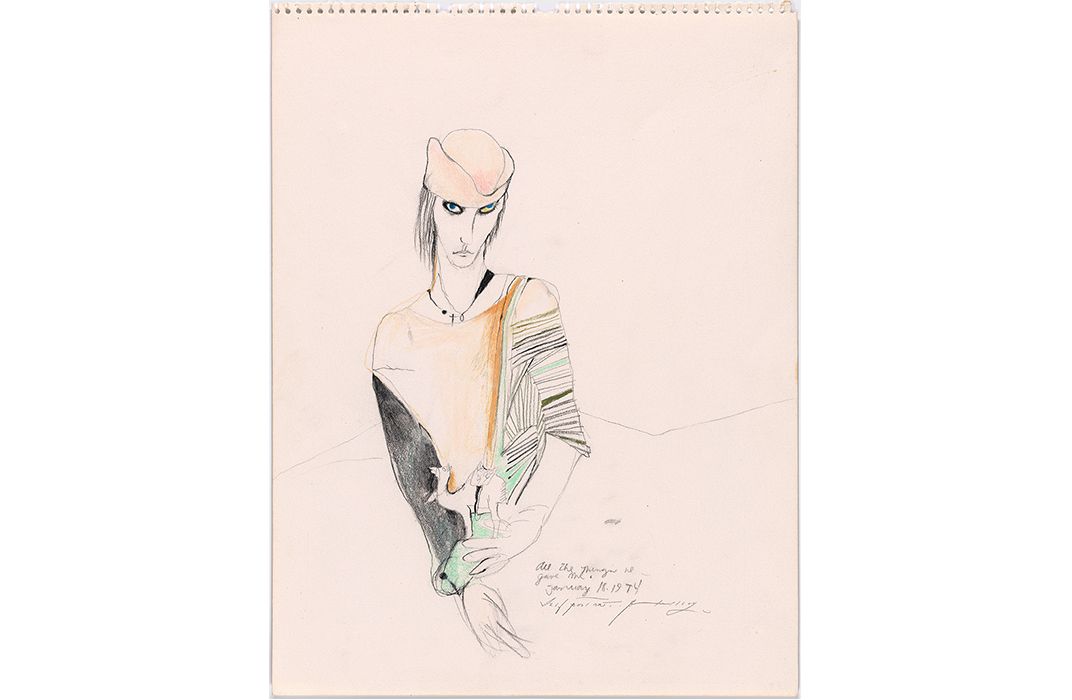

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0c/2f/0c2f7bcb-255d-45de-a45e-df9afbe3dc39/exhcl39web.jpg)

Patti Smith, rock ‘n’ roll legend and writer, has a word game she plays, especially when she can’t sleep. She picks a letter of the alphabet and thinks of as many words as she can that begin with that letter—saying them without pause.

Sometimes she just allows the initial letter to pop into her head. Other times, she finds it by using her finger like a dowsing rod to point to a key on her MacBook. So “V. Venus Verdi Violet Vanessa villain vector valor vitamin vestige vortex vault vine virus. . .” In her affecting new memoir M Train she helpfully provides a list of M words that trip delightfully from the tongue: “Madrigal minuet master monster maestro mayhem mercy mother marshmallow . . .mind.”

The letter M hints at the memoir’s themes—she is fond of Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita; she seeks mercy; her mother is important to her. . .

But it would be an error to try to reduce her intentions to a single interpretive clue to “solve” the case; it’s too reductive to Smith’s copious journeying to reduce the M in M Train to “mind,” for instance. Instead, we need to take Smith at her word or words in a book that hopscotches (Smith uses the childhood sidewalk game as an analogy for her word game) from place to place and time to time.

The actual M train on the New York City subway is a red herring: it traces a tight little circuit, including through lower Manhattan (another M!), Brooklyn and Queens that doesn’t really connect with the geography of Smith’s life. Except a subway makes many stops as does her M Train. And there’s a famous blues song “Mystery Train,” where the train is a stand in for fate and death, subjects of interest to Patti Smith. And there’s a Jim Jarmusch movie of the same title in which a Japanese couple arrive in Memphis on a spiritual quest, just as Smith will go to Japan on a similar errand.

So. . . once you start to play Smith’s word games the implications multiply and collide with one another in ways that are unexpected and illuminating—illuminating in particular of the consciousness of one of our most original artists.

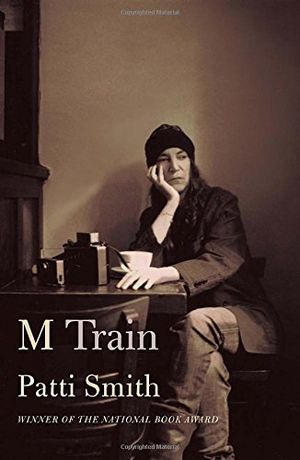

M Train is the successor to Smith’s first book, the award-winning, bestseller Just Kids (2010), which is centered on her relationship with the artist Robert Mapplethorpe and describes her evolving consciousness as she moves to New York in the late 1960s and becomes an adult. For an artist known for the ferocious attack of her rock ‘n’ roll performances as well as in her poetry, Just Kids was a surprisingly gentle elegy to the past in a way that was romantic but never sentimental. Things could have been the way Smith describes them, and although a reader might be skeptical, her version of the events works because she was such a consummate stylist. The structure of Just Kids was circular, beginning and ending with images of the sleeping Mapplethorpe and the circularity of that “plot” was mirrored in Smith’s meditations on circles or cycles as loosely spiritual motifs in her life.

M Train is plotted differently. It consists of short episodic chapters on a series of incidents or events that pique Smith’s interests. Eventually the subway analogy derails—there are no tracks for Smith (and the reader) to follow. She’s making up the journey and the schedule as she goes along.

Yet the word game emerges as the organizing principle. To stay with another M: the band MC5—short for Motor City 5, formed by Patti Smith’s husband Fred Sonic Smith. This is as much Sonic Smith’s book as Just Kids was Robert Mapplethorpe’s.

Patti Smith describes how she fell in love with Fred Smith and abandoned her plan to open a small café in New York to move to Michigan with him. She was bowled over by him.

My yearning for him permeated everything – my poems, my songs my heart.

We endured a parallel existence. . .brief rendezvous that always ended in wrenching separations. Just as I was mapping out where to install a sink and coffee machine, Fred implored me to come and live with him in Detroit.

They married and had two children before his tragic and very early death at 44. The picture that Smith draws of her husband and artistic partner does not focus on his music, but on his quiet competence, especially when he gets them out of a scrape in French Guiana where they had gone, at Patti’s urging, on a pilgrimage to the infamous prison that might have housed the French writer and criminal Jean Genet.

If Fred Smith anchored her for a time, that anchor is now gone. Smith’s life, as she describes it is a series of inward and actual journeyings, in which she seeks to find a place to stay.

Like that original dream to set up a café in New York, she has her table and chair in her favored “Café Ino.” It is, to use a Hemingway word derived from bullfighting, her querencia–the safe spot that the bull finds in the ring. (When the Café closes, she is given “her” table and chair to take home.

She has her house and bedroom and her three cats in lower Manhattan. The bed is a refuge and a workplace.

“I have a fine desk but I prefer to work from my bed, as if I’m a convalescent in a Robert Louis Stevenson poem. An optimistic zombie propped by pillows, producing pages of somnamublistic fruit. . .”

She is drawn to other abodes, like Frida Kahlo’s famous Casa Azul in Mexico City. She impulsively buys a rundown beachfront bungalow in Far Rockaway that miraculously survives hurricane Sandy, but in the book has not yet been made fit to live in. It remains a dream, a place you can’t stay. Smith is always looking for connections in places or things. She visits graves in Japan and turns ordinary objects, like a table used by Goethe, into a time traveling portal.

She uses a Polaroid camera to take a photo of the table and puts it above her desk back home:

“Despite its simplicity I thought it innately powerful, a conduit transporting me back to Jena. . . I was certain that if two friends laid their hands upon it. . .it would be possible for them to be enveloped in the atmosphere of Schiller in his twilight, and Goethe in his prime.”

Smith likes the outdated Polaroid because of the tactile sense of unpeeling the developing print after it’s ejected from the camera, and the ghostly image of the film itself.

There’s a great story about how, on a whim, she went to Cambridge University to find the room where the philosophers Wittgenstein and Karl Popper had a famous fistfight.

She breaks away from another trip to continental Europe with a swerve to London where she holes up in a hotel and streams videos of her favorite detective series. Smith ruefully admits that she would probably make a bad detective, but she shares the fictional contemporary detective’s drive not so much to solve the crime as to uncover the mystery—a mystery that usually connects the present to the past.

Throughout this restless search, there is a subtext of loss. Finding is compensation for losing. Smith ruefully admits to her habit of losing things, not just big things like Robert Mapplethorpe and Fred Sonic Smith, but little things like a treasured book, a coat and other talismans.

Entropy infuses M Train. Smith imagines the “Valley of Lost Things,” a comic trope which is deadly serious. The Valley is not only where all these things, big to small go but also seems to have the power to draw them ineluctably away from us to disappear.

“Why is it that we lose the things we love, and things cavalier cling to us and will be the measure of our worth after we’re gone.”

Finding a place in the world, a place of rest, a place where love lasts, is Patti Smith’s dream and it is one that forever will elude her. Her life is in the searching.

The poet John Ashbery has a great line, using another M word: “The mooring of starting out.” Patti Smith’s restless journeying is where she is at home.

M Train

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/David_Ward_NPG1605.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/David_Ward_NPG1605.jpg)