Poetry Matters: In Baseball, No Poet Has Yet to Do the Game Justice

Smithsonian historian David Ward umpires the field of poetry, honoring the boys of spring, and calls a strike

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/93/25/9325bea8-607c-4180-b4d1-90d429f2174e/mmoore1-wr.jpg)

Baseball is a game of unpredictable actions occurring within strictly defined guidelines—innings, strikes and outs. It should be perfect for poetry. But there has yet to be a truly great poem about baseball. The desire to be serious is what kills most baseball poems—they’re all metaphor and have none of the spontaneous joy that went into, say, John Fogarty’s pop song “Center Field.”

Put me in coach, I’m ready to play.

“April is the cruelest month,” is one of the most famous lines in poetry, but it is one that only makes sense in the post-apocalyptic world of T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land.” For the rest of us, clinging to hope, warm weather and the eternal prospect of new beginnings, April is not cruel at all, but welcomed. And in America, it’s welcomed because of baseball. Indeed baseball and spring, the meaning of one spills into the other in a mutually reinforcing bond of associations between the game and rebirth. It is the time when the white chill of snow is replaced by the diamond’s green growth of grass.

But this renewal is specific, even nationalistic, and uniquely American. Baseball speaks to the our country’s character and experience. In particular, the sport is rooted in special connection that Americans have with the land; an encounter with nature formed a particular type of person—and a particular type of democracy and culture.

The founding myth about baseball—that General Abner Doubleday “invented” the game in and around Cooperstown, New York, as an activity for his troops—is historically inaccurate, but satisfying nonetheless. Where better for baseball to have been created than in the sylvan woodlands of upstate New York, home of James Fenimore Cooper’s frontier heroes, Leatherstocking and Natty Bumppo? If Cooperstown is a myth, it is one that endures because the idea of America’s game being born out of the land confirms the specialness, not just of the game, but of the people the game represents. Yet it is impossible to disentangle baseball from its myths; and it seems uncanny that the first professional baseball game ever played actually occurred in urban Hoboken, New Jersey, at a place called “Elysian Fields,” Uncanny, because in Greek mythology, these are the fields where the gods and virtuous disported after they had passed on. Is this heaven?

Recall a certain magical ballfield built in Iowa cornfield, where the old time gods of baseball came out to play? The 1982 novel Shoeless Joe by W.P. Kinsella, later adapted into the 1989 film Field of Dreams, starring Kevin Costner, certainly paid homage to that Greek myth.

The virtuous and heroic in baseball is the subject of much non-fiction journalism of course, from beat writing to one of the greatest essays ever penned, John Updike’s eulogy to Ted Williams, “the best old hitter of the century.” Inevitably it is also the subject of both literary fiction and poetry. Poetry is especially suited to expressing the mythic attractions of the game. And back when poetry was more a part of regular conversation, sportswriters and newspapermen used verse to comment on the game. In 1910, Franklin P. Adams penned his famous tribute to the Cubs’ double play combination, “Tinker to Evers to Chance/A trio of bear cubs fleeter then birds.” And probably the single most well-known poem is Ernest Thayer’s comic 1888 ballad of mighty “Casey at the Bat.” Fiction inevitably requires the author to get down and dirty in the rough and tumble of a difficult sport played (mostly) by young men, full of aggression and testosterone–not always a pretty sight.

But poetry creates just the right tone to convey the larger meaning of the game, if not always the game itself. There are not many poems from the participant’s point of view. With a poem comes the almost automatic assumption that the poet will see through the baseball game to something else, frequently the restoration of some lost unity or state of grace. Poetic baseball creates an elegy in which something lost can be either regained or at least properly mourned.

In 1910 the great sportswriter Grantland Rice made just that point in his “Game Called,” that as the players and the crowd exit the stadium: “But through the night there shines the light/home beyond the silent hill.”

In his comic riff on sports, the comedian George Carlin croons that in baseball “you go home.” There are a lot of poems in which families re-connect, sometimes successfully, by watching baseball or by having fathers teach sons how to play.

For modernist poets—the heirs to Eliot—baseball was generally ignored because it was too associated with a romantic, or even sentimental, view of life. Modernism was nothing, but hard headed and it was difficult to find a place for games. William Carlos Williams, in his 1923 poem “The Crowd at the Ball Game,” delights in the game, precisely because it’s a time out from the hum-drum grind of daily work.

The crowd at the ball game

is moved uniformly

by a spirit of uselessness

which delights them

And this purposelessness has a point, “all to no end save beauty/the eternal.” Williams is mostly after the relationship between crowd and individual, the game is not really the thing.

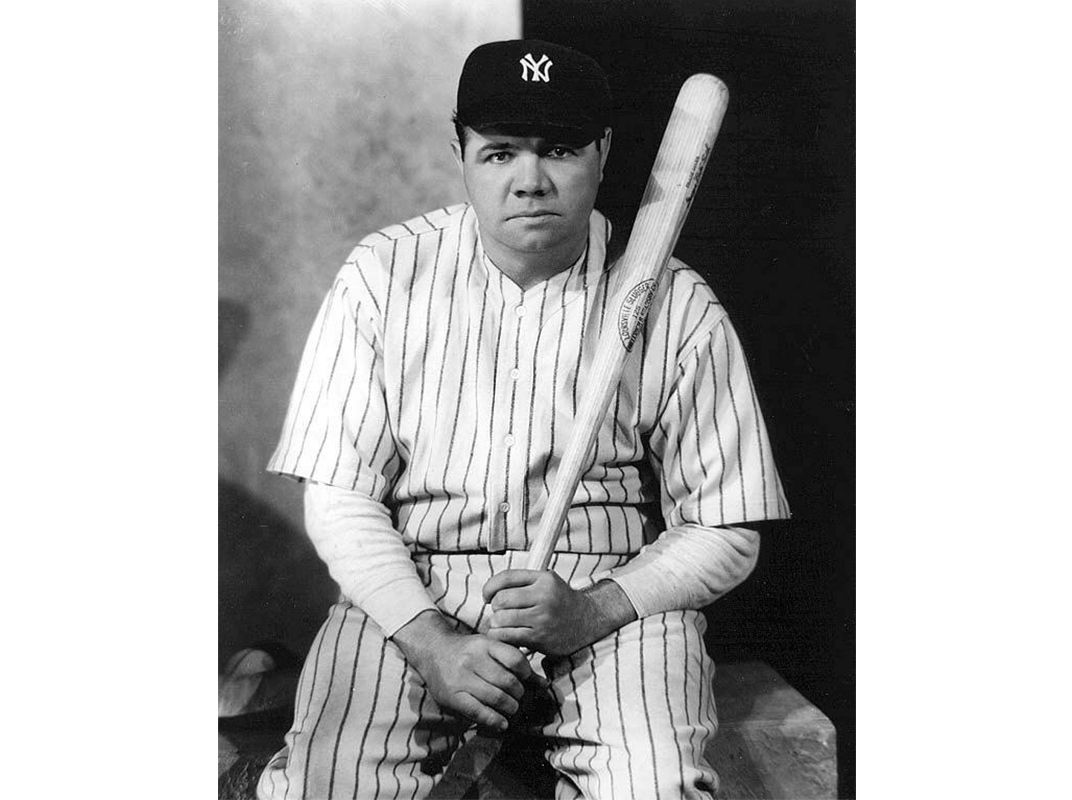

The great Marianne Moore got something of a reputation in the popular press for actually being a fan of baseball, and in 1968 threw out the first pitch at Yankee Stadium (above). In fact she was often seen in stands, taking in a game and some of her poems reference bats and balls. She talked about creativity more expansively in “Baseball and Writing:”

Fanaticism? No. Writing is exciting

and baseball is like writing.

You can never tell with either

how it will go

or what you will do;

generating excitement

This gets closer to the flow experience of the game itself rather than just describing it but the poem then breaks down into a not very good roll-call of Yankee players from the early ‘60s. Baseball always crops up enough to make it interesting to see how poets have used it. May Swenson turned baseball into an amusing puzzle and word play game based on romance and courtship:

Bat waits

for ball

to mate.

Ball hates

to take bat’s

bait. Ball

flirts, bat’s

late, don’t

keep the date.

And at the end, inevitably, everyone heads home. The Beat Poet Gregory Corso has a typically hallucinatory encounter with Ted Williams “In the Dream of the Baseball Star” in which Williams unaccountably is unable to hit a single pitch and “The umpire dressed in strange attire/thundered his judgment: YOU’RE OUT!”

Fellow beat Lawrence Ferlinghetti invoked baseball to make a civil rights point.

Watching baseball, sitting in the sun, eating popcorn,

reading Ezra Pound,

and wishing that Juan Marichal would hit a hole right through the

Anglo-Saxon tradition in the first Canto

and demolish the barbarian invaders

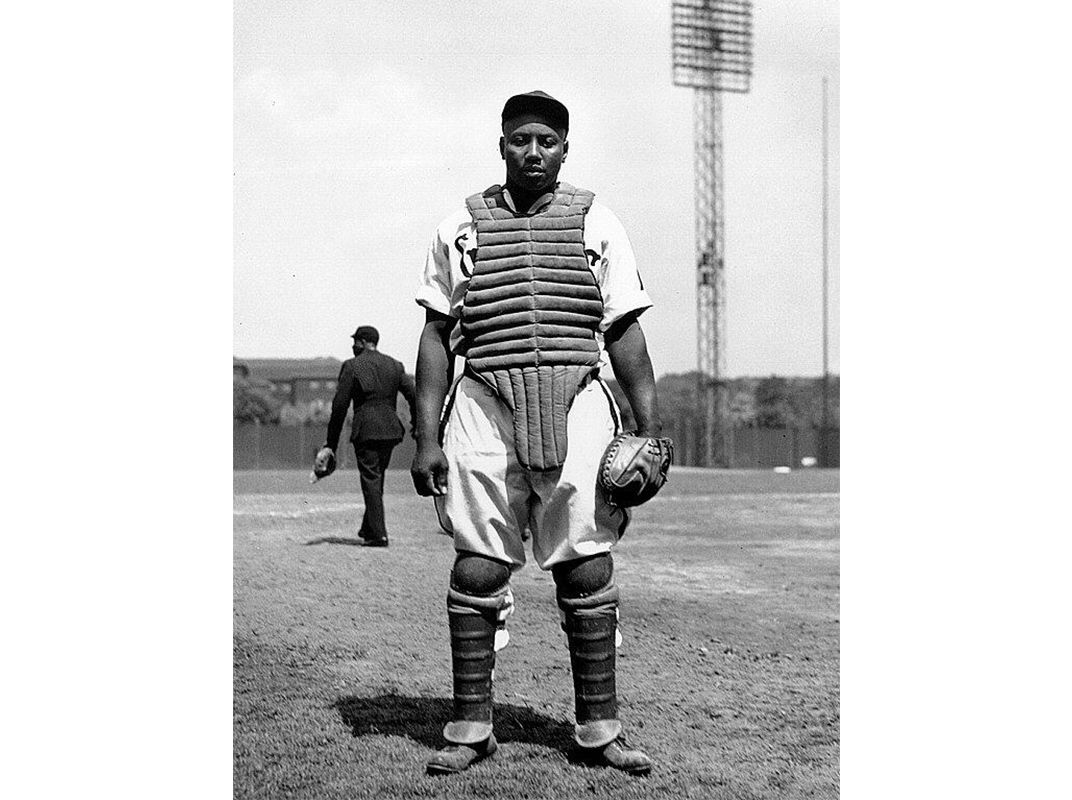

You can sense in the shift from the game to Ezra Pound, the poet’s uneasiness with the game itself and his eagerness to move from the physical to the intellectual. When the body appears in a baseball poem it is the body of the aging poet, as in Donald Hall’s extended, very well done, but extremely depressing linkage of innings going by with aging—and death. Maybe baseball poems will always be troubled with an excess of seriousness; perhaps we’ve become too rooted in the mythology of baseball and character to treat it on its own terms. Alternate takes by African Americans, like Quincy Troupe’s “Poem for My Father” about the impact of the Negro leagues and the prowess of such players as Cool Papa Bell, give another angle on the tradition. Further such outsider views, especially from the point of view of women who are not either adoring spectators or “Baseball Annies”, would be welcome as well.

As with a new season, hope springs eternal not just that a new season is starting but that someday some poet will give baseball the kind of relaxed attention that does the sport justice. It really is remarkable that baseball, which occupies such a large part of our culture and history, remains in the view of this critic, so inadequately treated by our writers and poets.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/David_Ward_NPG1605.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/David_Ward_NPG1605.jpg)