Poetry Matters: Lessons From America’s First Inaugural Poet

Introducing a new monthly poetry column, just in time to offer inaugural poet Richard Blanco some advice from Robert Frost

![]()

In this week of the Presidential Inauguration, it must be said that poetry serves another function when deployed in public: it is classy, it adds tone and the aura of high-minded literary prestige. This is where poetry gets into trouble: when it gets stuffy, pompous, and stiff.

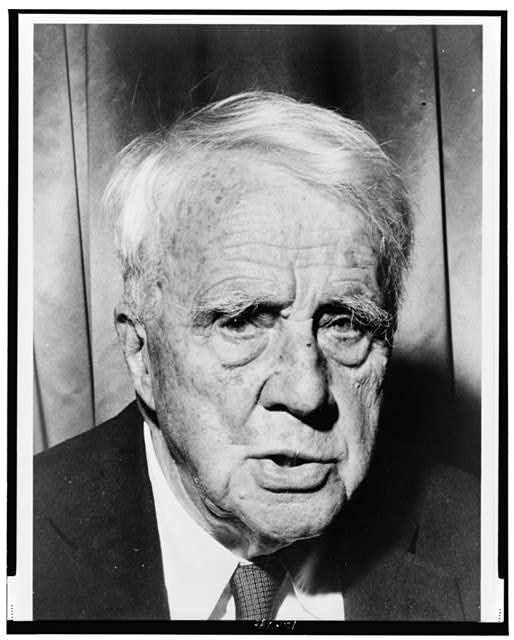

Robert Frost was the first poet included in an inauguration when he spoke at John F. Kennedy’s ceremony. Photo by Walter Albertin, 1961. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

All of these characteristics, the Inauguration has in spades. Inaugurations have gradually gotten bigger and more complicated over time. Certainly, we are far from the day when Jefferson walked over to the Capital from his boarding house, was sworn in, and then walked back to have lunch with his roommates at the communal table. My recollection is that the ceremonies used to be fairly simple, followed by a parade. Now the ceremony itself is lengthy and studded with musical interludes, prayers and invocations, and an inaugural poem—as well as the parade. It’s not clear that the elaborateness of the inaugural ceremony is an improvement over brisk efficiency. The inauguration, which is now an all-day event, tends to bring out the kind of stiff pomposity, both physical and rhetorical, that Americans mock in other areas; the solemn tones of the newscasters with their nuggets of “history.” Inaugural addresses are nearly always forgettable let-downs because the rhetoric is pitched too high as the speaker competes with some ideal notion of “posterity.” Who remembers President Clinton’s awkward rhetorical trope: “We must force the spring,” an admonition that puzzled analysts finally decided was horticultural not hydraulic. One suspects that presidents and their speechwriters are paralyzed by the example of Lincoln and his two majestic Inaugurals.

President Clinton brought back the inaugural poem perhaps seeking a connection with his youth as well as the ideals he hoped to embody since it was President Kennedy’s inaugural that saw perhaps the most famous example of public poetry in American history. Famously, the 86-year-old Robert Frost, a rock-ribbed Rebublican, agreed to read. A flinty, self-reliant New Englander, the poet had been beguiled by the attractive figure of the young Bostonian Democrat. Kennedy, shrewdly courted the old bard—undoubtedly America’s most famous poet—and convinced Frost, against his better judgment, to compose a poem to read at the swearing in. Frost, battening on to the Kennedy theme of a new generation coming to power, struggled to produce an enormous and bombastic piece on the “new Augustan age.” He was still writing the night before the ceremony.

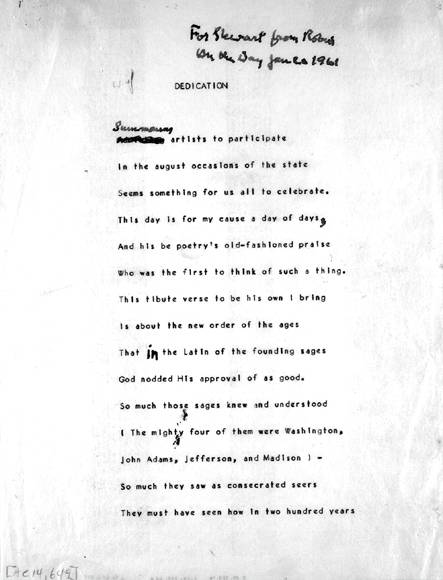

Frost’s inaugural poem, including his edits. He was unable to actually read it at the inauguration. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Amazingly, Frost was unable to deliver the new work: facing east into the noon day, he was blinded by the glare off the snow that had fallen over night and could not read the manuscript of his newly completed ode. So Frost, from memory, recited “The Gift Outright” his paean to America’s foreordained triumphalism: “The land was ours before we were the land’s.”

If the speaking platform had faced west as it does now, all this drama and inadvertent symbolism would have been avoided as Frost could have delivered his giant pudding of a poem. Accidentally, “The Gift Outright” jibed perfectly with JFK’s call to arms and a call to service that troubled only some at the time. But Frost practically was forced to recite “The Gift Outright” once he lost his eyes. It is the only one of his poems that would suit the public needs of the occasion. Imagine the consternation if he had recited the ambiguous and frightening lines of “The Road Not Taken” or the premonition of death in “Stopping by Woods on a Snowing Evening”: “The woods are lovely, dark and deep.” Reading from “Fire and Ice” at that Cold War moment would have gotten the Kennedy Administration off on the wrong foot: “Some say the world will end in fire,/Some say in Ice./From what I’ve tasted of desire,/I hold with those who favor fire.” This could have caused panic if not incomprehension among political observers.

The Inaugural poet does not, then, have an easy task, balancing the public, the private—and above all else the political. President Clinton brought back the inaugural poet tradition with Maya Angelou, whose voice and presence redeemed a poem that is not very good. The others have been competent, nothing more. We will see what the newly announced poet Richard Blanco has to say. He is under tremendous pressure and the news that he is being asked to write three poems, from which the administration’s literary critics will pick one is not reassuring. Kennedy at least trusted his poet to rise to the occasion. Things are rather more carefully stage-managed these days. I wish Mr. Blanco well and remind him to bring sunglasses.

Historian David Ward of the National Portrait Gallery

As both a historian and poet himself, David Ward will contribute monthly musings on his favorite medium. His current show “Poetic Likeness: Modern American Poets” is on view through April 28 at the National Portrait Gallery.

This is, fittingly, Ward’s inaugural post for Around the Mall. This blog, he writes: “has the modest goal—or at least this blogger has the modest intention—of discussing various aspects of American poetry, both contemporary and from past time. Poetry exists in a particularly salient place in the arts because if it is done well it combines opposites: form or structure with personal exuberance, for instance. Above all, it permits the most private feeling to be broadcast to the largest public. Poetry is one of the few ways that Americans permit themselves to show emotion in public, hence people resort to it at funerals – or weddings and other important occasions. Poetry is a way of getting to the nub of the matter; as Emily Dickinson wrote, “After great pain, a formal feeling comes.” There has been a tremendous boom in the number of people who read and write poetry precisely because we see it as a way of opening up ourselves to others in ways that are sanctioned by a tradition that goes back centuries. Among its other dualities, poetry always balances past and present.”