The Stories of Poets, Artists and Cartoon Characters Are All Waiting to Be Discovered in Roy Lichtenstein’s Personal Papers

The Pop artist’s archives, recently donated to the Smithsonian, are soon to be digitized

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8f/e5/8fe5e7c0-625c-47a5-9036-93293d95c64b/roylichtensteininfrontofhispaintingscraig.jpg)

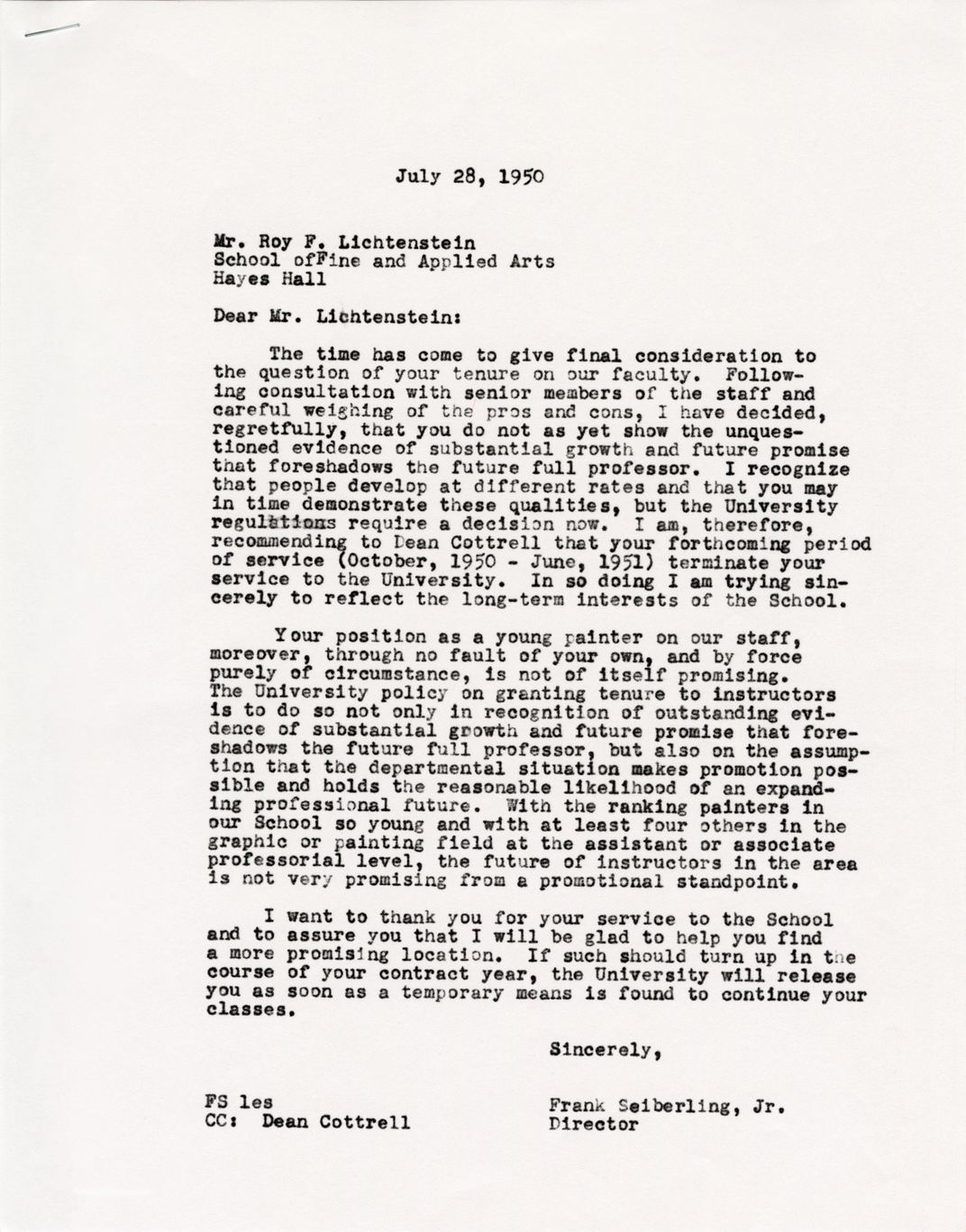

In 1950, a 26-year-old artist named Roy Lichtenstein was teaching at his alma mater, The Ohio State University, when he received a devastating letter. The university had decided not to grant him tenure, it announced, on the grounds that he had failed to demonstrate the “substantial growth and future promise that foreshadows the future full professor.” The school would let him teach for another year, but then he would have to leave.

Lichtenstein was “heartbroken,” says Justin Brancato, head of archives at the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation in New York City. The letter launched a period of years when the artist struggled to find work in Ohio. He decorated storefronts, made models for an architect in Cleveland and worked for his wife’s interior decorating business. In 1957 he finally landed a teaching job in upstate New York, and another position followed in New Jersey. His breakthrough didn’t come until the early 1960s, with the comic-strip paintings that helped launch the Pop movement—and changed the direction of American art.

Art historians hadn’t known about the tenure denial until a Lichtenstein Foundation researcher tracked the letter down at Ohio State, long after the artist’s death. Soon the letter, along with the rest of the foundation’s voluminous archives, will be available to anyone, free of charge, when the foundation donates them to the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art in Washington, D.C. The foundation is funding the digitization of the collection, enabling much of it to be posted online.

Established after the artist died in 1997, the foundation has supported exhibitions, books and research on Lichtenstein and other artists. Now, in donating its archives to the Smithsonian, along with a gift of more than 400 artworks to the Whitney Museum of American Art—both were announced in June 2018—the foundation is beginning the process of shutting itself down.

The transfer may take years, but eventually the Lichtenstein materials will make up the Archives’ “largest single-person” collection, by a wide margin, says Liza Kirwin, deputy director of the Archives of American Art. The materials will join the Archives’ already substantial collections touching on Lichtenstein, including the papers of other artists he knew and of the Castelli Gallery, which represented him for decades. For art historians, the gift’s promise lies not just in its scale and Lichtenstein’s outsize place in 20th-century art, but in the fact that much of the materials will be searchable together online, bringing out connections among them and opening “new avenues for ways of thinking about Roy, his circle, the time,” says Kirwin.

Last October, the foundation promised a further gift of $5 million toward digitizing the Archives’ collections on artists of color and women artists. The Archives has “fantastic collections of African-American artists, Asian artists, Latino artists,” Kirwin says, and hopes that putting them online will encourage more research. The gift, she adds, will allow the Archives “to shine a floodlight on those collections.”

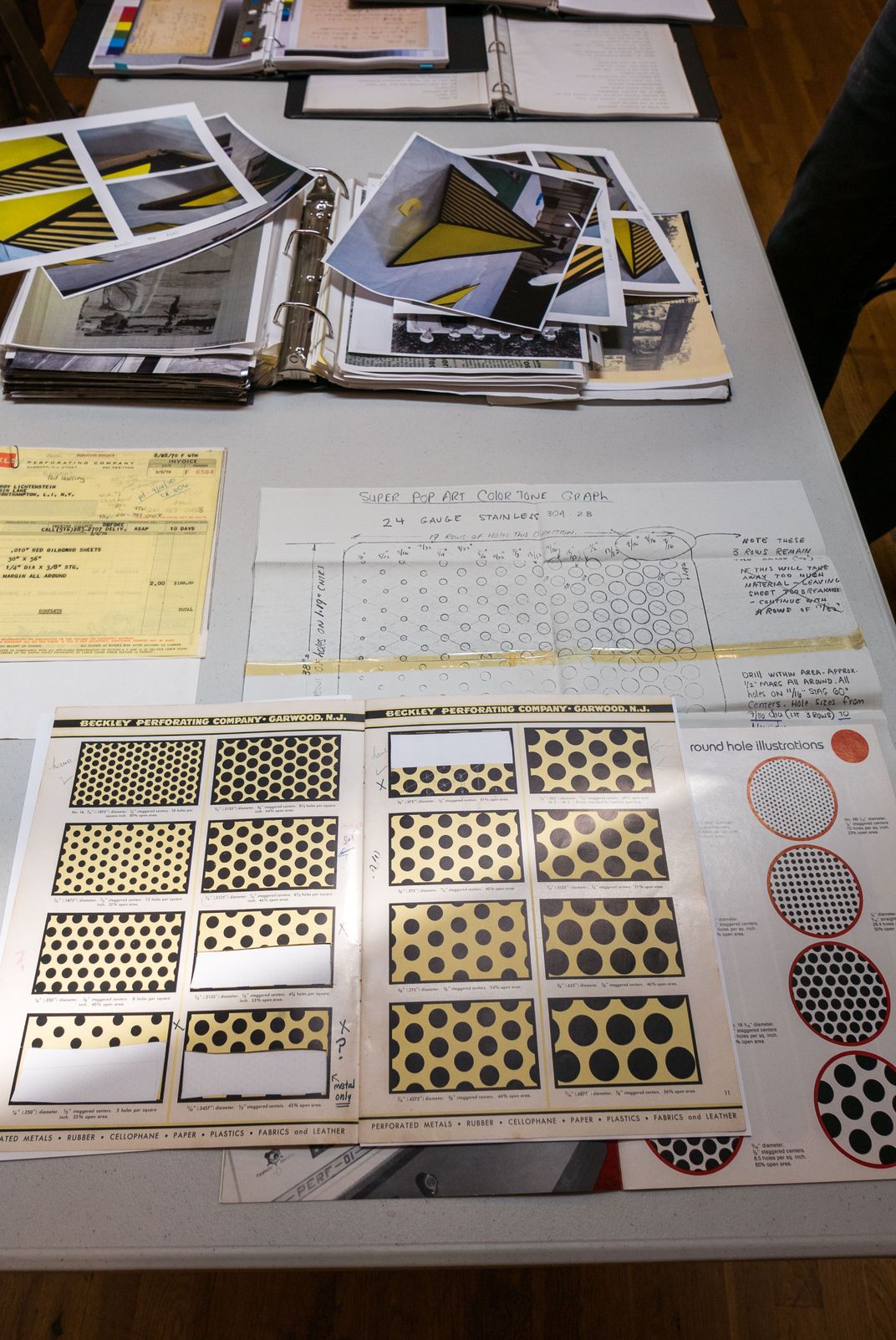

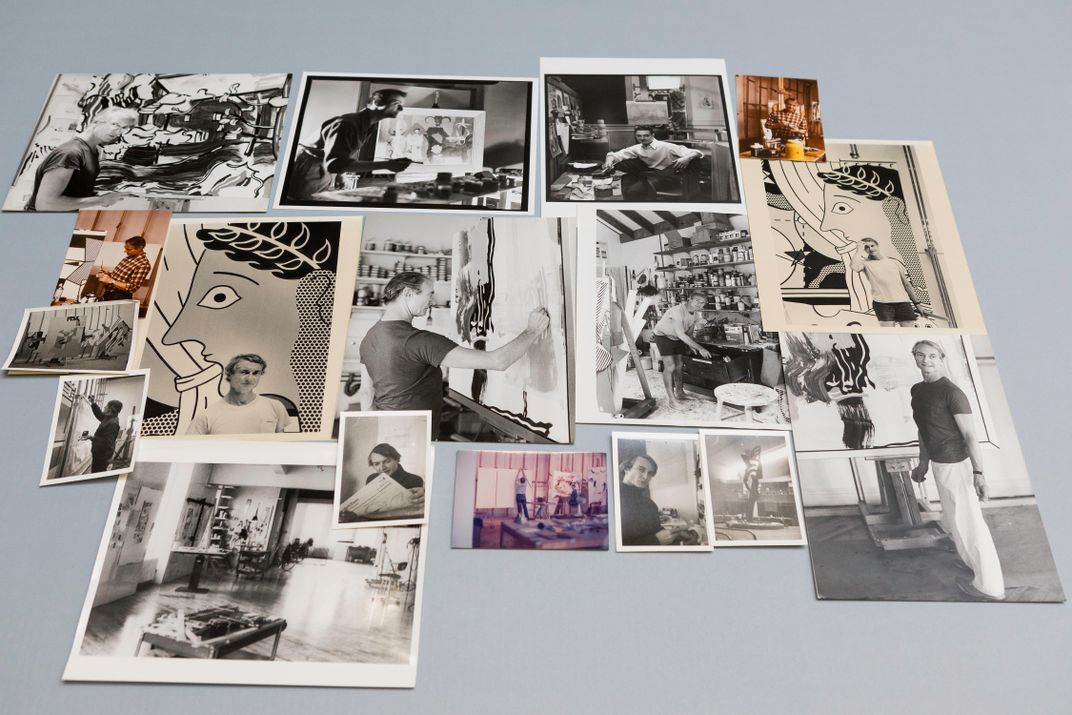

In November, Kirwin met with Brancato at the foundation’s offices in Greenwich Village, housed in Lichtenstein’s spacious former studio, where drops of paint can still be spotted on the floor. Spread over the tables around them were letters, notebooks, photographs by and of the artist, books, boxes of index cards, comic books, art supplies and more—a tiny fraction of the whole collection, which now covers more than 500 linear feet.

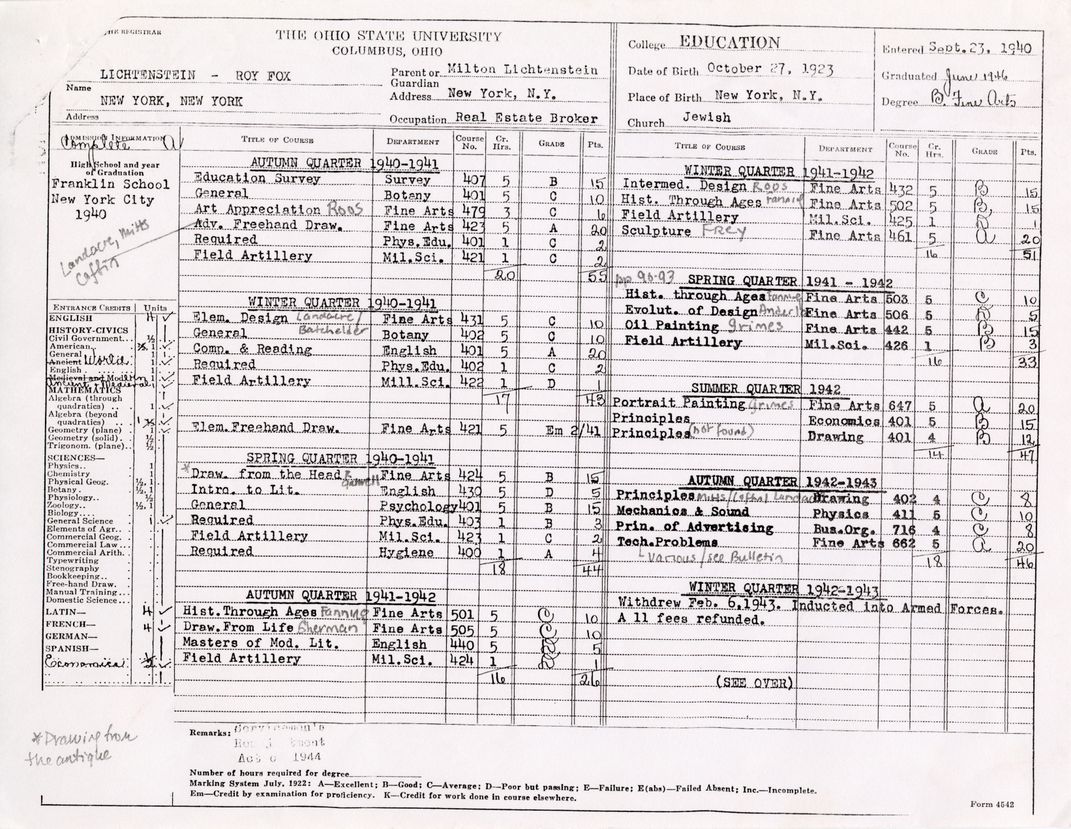

Brancato pointed out a copy of Lichtenstein’s undergraduate transcript from the early 1940s at Ohio State (he got an A in sculpture, a C in art appreciation and, in those wartime years, a D in field artillery). On a nearby table stood stacks of day planners from his years as a renowned artist in New York, detailing his meetings with artists, the poet Allen Ginsberg, Castelli and others, along with telephone logs noting who he spoke with, when and about what. Kirwin envisioned future scholars crunching all this data to reach a new understanding of, for example, the personal networks running through the art market.

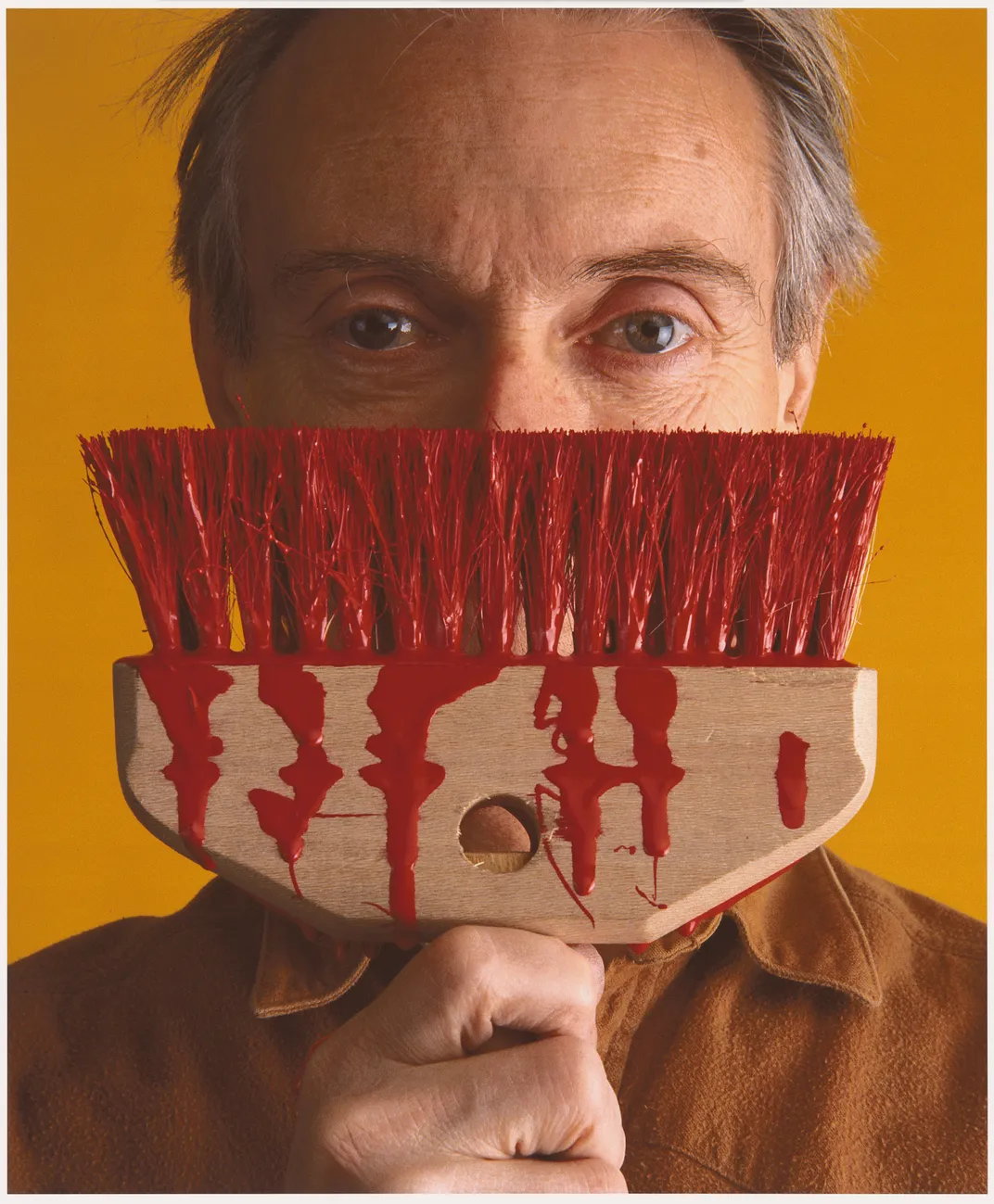

The foundation also holds binders and binders of source materials: clippings from the kinds of comics and newspaper ads that the artist recreated in some of his best-known works. Brancato noted a 1964 comic book next to a small image of Lichtenstein’s 1965 painting Brushstrokes. The painting is a four-foot-square canvas depicting three huge smears of red paint and, in the lower left corner, a hand holding a paint-soaked brush—all meticulously rendered in the artist’s signature comic-strip-style Ben-Day dots. Art historians have often seen it as a reply to the previous generation of artists, Brancato says, “a parody, almost, of Abstract Expressionism.”

Cut out of the old comic book is a single frame, which was nowhere to be found in Lichtenstein’s papers. So researchers hunted down another copy of the comic book, and then discovered that the missing frame depicted three familiar red brushstrokes, with the painter’s hand and brush in the lower left corner.

Did Lichtenstein base Brushstrokes on this frame because something in the comic book’s narrative spoke to him, and not solely as a comment on Abstract Expressionism? The comic book tells a creepy tale of an isolated, perfectionist artist who obsessively paints the same image over and over, until the face in his painting begins to talk, Brancato says, “telling him he is a pathetic, worthless artist.” Like the reclusive artist in the comic book, Lichtenstein was very shy. Though not a self-portrait, Brancato says, “it’s almost a reflection of the artist, that he’s so obsessed with himself, or the idea of perfection.”

As part of its research over the years, the foundation has also built an immense collection of interviews with people connected with Lichtenstein, but these oral histories haven’t been widely available. Even art historians who have worked with them, Brancato says, “don’t know we have over 250 or 300.” Soon the interview transcripts will go online alongside the Archives’ existing collection of more than 2,300 oral histories on American art.

Being able to search across all the oral histories will be a powerful tool for researchers, Kirwin says. “If you want to search the words ‘Ben-Day dot’ through the 250 [interviews], every instance, every context—if somebody mentioned that, and what they had to say about it—you will get there right away.”

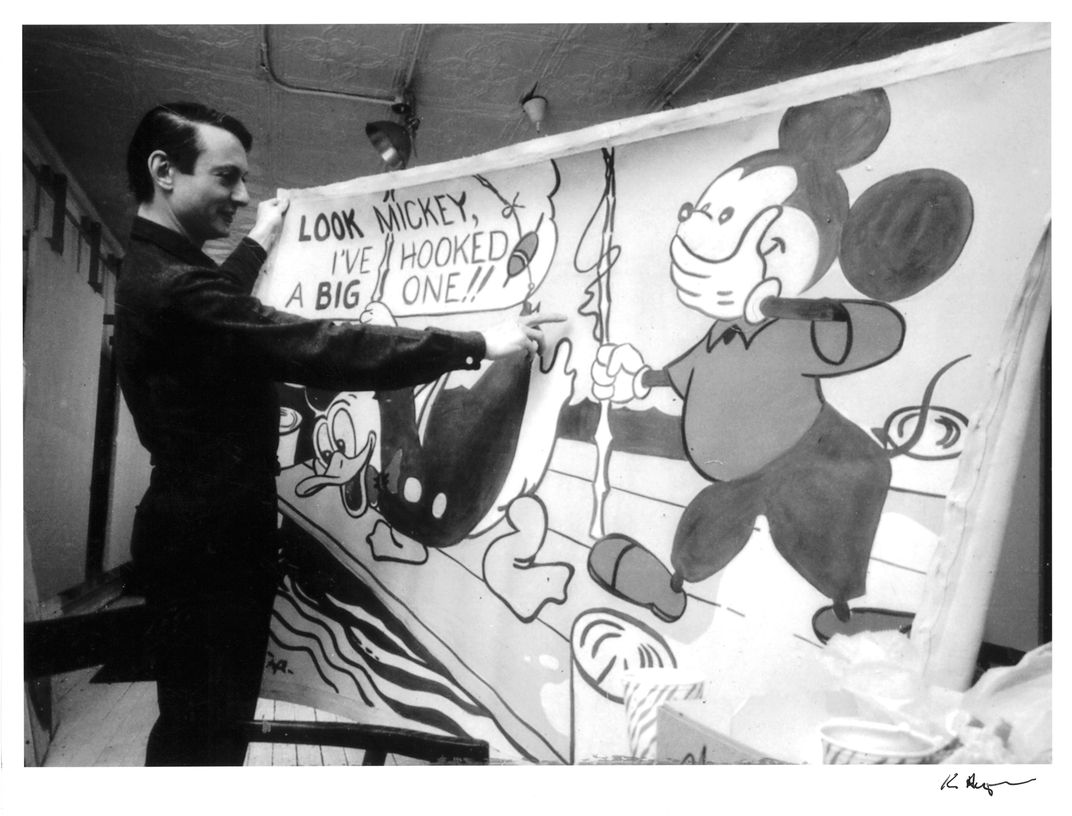

Not everything you read may be true, however. The 1961 painting Look Mickey, depicting Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck, signaled the arrival of Lichtenstein’s Pop style, and there has been much lore surrounding his inspiration for it. The foundation has a transcript of an interview with the late artist Allan Kaprow, who knew Lichtenstein at that time. In it, Kaprow recalled talking to Lichtenstein and praising a bold cartoon image on a bubble gum wrapper, saying, “and then at some point Roy smiled,” as if Kaprow had given him the idea.

“We think of this as highly fictional,” Brancato says, and in fact art historians have since located a different source image for Look Mickey, in a children’s book called Walt Disney’s Donald Duck: Lost and Found. The foundation has a copy of that book now, and anyone curious about Lichtenstein’s work can examine how he altered the original image to create his own painting.

Brancato and Kirwin paused to consider the archives’ transition from private collection to wide-open source. “Once the collection’s online, you won’t believe how many people will say, ‘Oh, I was in the living room when the photograph was taken,’” Kirwin says. “Things come out of the woodwork then, because it is so available. And that will also be a tremendous catalyst for finding new things and also new scholarship.”

There is risk, too, in letting go. Kirwin wonders about the “mythic stories:” will the fictional versions of history be replicated alongside, or in place of, the accurate ones?

“We worry about that a little bit,” Brancato replies. “One thing we’re able to do [now] is provide context, . . . show other kinds of documentation that maybe would . . . provide a deeper understanding.” Once the collection is set loose online, that ability to shape the story will be gone.

But, he adds, “This is a great opportunity for voices that we haven’t approved.” For two decades, the foundation has worked with curators and authors largely from “within our world,” he says. “Putting this all out there allows people who may be critical or have different ideas, that didn’t come to us directly—they have equal access to everything. So I’m very excited about that.”

“The thing about archives,” Kirwin says, “is that every generation takes a new look at things, so even if the material all stays the same, . . . the next generation of art historians will come along with a different question to ask of it. So it will continue to live and to produce.”

They wandered back to take another look at the letter denying Lichtenstein tenure. “We were thinking of doing an exhibition of rejection letters,” Kirwin says. “Just to give people faith.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SusannahGardiner.JPG)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SusannahGardiner.JPG)