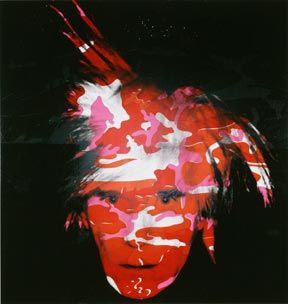

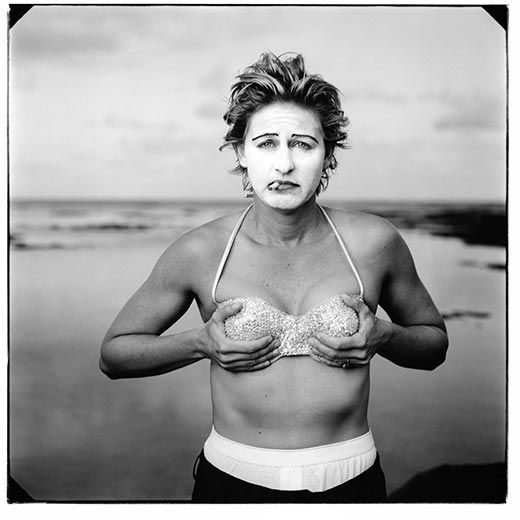

Portrait Gallery’s Hide/Seek Uncovers an Intricate Visual History of Gay Relationships

The show reveals how American artists as a whole have explored human sexuality

Get the latest on what's happening At the Smithsonian in your inbox.

Jesse Rhodes | READ MORE

Jesse Rhodes is a former Smithsonian magazine staffer. Jesse was a contributor to the Library of Congress World War II Companion.