The Powerful, Complicated Legacy of Betty Friedan’s ‘The Feminine Mystique’

The acclaimed reformer stoked the white, middle-class feminist movement and brought critical understanding to a “problem that had no name”

:focal(800x601:801x602)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ea/fd/eafd4a48-14b4-446b-98dc-7297cf2be92d/feminine-mystique.jpg)

Is it possible to address a “problem that has no name?” For Betty Friedan and the millions of American women who identified with her writing, addressing that problem would prove not only possible, but imperative.

In the acclaimed 1963 The Feminine Mystique, Friedan tapped into the dissatisfaction of American women. The landmark bestseller, translated into at least a dozen languages with more than three million copies sold in the author’s lifetime, rebukes the pervasive post-World War II belief that stipulated women would find the greatest fulfillment in the routine of domestic life, performing chores and taking care of children.

Her indelible first sentences would resonate with generations of women. “The problem lay buried, unspoken, for many years in the minds of American women. It was a strange stirring, a sense of dissatisfaction, a yearning that women suffered in the middle of the twentieth century in the United States.” Friedan’s powerful treatise appealed to women who were unhappy with their so-called idyllic life, addressing their discontent with the ingrained sexism in society that limited their opportunities.

Now a classic, Friedan's book is often credited with kicking off the “second wave” of feminism, which raised critical interest in issues such as workplace equality, birth control and abortion, and women’s education.

The late Friedan, who died in 2006, would have celebrated her 100th birthday this month. At the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, a tattered, well-read copy of The Feminine Mystique, gifted by former museum curator Patricia J. Mansfield, is secured in the nation’s collections of iconic artifacts. It was included in the museum’s exhibition titled "The Early Sixties: American Culture," which was co-curated by Mansfield and graphic arts collection curator Joan Boudreau and ran from April 25, 2014 to September 7, 2015.

“One of the things that makes The Feminine Mystique resonant is that it’s a very personal story,” says the museum’s Lisa Kathleen Graddy, a curator in the division of political and military history. “It’s not a dry work. It’s not a scholarly work. . . it’s a very personal series of observations and feelings.”

While The Feminine Mystique spoke bold truth to white, college-educated, middle-class women, keeping house and raising children and dealing with a lack of fulfillment, it didn’t recognize the circumstances of other women. Black and LGBTQ feminists in the movement were largely absent from the pages of The Feminine Mystique and in her later work as a leading activist, prominent members of the feminist movement would come to clash with her beliefs and her quick temper. She would be criticized for moderate views amid a changing environment.

Her contributions, however, remain consequential. She was a co-founder and the first president of the National Organization for Women (NOW), and helped create both the National Women's Political Caucus and the National Association for the Repeal of Abortion Laws, now known as NARAL Pro-Choice America. But her name is most tied to The Feminine Mystique, the book that pushed her and other discontented housewives into the American consciousness alongside the ongoing Civil Rights Movement.

Lisa Tetrault, an associate history professor at Carnegie Mellon University, emphasizes Friedan’s argument that women were being burdened by society’s notions of how they should live their lives. At the time, many women were privately experiencing, she says, “a feeling that the problem was theirs alone.”

“Part of what The Feminine Mystique did was shift this conversation from this individual analysis,” she says. Friedan’s book showed them a systemic analysis of how society was undermining women in order to keep them at home under the moniker “occupation: housewife.”

Historian and Smith College professor emeritus Daniel Horowitz, who authored the 1998 Betty Friedan and the Making of The Feminine Mystique: The American Left, the Cold War, and Modern Feminism also contextualizes the book at a time when other works were examining the restlessness of suburban life.

“She was, as a professional writer, acutely aware of these books and the impact they had,” he says. “It’s also a wonderfully written book with appeals on all sorts of levels. It’s an emotionally powerful book.”

Born Bettye Naomi Goldstein on February 4, 1921 in Peoria, Illinois, both of her parents were immigrants. Her Russian father Harry worked as a jeweler, and her Hungarian mother Miriam was a journalist who gave up the profession to start a family. She attended Smith College, a leading women’s institution, as a psychology student, where she began seeing social issues with a more radical perspective. She graduated in 1942 and began postgraduate work at the University of California, Berkeley. Friedan would end up abandoning her pursuit of a doctorate after being pressured by her boyfriend, and also left him before moving to New York’s Greenwich Village in Manhattan.

From there she began work in labor journalism. She served as an editor at The Federated Press news service, and then joined the UE News team, the publication of the United Electric, Radio and Machine Workers of America. Her activism for working class women in labor unions, which included African Americans and Puerto Ricans, is crucial, says Horowitz, toward understanding the formation of her feminism.

However, he adds that her public embrace of labor unions during the feminist movement did not occur until the later years of her life, and that The Feminine Mystique omits her early radicalism. “Her feminism in the 50s and 60s is very self-consciously based on the civil rights movement,” he says. “She thinks of NOW as an NAACP for American women.”

Betty married Carl Friedan in 1947, and the couple had three children. The family moved from Queens to New York’s Rockland County suburbs in 1956, and she took on the job of housewife while freelancing for women’s magazines to add to the family income.

It was at a Smith reunion where Friedan found inspiration for what would become The Feminine Mystique. Intending to survey her classmates who had worried that a college education would get in the way of raising a family, what she instead found was a lack of fulfillment among the housewives. Other college-educated women she interviewed shared those sentiments, and she found herself questioning her own life role in the process.

To create The Feminine Mystique, Friedan included both the experiences of women she talked with and her own perspectives. She set about to deconstruct myths on women’s happiness and their role in society. “Gradually, without seeing it clearly for quite a while,” Friedan wrote in the book’s preface, “I came to realize that something is very wrong with the way American women are trying to live their lives today.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/64/cc/64ccdc28-99d1-41fd-b2a9-7024ec39d898/npg_2000_7-friedan.jpg)

Even before it was created the book was contentious: the president of the publishing house referred to its premise as “overstated” and “provocative.” And while it caught flak from some reviewers—a New York Times review rejected its premise and stated that individuals, not culture, were to blame for their own dissatisfaction—it was a major hit for female readers.

“It was quite fantastic the effect it had,” Friedan later said in an interview with PBS, “It was like I put into words what a lot of women had been feeling and thinking, that they were freaks and they were the only ones.”

Following the success of her book, Friedan moved back to New York City with her family, and in 1966 helped establish NOW with colleagues. She and her husband divorced in 1969, just a year before she helped lead the Women’s Strike for Equality that brought thousands of supporters to the city’s Fifth Avenue.

She pushed the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission to end sex discrimination in workplace advertising, advocated for equal pay, and pressured changes to abortion laws, among others. Friedan also supported the Equal Rights Amendment, which failed to meet state ratification in 1982 but has since garnered renewed interest.

By the end of Friedan’s life, the movement had moved much farther than she had been able to keep up with. She had already been criticized by some feminists for a lack of attention to issues afflicting non-white, poor and lesbian women, and had made disparaging remarks toward the latter. When conservatives made cultural gains in the 1980s, she blamed radical members for causing it, denouncing them as anti-men and anti-family.

“One of the things that should come out of the women’s movement,” she told the Los Angeles Times, “is a sense of liberating and enriching ways of working out career and family life, and diverse ways of rearing our children and figuring out how to have a home and haven.”

Friedan had decidedly become a moderate voice among feminists, but nevertheless kept active. She served as a visiting professor at universities such as New York University and the University of Southern California, and in 2000 wrote her memoir Life So Far. In 2006 she passed away in Washington, D.C. on her 85th birthday.

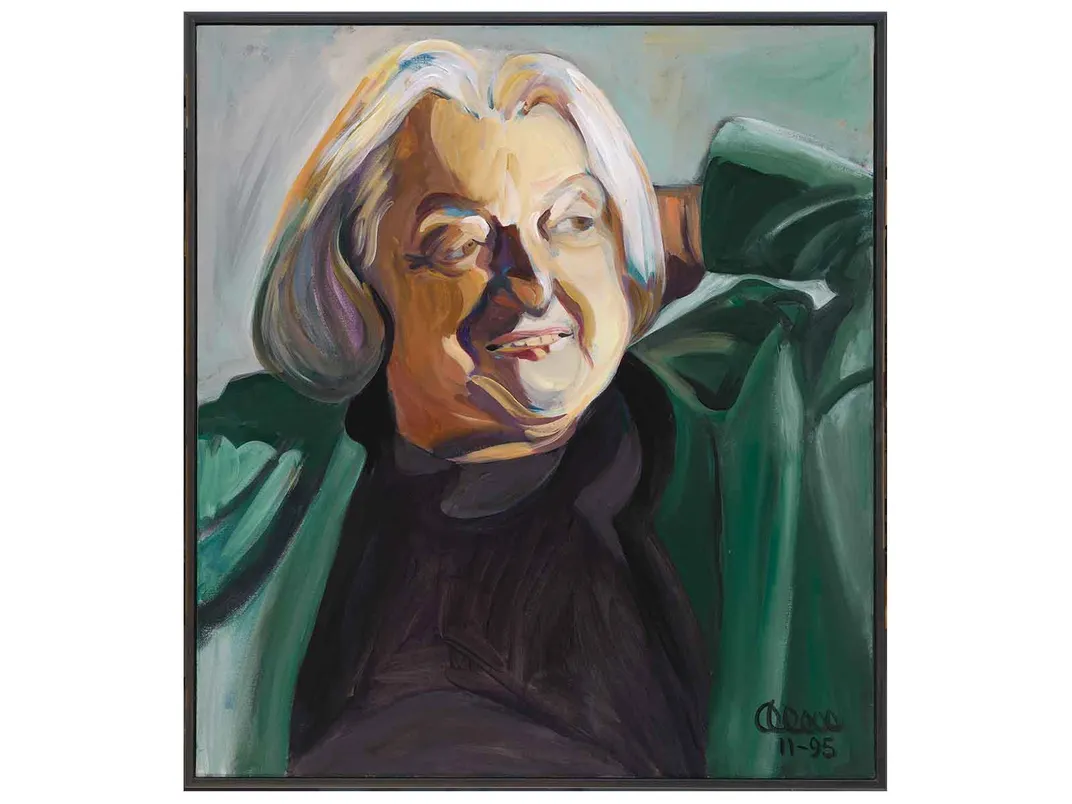

Two canvas paintings depicting Betty Friedan are held by the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery. One in acrylic, created in 1995 by Alice Matzkin, shows the reformer looking to the side with her hand behind her head in a contemplative pose. The other, painted with oil in 1999, was donated by the artist Byron Dobell in 2000 and features Friedan focused on the viewer with a vague sense of interest.

Looking back on Friedan’s seminal book, The Feminine Mystique, its narrow scope is important to recognize. As Graddy notes, it focuses on the aspirations of certain white college-educated housewives, rather than women who were not white nor middle class, among others.

“[T]hese are women who also have the leisure time to organize,” Graddy says, “They have the leisure time to become the women who start to organize different facets of feminism, who can organize now, who have connections that they can make and time that they can expend.”

Kelly Elaine Navies, a museum specialist in oral history at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, discusses the disconnect between The Feminine Mystique and black women of the time.

“It did not directly impact the African American community, as a large percentage of African American women worked outside of the home by necessity,” she writes in an email. “In fact, the prolific African American writer and activist, Pauli Murray, who was a co-founder of NOW, along with Freidan, did not even mention The Feminine Mystique in her memoir.”

The claim that The Feminine Mystique brought forward the “second wave” of feminism is also dubious. Not only is the characterization of waves misleading, as the calls made during different movements can overlap while individual waves feature competing beliefs, but as Graddy notes, the activism doesn’t simply fade when it receives less attention. She also mentions that describing the book as the beginning of the women’s movement only makes sense when applied to a certain group of feminists.

Tetrault says that The Feminine Mystique not only fails to discuss how the cultural expectations of the idealized housewife also afflicted non-white and poor women who could not hope to achieve that standard, but it also doesn’t provide meaningful structural solutions that would help women.

“In some ways Betty Friedan’s solution of just leaving home and going and finding meaningful work,” she says, “left all those structural problems that ungirded the labor that women provide through domesticity unaddressed, and that’s a huge problem.”

Even with the book’s flaws, it remains an important piece of history while having shaped the women’s movement. While Horowitz contends that a feminist movement still would have occurred without its publication, he says it nevertheless impacted the lives of hundreds of thousands of women.

And as Navies points out, the material it didn’t include caused black feminists to spread ideas that were more inclusive of American women in society, as they even formed their own term “womanist” to distinguish from the more exclusive “feminist.”

“In retrospect, as a catalyst for the second wave of feminism,” Navies writes, “The Feminist Mystique was a factor in the evolution of black feminism, in that black feminists were compelled to respond to the analysis it lacked and develop a theory and praxis of their own which confronted issues of race, class and gender.”

Tetrault adds that The Feminine Mystique’s message that societal constructs were harming women resonated throughout the whole of feminism.

“That would be a kind of realization, that would ripple through the movement on all kinds of different fronts. . . that the problem wasn't them,” she says. “The problem was the set of cultural expectations and cultural structures around them.”