The Story of a Ballet Wardrobe Mistress

The precise stitchwork of May Asaka Ishimoto, a second generation Japanese American who survived two years in an internment camp

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f6/e1/f6e19b6f-8033-478d-864e-42f564523929/momballetcropped.jpg)

Sometimes through the passing of a great American, we discover a story that is very much alive, and preserved with the artifacts they leave behind.

So when we heard about the death of May Asaki Ishimoto, a second generation Japanese American who survived two years in a World War II internment camp to become one of the country’s most established ballet wardrobe mistresses, we went looking for a surviving relic through which we could tell her story.

We found it in the collection of the National Museum of American History, in the form of a tutu made for prima ballerina Marianna Tcherkassky in the production of Giselle; a gentle, flowing costume whose precise stitch work gave the fabric enough structure to endure countless hours and performances.

But before we could tell that story, we had to go back to where the story of the “backstage pioneer of American Ballet” began: in the 1960s suburbs of Washington, D.C., where Ishimoto began making costumes for her daughter Mary’s dance classes.

Mary Ishimoto Morris, now a writer who lives in Laurel, Maryland, was five or six years old at the time, and can remember the first costumes her mother made clearly: beautiful pink and sparkly clown outfits.

“She would just be bent over her sewing machine late into the night making those costumes," Mary said. "It was pretty exciting for me at the time, all the shining material, and the sequins and the buttons.”

For Ishimoto, making ballet costumes wasn’t a far leap from the other artistic things she could do well, said her daughter Janet, of Silver Spring, Maryland. It seemed a natural progression from her other projects, including Japanese painting, which she used to decorate several full sets of china dinnerware still used by the family; weaving; knitting sweaters; sewing slip covers and curtains; and making clothes for her children and husband.

But those were all just hobbies—Ishimoto never thought making dance costumes for her daughter’s class would turn into a nearly 30-year career with some of the most prestigious ballet companies in the country.

“She told me when she looked back on it, it looked as if she had it all planned out,” Mary said. “But at the time, she said none of this had ever occurred to her. She didn’t have any big dreams of working with the biggest stars in ballet, but it just kind of happened.”

Ishimoto impressed the teachers at her daughter Mary’s studio, and when one of those teachers joined the National Ballet of Washington, D.C. in 1962, he discovered their costume maker couldn’t sew. They called Ishimoto and that “temporary position” turned into a full time job where she found herself making hundreds of costumes for several productions.

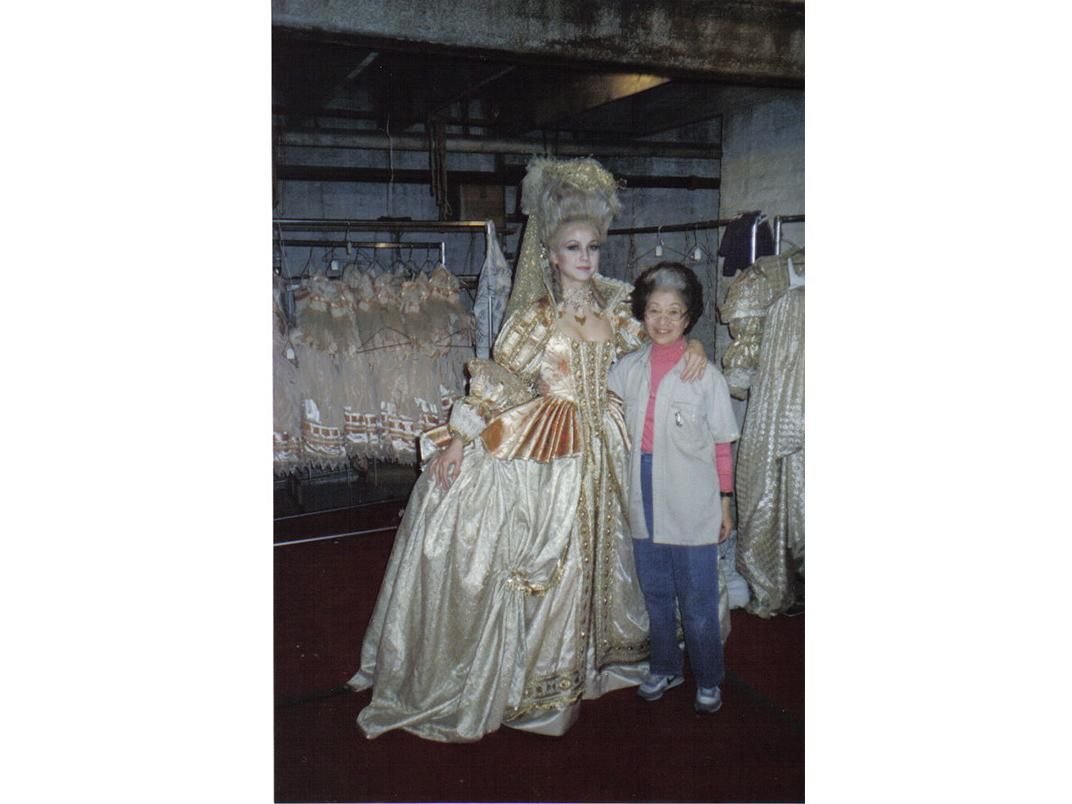

Soon her workshop moved from the family home to a dim room underneath the theater’s stage, where tutus hung in careful rows and costumes still in progress lay wherever there was space. The best part for both of her daughters, they said, was going to see the performances, and afterwards, meeting the dancers.

“It was just magical," Mary said. "Ballet was magical to me, and to know that our mother was part of creating that made us really proud.”

In 1970, Ishimoto retired, or so she thought. But her reputation had caught the attention of several other companies, including the New York City Ballet. There, she agreed to a “temporary assignment” that lasted two years, from 1971 to 1973. After that, she moved on to the American Ballet Theatre, also in New York City, where she worked from 1974 until she retired (this time for good) in 1990. Her work in both Washington and New York quickly fostered lasting friendships with several famous dancers, including Tcherkassky, one of the first and most famous Asian Pacific American prima ballerinas; Dame Margot Fonteyn; and Mikhail Baryshnikov.

In a note Baryshnikov sent the family after Ishimoto’s death, he wrote, “her quiet spirit and dedication to the theater were reminders to every ABT dancer that beauty is found in the smallest details . . .a bit of torn lace, a loose hook and eye, a soiled jacket—these were her opportunities to pour energy into an art form she loved, and we were the richer for it.”

The costume in the Smithsonian’s collection was donated after Franklin Odo, the director of the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American (APA) Program, contacted the family and worked with them to find a garment made by their mother that the museum could preserve. They found it with Tcherkassky, who was happy to donate the tutu she wore in the title role of Giselle—Ishimoto’s favorite ballet.

“She was always very self effacing and very humble but she was very flattered and very proud to have the costume there,” Janet said.

Some of Ishimoto’s creative talent also was passed down to her children. Janet says she “inherited” her mother’s love for trying new projects, making her own clothes and slipcovers, sewing curtains and taking watercolor and sketching classes. And Mary, the young ballerina who beamed at her mother’s talent with costumes, became a writer—which, as it turns out, has proven helpful in preserving more of her mother’s stories.

In 1990, the same year she put down her sewing needle, Ishimoto picked up her pen and with Mary's help, began work on her biography, finishing the manuscript just this past year and compiled a list of her acknowledgments just days before she died. Though they have yet to find an agent, Mary said the family is confident her book will find a publisher.

“To our knowledge a memoir by a ballet wardrobe mistress hasn't been published yet, and. . . her behind-the-scenes recollections will be of interest to the artists she documented as well as to their families and fans,” Mary wrote in an e-mail.

It will also, like the tutu, help keep her story alive.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erica-hendry-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erica-hendry-240.jpg)