A Previously Unknown Portrait of a Young Harriet Tubman Goes on View

“I was stunned,” says director Lonnie Bunch; historic Emily Howland photo album contains dozens of other abolitionists and leaders who took an active role

:focal(1413x698:1414x699)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8d/b4/8db48331-198d-406e-b91c-5a793537a9ef/2017_30_47_001detail.jpg)

The power exuded by a previously unknown portrait of Harriet Tubman is tangible. The escaped slave, who repeatedly returned to the South risking her life to bring hundreds of enslaved people North to freedom, stares defiantly into the camera. Her eyes are clear, piercing and focused. Her tightly waved hair is pulled back neatly from her face. But it is her expression—full of her strength, power and suffering—that stops viewers in their tracks.

“Suddenly, there was a picture of Harriet Tubman as a young woman, and as soon as I saw it I was stunned,” says a grinning Lonnie Bunch, founding director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. He’s talking about a portrait of Tubman contained in an 1860s-era photography album belonging to abolitionist Emily Howland.

“All of us had only seen images of her at the end of her life. She seemed frail. She seemed bent over, and it was hard to reconcile the images of Moses (one of Tubman’s nicknames) leading people to freedom,” Bunch explains. “But then when you see this picture of her, probably in her early 40s, taken about 1868 or 1869 . . . there’s a stylishness about her. And you would have never had me say to somebody ‘Harriet Tubman is stylish.’”

But Bunch, a historian with expertise in the 19th century, then looked a little deeper at the portrait of this woman Americans think they know so well. Not only did she escape slavery and conduct hundreds of others to freedom along the Underground Railroad, she served as a spy, a nurse and a cook for Union Forces during the Civil War. She also helped free more than 700 African-Americans during an 1863 raid in South Carolina, which earned her another nickname: General Tubman. Bunch says the photograph celebrates all of those facets of Tubman’s life.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bb/ca/bbca0fdc-3bc7-4ac0-8194-969b86f35766/55671u.jpg)

“There’s a youthful exuberance. There is a sense that you could actually look at that picture and say, ‘Now I understand that this woman was tough and resilient.’ A picture like that does a couple of things. First,” Bunch says,” it reminds people that someone like Harriet Tubman was an ordinary person who did extraordinary things. So, this means you too can change the world. . . . But I also think one of the real challenges of history is that sometimes we forget to humanize the people we talk about . . . and I think that picture humanizes her in a way that I would have never imagined.”

In the photograph, Tubman is wearing a pleated, buttoned blouse with ruffles at her forearms and wrists, and a flowing skirt. Bunch says it is clearly the attire of a middle-class black woman, and she could well afford the clothing.

“She had a pension from working for the Union government, being a spy, that sort of thing. But more importantly she had a little farm,” Bunch explains, “so she was able to sell eggs. . . . But there was also support coming in from abolitionists. They would send her money, they would celebrate her. . . . I think the most important thing is that she had to find a way to make a living, and she did.”

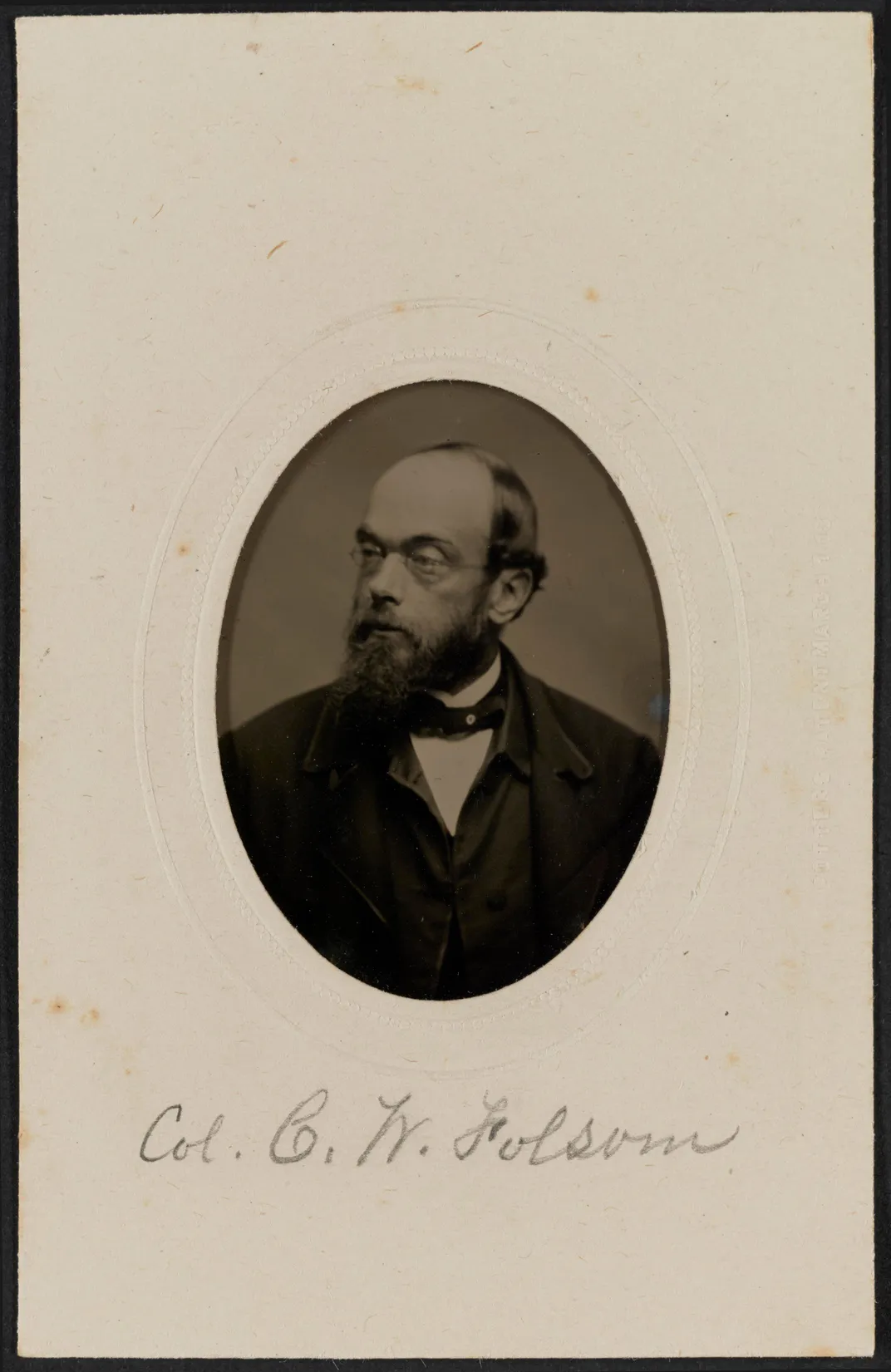

Howland’s photo album containing the portrait of Tubman was unveiled this week in the museum’s Heritage Hall. Bunch and Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden jointly lifted the draping off of the display case in the main entry area—with the album opened to the previously unknown Tubman portrait. The two institutions jointly acquired it from the Swann Auction Galleries of New York. But as Hayden notes, the 49 images in the album include photos of many involved in education, abolition and freedom, including Sen. Charles Sumner, abolitionist Lydia Maria Child and Col. Charles William Folsom. There are also pictures of some of Howland’s African-American students, who later became teachers, and former Washington D.C. Mayor and abolitionist Sayles Bowen.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5e/32/5e3220f8-df4f-4e67-af62-5c9704d16a37/2017_30_47_001.jpg)

“Harriet Tubman was a change maker and a trailblazer—a citizen who helped shape this country. This amazing album gives us a new view of her life, along with dozens of other abolitionists, educators, veterans and leaders who took an active role in citizenship,” Hayden says.

Museum curator Rhea Combs says the photo album was a gift to Emily Howland from her friend, Carrie Nichols, on New Year’s Day in 1864. Both were teaching at the Camp Todd school on Robert E. Lee’s Arlington Estate.

“Emily Howland was an incredible woman who was a Quaker, was deeply religious and was also involved as an abolitionist and in the women’s suffrage movement. She was even involved at Camp Todd during the Civil War,” Combs explains. “But she ended up moving to upstate New York and starting a school for freed persons of color and she just had a rich, dynamic history in terms of her commitment to social justice, women’s rights and to the education of African-Americans.”

Howland lived in Auburn, New York, where Tubman was living at the time the previously known picture of her was taken. The two women were friends and lived close to one another. The museum’s historians imagine a circle of abolitionists coming together after the Civil War, intending to use the rest of their lives to continue fighting for fairness.

“Most of the people in this album are dynamic, committed, political figures, educators, individuals who have been really instrumental in improving the conditions for the American public,” Combs explains, “so this album really speaks to these larger questions around liberty, around justice for all. And it just makes the most sense that (Howland) would have Harriet Tubman as the capstone image right at the end of the album to really encapsulate all of the things that this album embodies.”

Combs says the placement of the album in the museum’s main entry hall puts it front and center for those coming in, and sends them a message.

“I want them to see promise and potential and I want them to see what the museum’s ethos is really about,” she explains. “You’re seeing the American story through the African-American lens. You literally get a chance to look at a young, determined Harriet Tubman, and understand that she is part of this kind of lexicon of a community of dedicated individuals both black and white, male and female, who have helped to ensure that America lives up to the promise and tenants upon which it was built.”

There’s one other image in the Howland album that floored the museum’s historians. It contains the only known photograph of John Willis Menard, the first African-American man elected to the U.S. Congress. He is impeccably coiffed, with curls at the ends of his mustache.

“When we came across the picture of John Menard I was stunned, because John was the first black elected to Congress after the passage of the 15th amendment. He was from Illinois but had moved to Louisiana and was elected to Congress,” director Bunch says. “But his opponent challenges the election, and so there was this debate about whether or not he should be seated in the House. There is this amazing image of him speaking before the House of Representatives. . . . But they decided that neither he nor his opponent should be in the House, so they basically kept the seat vacant. So, while he was the first elected he didn’t actually become a member of the House of Representatives.”

This photograph, Bunch says, is almost as exciting as the image of Tubman. But he thinks the Howland album helps teach people that one of the great moments in America was the abolition of slavery, and it was pushed and initiated by both enslaved and free African-Americans. He says it is a moment where you see America at its best.

“You see people crossing racial lines, you see people risking it all to say ‘This is an abomination. A country that is built on liberty should not have slavery,’” Bunch says. “So for me, it is one of those moments that remind us that when America is at its best what it can do, and that this kind of interracial alliance is crucially important.”

Bunch says he also loves the fact that people will see images of African-Americans who believe in an America that didn’t believe in them, who said that they were going to demand that America live up to its stated ideals.

“That just inspires me to fight all the fights we have today,” Bunch says.

The Howland photo album will be on display in the museum’s Heritage Hall through March 31, 2019; and will then go on permanent view in the “Slavery and Freedom” exhibition in the museum’s History Gallery.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7a/bf/7abf4a6b-54ae-4c01-9b86-0a82a91ca39b/2017_30_8_001.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/35/30/3530aa27-6242-44e0-85f8-15897f979c72/2017_30_1_001.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f6/10/f610fb3d-f999-4638-b8bc-8e3a8edd01ec/2017_30_21_001.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c9/73/c9730b61-918e-461c-9067-d7a3e815f22d/2017_30_35_001.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/91/43/91432645-9a4d-4e14-aa4f-14460e2a6722/2017_30_48_001.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)