Probing the Paradoxes of Native Americans in Pop Culture

A new exhibition picks apart the cultural mythologies surrounding the first “Americans”

:focal(3827x1894:3828x1895)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/77/66/77669bae-ba37-4b10-b531-ce9084e655fe/americans3.jpg)

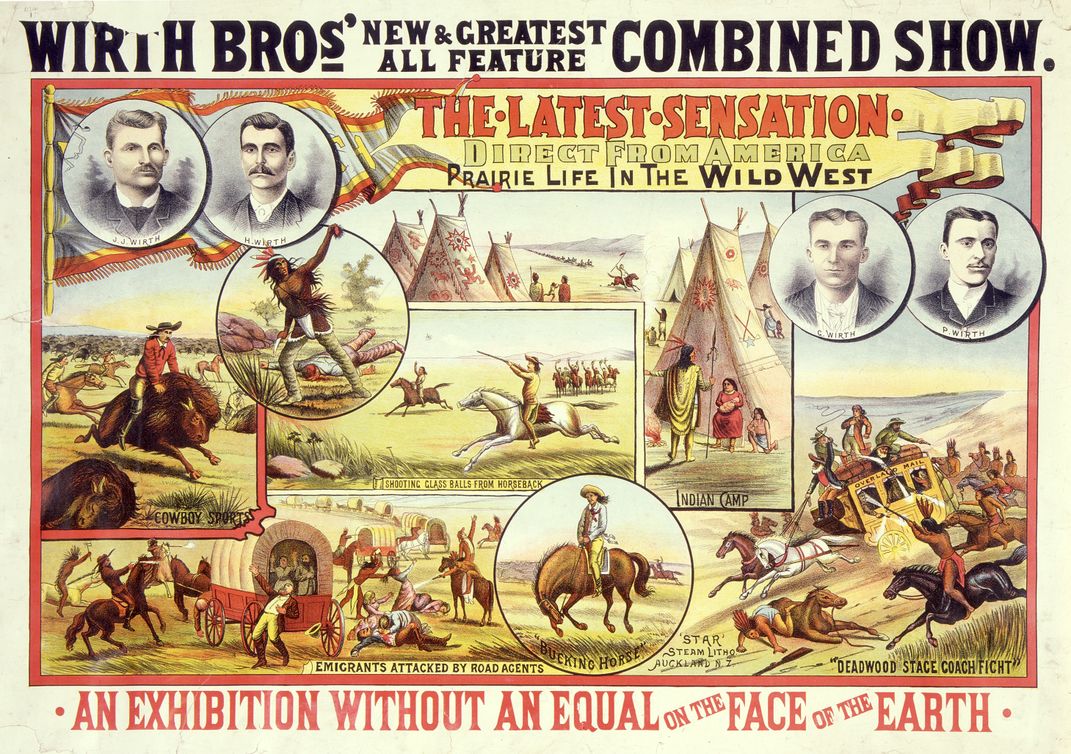

Festooned with a colorful collection of movie posters, magazine spreads, supermarket products, college merchandise and more, the towering walls of the 3,000-square-foot gallery space at the heart of the National Museum of the American Indian’s new “Americans” exhibition are initially downright overwhelming.

Here, a sporty yellow Indian-make motorbike; there, a bullet box from the Savage Arms gun company. Here, an ad for Columbia Pictures’ The Great Sioux Massacre; there, scale models of the U.S. military’s Chinook, Kiowa and Apache Longbow helicopters. It’s a dizzying blizzard of pop cultural artifacts with nothing at all in common—save for their reliance on Native American imagery.

“The only unifying thing,” says curator Paul Chaat Smith (Comanche), “is that American Indians somehow add meaning or value to a product.” He says that the cultural love affair with native peoples on display in the “Indians Are Everywhere” portion of “Americans” is nothing new. “It never goes out of fashion,” he says. “It always makes sense to name a product after Indians.”

Smith believes that, while seemingly mundane when taken individually, the objects in the “Indians Are Everywhere” gallery regarded as a collection speak volumes to America’s ongoing obsession with Indians and Indian stereotypes. “This is a unique phenomenon,” he says. “It’s a completely extraordinary thing.”

Portrayed as uncivilized and unsophisticated in certain contexts, Native Americans are painted as principled warriors in others, and as sage dispensers of wisdom in others besides. America's outlook on Indian life is by turns lionizing and loathing, honorific and ostracizing. “Indians Are Everywhere” invites viewers to contemplate a complex tapestry of iconic imaginings of Indians, and to ask themselves why exactly Native Americans have for so long enthralled our nation.

“They’re a part of people’s lives,” Smith says, though usually “it’s normalized so you don’t really see it.” The exhibition “Americans” sets out to change that. “We’re letting people see it.”

In addition to revealing to museumgoers the uncanny ubiquity of Indian images in our society, “Americans” calls into question the accuracy of those representations. Branching off of the main gallery are rooms devoted to three famous but frequently misconstrued historical events: the Battle of the Little Bighorn, the Trail of Tears, and the life of Pocahontas. The exhibition corrects the record on each of these topics, providing guests with much-needed context.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/74/19/74197e8b-9b45-4bbf-8554-4309c55b9758/americans1.jpg)

It’s true that Little Bighorn, known to Native peoples as the Battle of the Greasy Grass, was a catastrophe for General Custer’s 7th Cavalry Regiment. But what’s important to remember is that it was a single blip of Native American victory in a ruthless American military campaign, one which soon after resulted in the confinement of Sioux Indians to reservations and the annexation of their land for U.S. development. Mythologized in the popular consciousness as a great triumph of the Native American warrior over white settlers, Little Bighorn was in reality the last gasp of an overpowered and dispossessed Indian alliance.

The Trail of Tears, “Americans” reveals, is also a severely oversimplified bit of history. Rejecting the popular conception of an isolated event spearheaded by Andrew Jackson, the exhibition shows that the Indian Removal Act passed in 1830 during Jackson’s tenure began a systematic campaign of forced displacement, one that impacted 67,000 Indians from numerous tribes across the terms of nine separate presidents at a cost of $100 million. Writing all of it off as the odious policy of a single man is too easy—this was a program that enjoyed wide support, and that was aggressively implemented by many elected officials, and for generations.

Pocahontas, popularized by Disney’s wildly inaccurate 1995 animated movie, was not a princess overcome by romance so much as a captive specimen for tobacco pioneer John Rolfe to parade around England as a testament to the wonders of the New World. Though she was instrumental in restoring the faith of English investors in the American colonial experiment, Pocahontas lived a tragic life, and died just prior to her return trip from Britain to Virginia at approximately 21 years of age.

These case studies were chosen for their familiarity—though few Americans are acquainted with the true details of each example, most will enter the exhibition with vague preconceptions of the terms “Little Bighorn,” “Trail of Tears” and “Pocahontas.” This is a show intended to “meet visitors where they are,” says Smith. “A lot of people don’t necessarily know a lot about this history, but we knew everyone’s heard of these things.”

By dispelling these enduring American myths and providing in abundance mass-market depictions of Native American lives, “Americans” forces us to come to terms with the fact that the liberal appropriation of Indian culture is as American as Uncle Sam, and exposes the surprisingly small amount we really know about Native Americans despite our continued attraction to fantastical portrayals of them. Everyone is apt to find something from their own lives to connect to in “Americans”; the show illustrates that we are all, in our own ways, complicit in this uniquely American phenomenon.

“If we’ve succeeded, visitors will find a new way of seeing,” Smith says. “Not just a new way of seeing the imaginary Indians that have surrounded them since birth, and not just a new way to understand Pocahontas and Little Bighorn and the Trail of Tears and how they transformed the entire country. They will see their own lives as part of a larger national story, and that all of us inherit the profound contradictions at the heart of the American national project.”

“Americans” will be on view at the National Museum of the American Indian through 2022.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)