When Pulling a Lever Tallied the Vote

An innovative 1890s gear-and-lever voting machine mechanized the counting of the ballots so they could be tallied in minutes, not hours or days

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ac/7a/ac7a49cc-b373-4664-b0c1-4b68205a950f/voting-machine.jpg)

Like most Americans, I still remember my first vote in a presidential election. I think I won't mention the candidates, though rest assured Warren G. Harding was not one of them. Much time and many votes have passed since then, but the memory remains vivid for several reasons. The vote meant that I had reached the age—21 in those bygone days—when I could legally claim my place in the world of adults. It meant, too, that I was not just reading in textbooks about democracy but was actually taking part in its most sacred ritual. That first vote was high on the list of growing-up thrills, right up there with getting my driver's license and having my first legal drink (a manhattan in Manhattan).

What made the moment particularly memorable, too, was the booth into which I stepped to exercise my right and responsibility. Here's how it went: once inside, I moved a large lever to close a curtain. The action of that lever unlocked a bank of smaller levers, one next to each candidate. After pushing those levers to cast my votes, I returned the large lever back to its original position, the curtain opened, and I stepped out and smiled at my fellow voters waiting their turns—briefly a public figure proud of my private act of citizenship.

Throughout much of this country's post-Revolutionary history, writers and politicians have invoked the ballot as a symbol of a right fundamental to our democracy. Now, as the nation moves to vote once more, it seems appropriate to pay homage to another powerful symbol of our right to make our voices heard. Occupying pride of place among the artifacts in the current exhibition at the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History "American Democracy: A Great Leap of Faith" is an 1890s prototype of the classic gear-and-lever booths in which I and many Americans cast their votes.

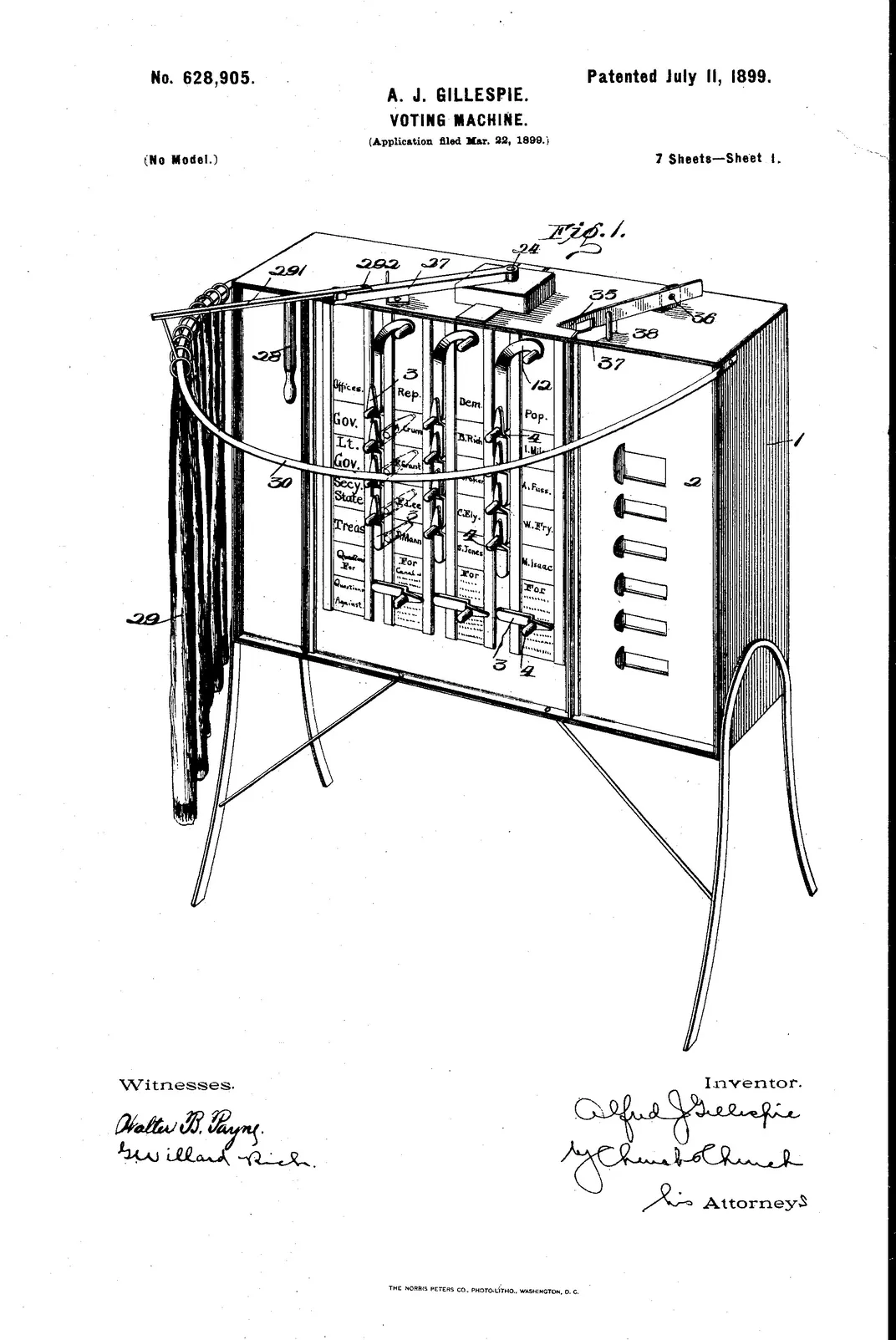

As far back as the mid-19th century, political reformers sought to make voting more systematic (and, they hoped, more honest). In the late 1890s, New York inventor Alfred J. Gillespie devised a gear-and-lever machine (derived from earlier patents by Jacob H. Meyers) that offered privacy while limiting one man to one vote. (Women were denied the vote until 1920.) The advantages of Gillespie's machine over the ballot box were many, including that it kept a running count, thus speeding up the reporting of results. The machines also could be locked by officials when voting was over, preventing—or at least reducing—tampering. This extraordinary new device wowed the voters in an 1898 town election in Rochester, New York. As the Brooklyn Eagle reported: "Where other cities were hours and even days in counting their votes, Rochester knew the complete result in the city on every office—State, County, Assembly, Senate and Congressional—in just thirty-seven minutes. There was not a mistake, not a hitch."

Gillespie's glorious gizmo, which cost $550 in 1898—equivalent to $11,600 today—was manufactured well into the 1960s, even as other systems proliferated, notably the punch-card method that introduced the term "hanging chad" into the national vocabulary.

But the booths were not embraced universally. Lawsuits filed in various states over the years claim that voting by lever does not constitute the "vote by ballot" guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution. Most jurists have held that the machines are indeed a form of paper ballot and that the secrecy the paper ballot was intended to ensure is not compromised by lever technology.

Curator Larry Bird, one of the curators of the exhibition, says the gear-and-lever machine, came to the Smithsonian in the early 1960s, a gift of the Rockwell Manufacturing Company in Jamestown, New York.

"The old gear-and-lever machines are built like bank vaults," Bird points out, "and weigh about as much." The expense of moving, storing and maintaining them made the machines increasingly unpopular with budget-squeezing officials. When the very portable Votomatic device—a lightweight machine, its ballot keyed to a punch card—became available, the curtained booth's days were numbered. Manufacturers stopped making spare parts in the mid-1980s.

Though it's hard to argue with bottom-line reality, loss always accompanies gain. "There's a physicality to the lever-action booth," says Bird. "When you cast your vote that way, you really feel you've done something."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)