Q+A: How To Save the Arts in Times of War

From Iraq to Libya, Corine Wegener works to preserve priceless objects of human history

![]()

Sites like Iran’s Persepolis are on world heritage lists, but that won’t spare them from harm during armed conflict. Organizations like the Committee of the Blue Shield help protect such sites. Photo by Elnaz Sarbar, courtesy of Wikimedia

After serving in the Army Reserve for 21 years, and working at the Minneapolis Institute of the Arts as a curator, Corine Wegener now travels the country training soldiers in cultural heritage preservation. As the founder of the U.S. Committee of the Blue Shield, Wegener covers everything from material science to museum organization to international law and often calls on Smithsonian curators and collections to help impress upon the soldiers the importance of the shared cultural items she calls touchstones. A unit preparing to deploy to the Horn of Africa, for example, received a special tour at the African Art Museum.

Now at the Smithsonian as a cultural heritage preservation specialist, Wegener’s played a critical role in the recovery of the National Museum of Iraq after devastating looting took place there during the war in 2003.

An estimated 15,000 items were stolen and the collection was in disarray. Former director general of Iraqi museums, Donny George Youkhanna, says ”Every single item that was lost is a great loss for humanity.” He told Smithsonian magazine, ”It is the only museum in the world where you can trace the earliest development of human culture—technology, agriculture, art, language and writing—in just one place.”

Many, though not all of the objects, have since been recovered and the museum reopened in 2009. But Wegener says recent experiences in Libya, Syria and now Mali show how much work there is left to do.

The 1954 Hague Convention helped create international guidelines for handling cultural property during armed conflict but it took the Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives of WWII, who helped save some of Europe’s most iconic artifacts, as a model. How did that team from Civil Affairs manage to do that?

The very first line of defense for collections and monuments and historic places is the people that work there every day. Those are the people who are going to do an emergency plan, do a risk assessment, figure out what will we do if this collection is at risk, or if there is a disaster.

During World War II, a lot of collections were hidden away. They were moved to underground storage locations and this was all throughout Europe. In Italy for instance, they built a brick wall around the statue of David. They completed de-installed the Louvre. . .It was protected, first of all, by the cultural heritage professionals who cared for those things every day and a lot of people risked their lives to hide these things from the Nazis, especially the sort of “degenerate” art that were trying to destroy. When they decided, just prior to the invasion of Italy, that they would institute these Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives teams in the middle of the war, some of the other allied countries did this as well. They made maps to try and let the allied bombers know where some of these important places were.

They would try to avoid them, but of course, they didn’t have nearly as sophisticated targeting systems as we do today. And they also had the teams that would go out and advise the commanders and say, this is an important cathedral in the center of town, let’s try to avoid it. But often times it just wasn’t possible, there was still this doctrine of military necessity that if something had to go it had to go.

But Eisenhower put out this famous letter to his commanders on the eve of the invasion of Italy basically saying, yes, there may be military necessity but when you come across cultural heritage, you better be sure it’s a military necessity and not just laziness or personal convenience on your part. If you decide it needs to be destroyed, you’re going to answer to me.

A posting used by Monuments officers in Northern Europe in Italy during World War II to mark cultural sites. National Records and Archives Administration

A crew transports the Winged Victory of Samothrace from the Louvre Museum in Paris. Monuments Men Foundation

Lt. Gen. Omar N. Bradley, Lt. Gen. George S. Patton and Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower inspect German collections stored in the Merkers mine. National Records and Archives Administration

What does Blue Shield do?

The Hague Convention is a really good plan but how do you execute it in reality? It says, avoid these cultural sites. Well, you can figure out a few because they’re on the World Heritage List but what about a contemporary museum building full of ancient collections, that’s not going to be on a World Heritage List? We don’t have a list like that, why do we expect these other countries to be able to provide that at a moment’s notice too?

It’s a goal that I think each country needs to work toward, but in the meantime, it feels a little bit like we’re scrambling when something happens like the Libya no-fly zone. We really had to scramble to put together something because otherwise they would have had very little information about what to avoid during that bombing. I think after that, the awareness is out there and there’s a lot more people out there working toward that goal now, which I think is really great.

Iraqi Col. Ali Sabah, commander of the Basra Emergency Battalion, displays ancient artifacts Iraqi Security Forces discovered Dec. 16, 2008, during two raids in northern Basra. Photo by United States Army

When you are in those scrambling situations, are the governments helping you?

No, and especially in a case like Syria or Libya, no, because the government is who they’re fighting against. What we try to do is, we go through the whole Blue Shield network. For instance, part of the Blue Shield international network is the International Council of Museums. They have contacts in their membership within these countries. They try to reach out to people. If they don’t work for the government, that might work. If they work for the Ministry of Culture, they may hesitate to cooperate with such a request because what if they are found out and get fired or get shot, it’s a big risk.

Our next level of queries are to our colleagues in the United States who excavate in those countries and they have a lot of information, often times GIS coordinates for archaeological sites in those countries and often they will also know at least some site information for museums, especially if they have archaeological contents. That’s why Smithsonian is such a great resource because you have so many people doing research in these various countries and have experience and contacts there where they can reach out in a more unofficial way to get information. People are often very willing to provide this information if they know that their identity is going to be protected and that it’s kind of as an aside to a friend. It’s a trusted network and we only provide the information on a need-to-know basis.

The Timbuktu manuscripts are some of the objects at risk during the current conflict in Mali. Photoy by EurAstro: Mission to Mali, courtesy of Wikimedia

What is the situation in Mali right now?

The big issue there right now is the intentional destruction of the Sufi tombs which the Islamic extremists see as against Islam because they’re seen as venerating a sort of god in the form of this Sufi mystic. They don’t think people should be making pilgrimages to these tombs. The Islamic manuscripts are really important also but so far I have not heard of any instances where they’re being destroyed and my understanding is that they’ve been kind of spirited away to various locations and that’s a good thing. That’s exactly what happened in Baghdad too, some of the more important Islamic manuscripts were hidden away in various mosques and homes and that’s what kept them from the looters.

What is the toughest part of the job?

One of the toughest things in a situation like that is to work with the owners of the collection, be it a private non-profit foundation or a gallery or a country like a ministry of culture, to get them to think about prioritizing the damaged collections and to quickly commit to what they want to do first. It’s like asking people to choose their favorite child.

People ask the question, how can you worry about culture when there are all these people dead or homeless and suffering? What I learned in my travels in going to Baghdad and Haiti and other places is that that’s not for you to decide. That’s for the people who are effected to decide. Without a doubt, every place I have been, it’s been a priority for them…I was thinking about this the other day when somebody asked me this question for the millionth time and I thought, it’s always an American who asks that question. I have never been asked that by somebody on the ground when I’m working.

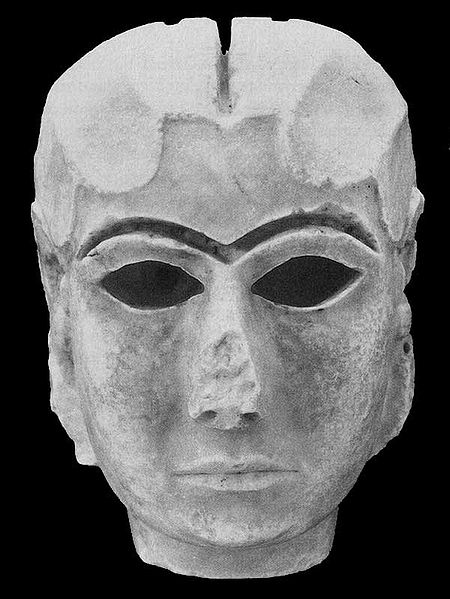

More than 4,000 years old, the Warka Mask, also known as the Lady of Warka and the Sumerian Mona Lisa, was one of the objects stolen from the National Museum of Iraq. Courtesy of Wikimedia

Do you have a personal triumph, an object you’re personally proud of that you can point to and say I helped save that and we’re better for it?

I don’t know how much personal credit I can take for it, but my favorite save is getting back the head of Warka in Iraq. The military police unit that was working in the area recovered it in a raid. They were looking for illegal weapons and objects that had been looted from the museum. They caught one guy who had a couple of museum objects and he said, if you let me go, I’ll tell you who has the most famous object in the Iraqi national collection, the head of Warka. They found it and called me up. They brought it to the museum the next day and we had a huge press conference to celebrate the return. People call it the Mona Lisa of Mesopotamia and seeing that come back was one of the highlights of my life. The museum just completely had an about-face. Everybody became motivated again to get things back in order, it was great.

Update: Though it was initially believed, according to reports from the Guardian, that many of the manuscripts housed in Timbuktu may have been burned by extremist militants, later reports from the New York Times indicated that the manuscripts had instead been successfully hidden.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)