Q+A: The Youngest of the Little Rock Nine Talks About Her First Day of School

Carlotta Walls LaNier recently donated the dress she wore on what would’ve been her first day at the desegregated high school

![]()

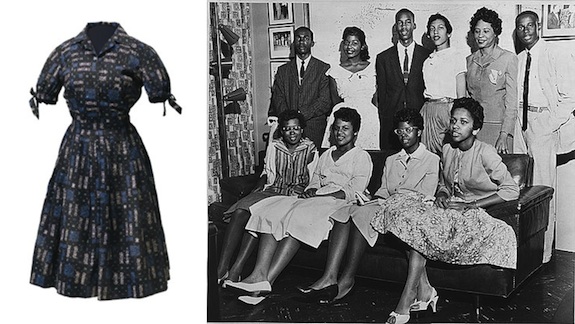

One of the nine students who desegregated Little Rock, Carlotta Walls LaNier (top row, third from right) recently donated her dress (left) from what would have been her first day of school. The group is pictured in 1957 with civil rights activist Daisy Bates, who helped lead the effort to integrate Little Rock. Photo by Cecil Layne, courtesy of the Library of Congress

Carlotta Walls set out for her first day of 10th grade in a new dress. The year was 1957, and the school was Little Rock Central High. Walls and eight other African-American students were stopped by a white mob opposed to desegregation, and the ensuing confrontation between Arkansas and federal authorities took 20 days and Army troops to quell.

Walls recently donated the dress—patterned with numbers and letters—to the National Museum of African American History and Culture. Bill Pretzer, a curator, says her great-uncle bought it thinking, “Desegregating Little Rock merits a store-bought dress.” Walls graduated from Little Rock Central in 1960, after her home was bombed that February.

“I really did want that diploma,” she says, “to validate all of the crap that I had gone through.” Carlotta Walls LaNier, now 70, is president of the Little Rock Nine Foundation, which works for equal access to education.

National Guardsman prevents the students (including Carlotta Walls on the left) from entering the school, September 4, 1957. Photo by Will Counts, courtesy of Arkansas History Commission

For your first day of school at Little Rock Central High School, why was that store-bought dress so special?

“We didn’t purchase too often, to be honest with you, if you understand the Jim Crow South, you couldn’t try on clothes, and so forth, as I grew up. My mother was an expert seamstress, so she just made all of our clothes, including hers. My great uncle, knew that that was the case and he wanted me to have a store-bought dress to go to my new school, so he stopped by the house and asked my mother, he said, here’s the money and I want you to go get her a store-bought dress.”

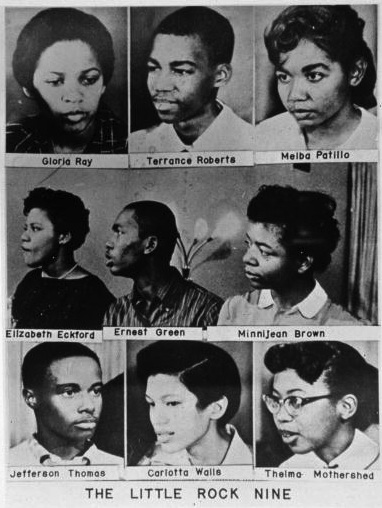

Of the nine students, pictured here in their 1957 yearbook photographs, Carlotta Walls was the youngest.

What were you thinking life at your new school would be like?

“I knew that we could not do any extracurricular activity…I knew I was giving that piece up but I just figured that the following year I’d be able to get back to extracurricular activities. That part was okay. It was excitement for me, to be going to a new high school, and to be the one that was in my neighborhood. So that was what was going on in my mind.”

“Yes, I saw all of the anger, and the ugly faces across the street, but I ignored them, and I really did consider them ignorant people. To be honest with you, that is what really got me through the whole year, that I knew this was ignorance that was making these statements and not the type of people that I would associate with.”

The evening newspaper’s front page after the students were denied entrance to the school.

Were your parents worried to send you?

“I think they were more proud of the fact that I had signed up to go without a discussion with them.”

“I know they were nervous by what they were reading, but they also felt confident that we were doing the right thing. When I wrote my book, I read some quotes of my father’s and he felt that, he had served in World War II, I had a right to go to that school and his tax dollars helped pay for that school, for the schooling that went on. And he felt that they didn’t separate his taxes, so why should we be separated as far as going to school?”

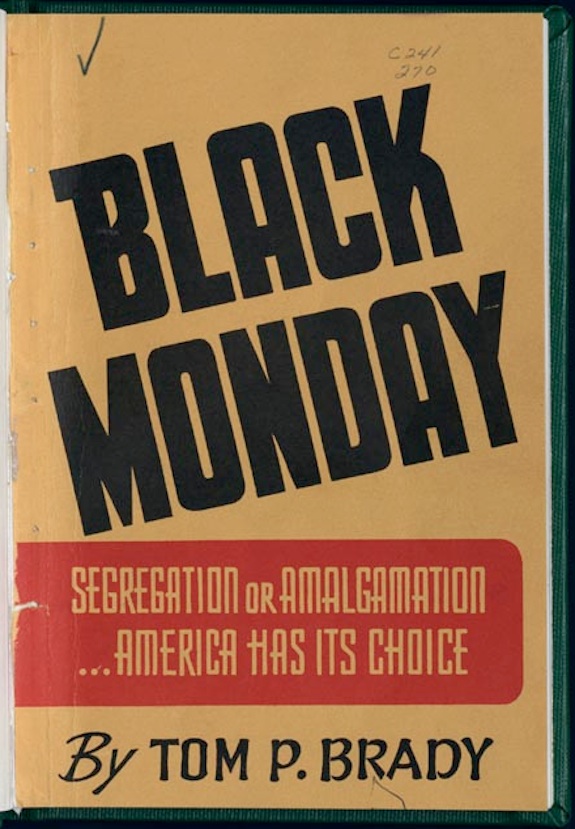

“Black Monday” was coined to mark the date of the Brown v. Board of Education decision, Monday, May 17, 1954. In protest, the White Citizens’ Council movement in Mississippi, led by Thomas Pickens Brady, a circuit court judge, published this handbook, Black Monday, calling for the nullification of the NAACP, the creation of a 49th state for African Americans, and the abolition of public schools. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

As the youngest, how did you relate to the rest of the Little Rock Nine?

“I listened to the seniors and juniors, even when I was in junior high school, I looked up to those who were older and were doing well, they were role models for me.”

“I must admit as the months went on, I recognized we were all equal in this, so you know my decision making got sharper and more focused, I think I was focused to start with, otherwise I wouldn’t have gone there anyway, but as far as decision making I was making some decisions that were somewhat different than some of the others because I looked at the landscape a little bit differently.”

“One in particular. . .I was thinking about Minnijean and Melba and a couple of others who bought their lunch every day in the cafeteria. That was a battleground in my mind that, you knew that you were going to have to deal with being pushed and shoved. . .in line to purchase your lunch. So I brought my lunch every day, so I wouldn’t have to deal with that. I dealt with it enough in the hallways and in the classrooms. My one break was having lunch, so why have to continue that sort of thing in the lunch line?”

Protestors, one with a Confederate flag, gather at the capitol building to protest the reopening of the public schools in 1959. Photo by John Bledsoe, courtesy of the Library of Congress

“Race Mixing Is Communism,” read one protestor’s sign. 1959. Photo by John Bledsoe, courtesy of the Library of Congress

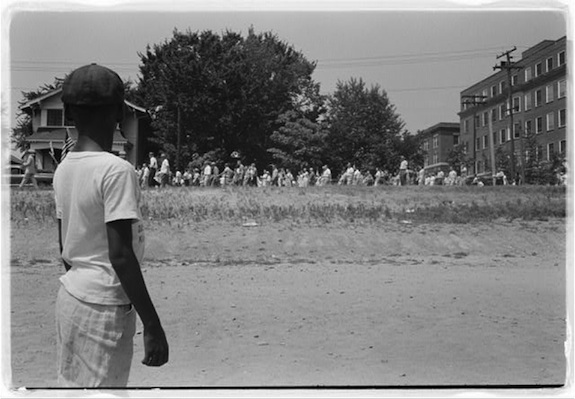

A young kid watches the mob of protestors as they march from the capitol building to the high school. 1959. Photo by John Bledsoe, courtesy of the Library of Congress

But you made it through the first year and then came back your senior year, even after the governor closed the school for an entire year?

“I was determined to finish that year, I was not going to give up, because that way they would’ve won, and I was not about to let that happen. Because of my sports involvement, I was a pretty competitive person. I was just not going to let that happen. I didn’t have to go back, but after awhile, after that first and the second year the schools were closed, I went back my senior year to finish, because I really did want that diploma to validate all of the crap that I had gone through.”

“I remember being back on the campus and the fact that there were no guards there to protect us. I was cautious, there was no question about that, however, I also felt that the senior class members were in the 10th grade with me. . .they had suffered just like I had in a sense with school being out and they were low people on the totem pole too, so now that they were in a leadership position, they were determined not to have the same sort of things to go on. Not to say that they stopped a lot of things, but the tone was different and they didn’t want the schools to be closed either, they were happy to be back in school.”

New York Mayor Robert Wagner greets the Little Rock Nine students, shaking hands with Carlotta Walls on his right and Thelma Mothershed on his left, in 1958. Photo by Walter Albertin, courtesy of the Library of Congress

Why did your mom keep your first day of school dress all those years?

“She just packed it up and put it in the cedar chest. I think not knowing, but at the same feeling that it meant something, she kept it. And I’m just happy she did.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)