In This Quiet Space for Contemplation, a Fountain Rains Down Calming Waters

One year after the Nation’s first black president rang in the opening of the African American History Museum, visitors reflect on its impact

Visitors to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture are often overwhelmed by its heart-wrenching exhibitions. The museum explores everything from the horrors of segregation to triumphs in music, the arts and the ongoing battle for civil rights. It can be a lot to take—especially the “Slavery and Freedom” exhibition that begins in the bowels of the museum, three stories below ground.

“I was really angry with what I saw downstairs,” says Shelley Lee Hing. She’s from Jamaica, but now lives in Arlington, Virginia, and was on her second visit. “I know about it. But when you see it, it comes back to the forefront of your thoughts. “

But Lee Hing says visitors shouldn’t want to deny the things that they see here.

“You want people to understand the struggles that African Americans went through, and the fact that this country was built on their backs literally,” Lee Hing says.

Both she and her sister, Nadine Carey, were focused on the positive as the museum celebrates its first birthday. On September 24, 2016, massive crowds filled the National Mall as President Barack Obama, the nation’s first black president, officially dedicated the new museum with the ringing of a bell to signal the official opening, after nearly a century of fitful planning.

“This is a good way to remember, and to kind of keep your eyes on the prize,” Carey explains. “You have to think of the future of our kids. You know what you don’t want them to go through, so this is a way to educate them. This is how we were. We don’t want them to turn back the clock. We want to keep going forward.”

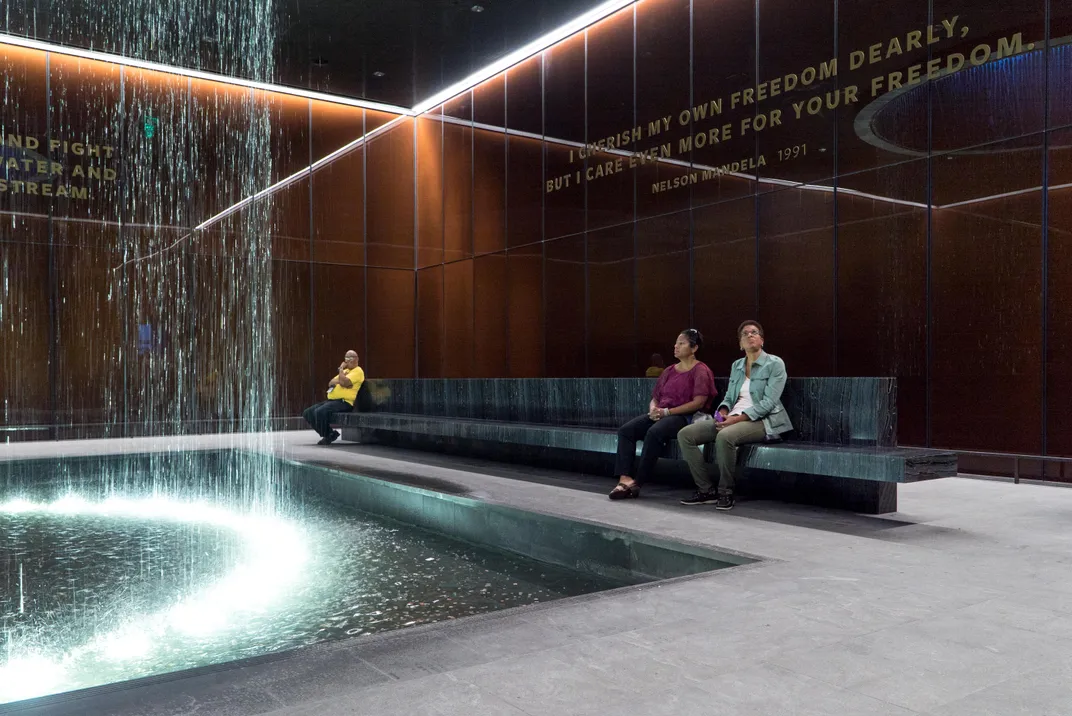

The two were standing in a very special place within the museum, called the Contemplative Court. It’s a gorgeous room, with caramel-bronze walls of Bendheim glass. They have a core of luminous mesh, striking a balance somewhere between opacity and translucency, and look as if a subtle light shines within them. Lee Hing and Carey call it a great place to decompress.

A cylindrical fountain rains into a pool in the center of the room, coming from a skylight above. The water creates a sound that conveys something in the midst between a feeling of white noise, and calming relaxation. Some visitors come here and sing. Others sit quietly, staring into the constantly shifting liquid pool. It is a space for deep thoughts and meditation.

“The scene down there—is pretty strong stuff. Slavery, and then it goes up and you can see the difference in the years and the changes that happen,” says Anna Pijffers, visiting from the Netherlands. “I think also when you’ve seen the whole museum; you can come here, and think about what you saw. This is a good thing.”

She finds the room to be both quiet and noisy, because of what she calls the waterfalls, but she is impressed and inspired by the quotes that adorn walls that look like they could warm you like a fire.

“I cherish my own freedom dearly, but I care even more for your freedom,” reads a 1991 quote from former South African president and anti-apartheid revolutionary Nelson Mandela.

On another wall: “We are determined. . . to work and fight until justice rains down like water and righteousness like a mighty stream,” from Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., circa 1958.

From African American abolitionist, poet and suffragist Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, who died in 1911: “I ask no monument, proud and high to arrest the gaze of the passers-by; all that my yearning spirit craves is bury me not in a land of slaves.”

Finally, and simply, from Sam Cooke’s iconic song: “A change is gonna come.”

“This place was specifically designed after a lot of conversation, and understanding that we were taking people on a very important journey,” explains Esther Washington, the museum's director of education. “Most of our visitors, by the time they come to the Contemplative Court, will have visited the history gallery and that is a very emotional place.”

Washington says if one has been through all of the history exhibitions, including segregation, people have walked more than a mile. They’ve also journeyed through difficult subjects and stories, and then through the tumultuous changes that have and continue to shake the foundations of our nation. She adds that the Contemplative Court shares some characteristics with similar spaces at other museums dealing with equally emotional content, such as the National September 11 Memorial & Museum in New York City, and the United States Holocaust Museum in Washington, DC.

“There is a room at the Holocaust Museum, and it is near the end of the experience where you can go in and light a candle in memory, and I have seen this type of room in other spaces,” Washington says. “I think (ours) is very unique because there is power in moving water. Water is referenced in other parts of our building. The Middle Passage, in psychology it’s the reference of cleansing oneself, of purification.”

Perkins +Will’s Phil Freelon served as lead architect for the design collaboration, known as Freelon Adjaye Bond/Smith Group JJR. He says water as a cleansing, spiritual element has been used in architectural features for millennia. But this room, he says, is totally different.

“It’s cylindrical, there’s a roof over it . . . there’s water coming from above. You could say that about a lot of different places around the world,” Freelon says, “but how we do it and how it fits in the storyline and ambiance of the space is what’s unique and what is powerful for the museum.”

He says the driver behind the thought process of the creation of the Contemplative Court, is that the majority of the building is below ground. Once you know the beginning of the story is below street level, Freelon says it was clear that bringing some light down in certain places would be a good thing to do.

“But if you have exhibits that have technology associated with them and in special lighting, you don’t necessarily want or need a lot of natural light,” Freelon says. “On the other hand, you know if you’re going through some difficult stories and artifacts, reading and seeing part of the African American story, and you know this engenders some strong emotion, we felt it would be appropriate to have a place in the museum where folks could come and experience natural light.

Freelon says the room is both a refresher, and respite from looking at so much material.

“We wanted punctuation marks in the story and between exhibits where people can regroup . . . discuss, contemplate what they’ve seen, and then move on,” Freelon explains, adding that from the very beginning of the design ideas it was clear that water would be part of the space. There’s also a water feature on the south side of the museum’s exterior, he says, that picks up the spirituality and cleansing element for both the outside and inside. The museum is able to reclaim some of the rainwater and runoff in the outside feature. In the Contemplative Court, the water comes from the city system and is treated in a way so that there are no contaminants in the water vapor in the enclosed space.

Freelon says there was a lot of thinking about the cylindrical shape of the fountain that falls gracefully from the skylight, like a shimmering glass curtain.

“We call it the Oculus, because light is coming down,” Freelon says. “The root word goes back to Latin . . . your ocular nerve, so that’s an easy verbal reference to the eye. That’s a round part of the body, and it just made sense to bring light down in that cylindrical, circular form.”

It is also a counterpoint to the very regular geometry of the building’s rather square, layered crown shaped exterior that is often ablaze with reflected sunlight.

“We felt that something circular at that point . . . made sense because you can flow around, and you can sit around, not on any hard edges. It just seemed like the right form as opposed to something rectangular,” Freelon says.

The museum’s Washington says the Contemplative Court is a good place for the museum’s visitors. Fifty percent are over the age of 50, and the majority of visitors are between 60 and 90 years old. In museums, she notes, people are always looking for a place where they can just sit down for a little while with their families. But the room is a place of joy as well as a place for reflection.

“We’ve had two proposals in this space . . . and people have come in their bridal regalia to try and use the space for that moment, but we’re not allowed to have ceremonies here so that got shut down,” Washington laughs, because such things aren’t allowed in a federal building. “People have posted proposals online. So it’s just kind of a fun moment when we hear it’s happening from the floor and we all come down to just watch because it’s kind of amazing what people feel the space is.”

But for visitors like Anna Pijffers, looking up at the cascading fountain, the space is also a symbol of hope for how she and some others think the world could be.

“I’m thinking you see the rain falling, and rain falling can mean tears of slavery, and of the time that was,” Pijffers says, but “time goes on. The world goes on. Everything is change. . . . There’s no difference between the black and white. It’s one community.”

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture will celebrate the first anniversary of its opening September 23 to 24 with performances, public programs and extended hours.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)