The Rank and File Women of the Black Panther Party and Their Powerful Influence

A portrait taken at a “Free Huey” rally defines the female force that both supported and propelled the movement

:focal(1666x533:1667x534)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/65/0e/650ef0c5-c647-49b1-91fa-f15cae6978cc/2012_83_6_001.jpg)

It’s a striking photograph: six young black women with a spectrum of complexions, faces paused in mid-exclamation, fists raised in simultaneous solidarity at a Black Panther rally. Even their afros are emphatic and resolute as they stand in tandem in Oakland’s DeFremery Park, then and now a popular gathering place for the community’s African-Americans. There, a grove of trees honors Bobby Hutton who, at just 16, had been the Panthers’ first enlisted member and at 17, died after police shot him—purportedly, as he tried to surrender.

On this day, supporters assembled to demand the immediate release of Huey Newton, co-founder of the party and its national minister of defense, who was being held for assault, kidnapping and first-degree murder charges in the October 1967 death of police officer John Frey. Newton’s fate was to be decided at the superior court in overwhelmingly white Alameda County, where it seemed unlikely that a black revolutionary could get a fair trial. Of the 152 potential jurors who were interviewed, only 21 were black. All but one was systematically excluded from the selection process.

Husband-and-wife photojournalists Pirkle Jones and Ruth-Marion Baruch captured the image of the women on stage in August 1968. What isn’t visible is the utopian 72 degree-day or the thousands of members, neighbors and onlookers who peopled Defremery Park’s sun-beamed lawns to hear the Panthers’ message. When former party member Ericka Huggins looks at the photograph now, it invokes a different kind of nostalgia.

“It brings to mind the memories of all of the women that I met and knew,” she says, “and I wonder where those women from that photograph are now? What are they doing, who remembers them, who knows their names?”

The Smithsonian’s senior curator Bill Pretzer hand-selected Jones’ photo to be part of the exhibition, “A Changing America: 1968 and Beyond,” now on view at the National Museum of African American History and Culture. The wall-size display confronts visitors as soon as they enter the space. “Women's participation and the issue of gender equality ebbed and flowed within the Panthers’ history. It didn't simply improve or get larger, or devolve and get worse, it goes up and down,” he says of the photograph’s inclusion. “I think at the time and even since, the popular public image of the Black Panther Party as a super masculine group of men who were violent and fought the authorities pervades public sentiment. This image contradicts that dramatically and effectively.”

Ask ten different people to explain what The Black Panther Party was and you’re likely to get ten wildly different answers. Originated in October 1966 by Newton and co-founder Bobby Seale, it was an organization invested in resisting government oppression and police brutality. Whether that was perceived as political or socialist or Marxist or nationalist or all of those things, it created self-determination and community-based solutions under the auspice of “power to the people.” Its membership grew ferociously from its first chapter in Oakland to more than 2,000 members by 1968, clustered in more than 30 chapters in cities across the country and eventually the world. The civil rights movement’s methodical disobedience provided a stark contrast for the party’s controversially militant, sometimes confrontational revolutionary agenda.

A one-time political prisoner and former leader of the Black Panther’s New Haven, Connecticut chapter, Huggins can't recall if she was at that Oakland rally. If she wasn't, she says, she was somewhere else doing a similar thing. For the ten months that Newton awaited his proceedings, rallies rippled across the country to oppose his prosecution and later, his incarceration. One at the Oakland Arena on his 26th birthday drew 6,000 people and, when his trial began on July 15, 1968, more than 5,000 protestors and 450 Black Panthers stood on the courthouse grounds in support.

A month after the photo was taken, Newton was found guilty of voluntary manslaughter, and sentenced to two to 15 years, but the Free Huey movement didn’t end with his imprisonment. Buttons, banners and flyers emblazoned with the picture of a solemn Newton sitting in a wicker chair with a spear in one hand and a shotgun in the other magnetized new Party recruits—intelligent, politically and socially astute, and young. The average age of a Black Panther member was just 19. And half of them were women.

By that time, 1968 had already been electric with shared pain and expressions of fury. In April, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., was assassinated, igniting demonstrations and riots in more than 100 cities. Two months later, Robert Kennedy was similarly gunned down, and Vietnam War protests rocked the nation. At the same time in local communities across the U.S., law enforcement violence against the Black Panther Party had escalated, both in volume and viciousness.

The Ten Point Program, a platform of demands outlined by Newton and Seale, insisted on an immediate end to police brutality and the sanctioned murder of black people. Newton became the symbol of the very thing he was fighting to change—a black man centered unjustly in the crosshairs of governmental attack—and as more male members were profiled, killed and imprisoned, plucked off one-by-one as casualties of a domestic race war, black women in the party kept the work going.

“They were fighting for their lives, they were fighting for their loved one’s lives, they were fighting for their children's lives. They were motivated by the fact that the black community was under assault and it was time to make a difference. It was time to change things,” says Angela LeBlanc-Ernest, co-founder of the Intersectional Black Panther Party History Project, a collaboration of scholars and filmmakers who collect stories, archive information and shape the narrative of women in the BPP. “So Huey Newton became the face not just of Free Huey rallies—even though, yes, they wanted him freed—but he represented this person who dared to stand up and say, ‘No. You're not doing this to us anymore.’”

The outcry around Newton’s case elevated him to near-martyr status in a revolution that seemed more feasible almost daily. The immediate gratification of confrontation and self-made justice were attractive, particularly compared to the nonviolent demonstrations that were too humiliating, too obsequious, too slow to produce results for many coming of age in the tumult for basic civil and human rights. The Black Panther Party became a source of tactical empowerment, Huey Newton became a folkloric hero and his imprisonment became a cause célèbre.

“It’s time to pick up the gun. Off the pig!” the five women sang in unison. With fists punched into the air above them, they shouted, “Free Huey!” to the crowd.

“Free Huey!” the crowd shouted back.

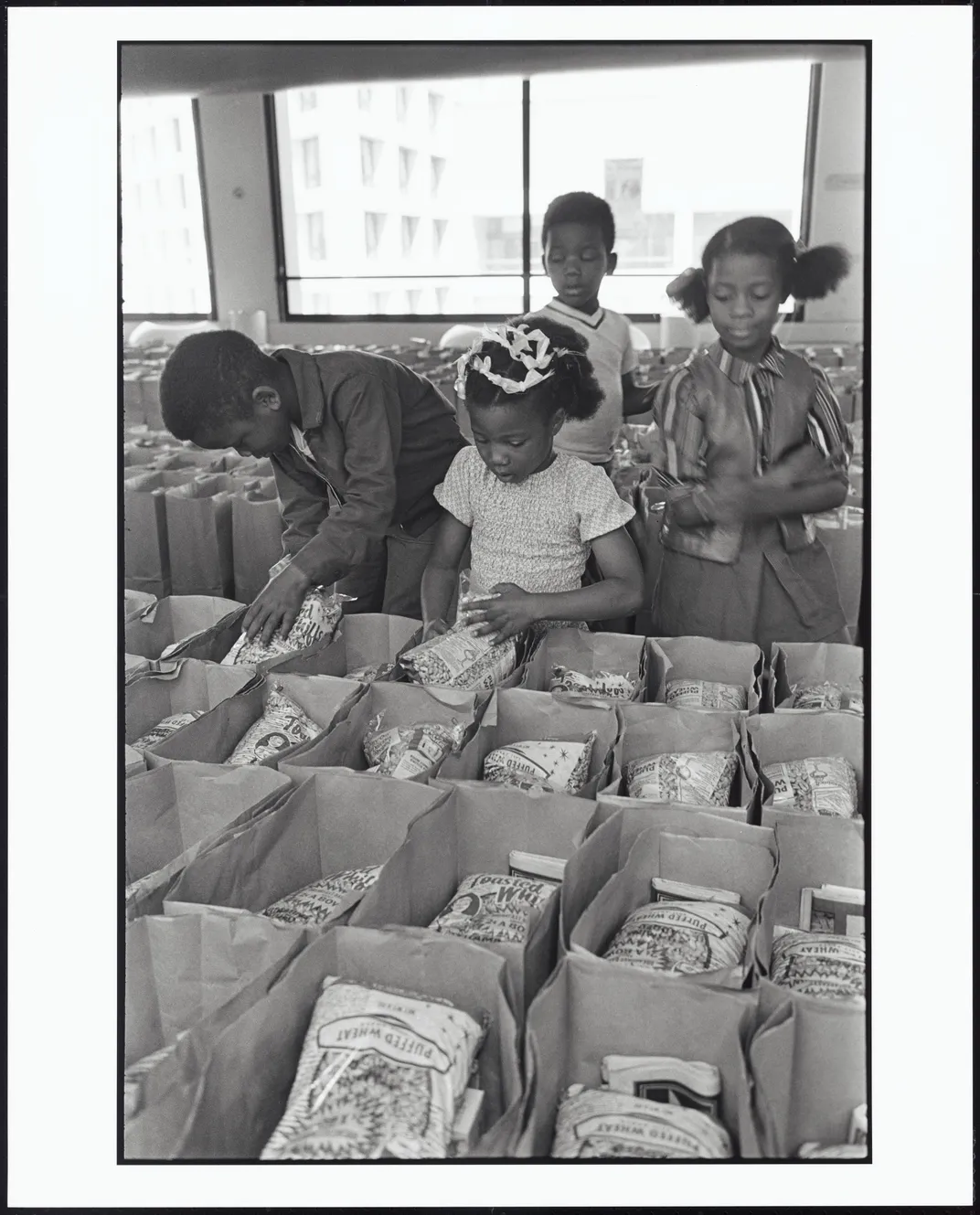

The women in the photo—Delores Henderson, Joyce Lee, Mary Ann Carlton, Joyce Means and Paula Hill—are not names that are widely recollected in the retelling of the Black Panthers’ legacy. They represent a segment of the party who often worked 17, 18, 19-hour days to actualize its vision. History calls them the “rank and file,” members who didn’t individually dominate headlines or generate media sound bites, but they were the soul of daily operations who executed the public-facing strategies and later, the community survival programs.

Some rallied, some handled administrative duties, some worked armed security, some served as organizers. Some worked on production, design and distribution of the newspaper, The Black Panther, an exhausting, near 24-hour operation masterminded by artist Emory Douglas. All sacrificed something of themselves and their personal well-being as BPP members. They moved the organization forward as they navigated the complexity of internal conflict, misogyny and mistreatment, and dichotomous ideologies that pitted armed revolution against community organizing. Whatever their role, they showed up to empower people who looked and lived like them.

“There was no one way to be a Black Panther Party woman. They came from all walks of life, and they entered and exited the party at different times,” says LeBlanc-Ernest. “There was a cultural moment happening and the women in that photo reflect its youthfulness and willingness to make a difference. If you look at the stance they're taking, their fists in the air, there's a unity and uniformity.”

Delores Henderson, pictured third from the left in the black and white dress, was 17-years-old and just graduated from Grant Union High School in Del Paso Heights when she learned about the Sacramento chapter founded by captain Charles Brunson and his wife and BPP communications secretary, Margo Rose. Unlike many of her fellow members—“comrades,” as she calls them—who were full-time college students, Henderson had just started a new 9-to-5 job at Pacific Bell. She was a working woman with a set schedule. Still, she was curious about the Panthers. When her friend Joyce Lee said, “Let’s go see what they're talking about,” Henderson agreed.

“I liked what they said. I wasn't having good feelings with white people in Sacramento. I was eight or nine when we moved there from Portland, Oregon, and as soon as I started school, I was being called a black ghost,” she remembers, along with other racial epithets. “People said, ‘don't let them call you that,’ so I was fighting almost every day, getting into trouble. When I got older, I realized that Sacramento—and I’ll say it to this day—is the most prejudiced place I have ever been. It was absolutely horrible.”

She and Lee joined in 1968 to be part of the hands-on effort to lessen the daily stresses of being black. On workdays when she couldn’t be there, Henderson donated money to help buy supplies that would serve the record numbers of students in the Panther’s before-school breakfast program at Oak Park United Church of Christ. Her weekends were dedicated to whatever her chapter needed her to do: sell newspapers, attend events, go to the firing range and learn self-defense techniques in case of combat. Her involvement in the Party wasn’t something she hid, but it wasn’t something she advertised either.

Once, after she patrolled the funeral for George Jackson, an activist and fellow Party member assassinated while serving a year-to-life sentence for armed robbery, a Pacific Bell co-worker came to her, excited. “She said, ‘I saw you on TV!’ I shook my head. ‘Uh-uh. You didn’t see me. You made a mistake,” laughs Henderson, now 68, retired and living in Krum, Texas, 45 miles outside of Dallas. Black women have historically established a definitive separation between their work selves and their authentic selves, and Henderson’s involvement in the most militant black group of its time made that duality even more essential.

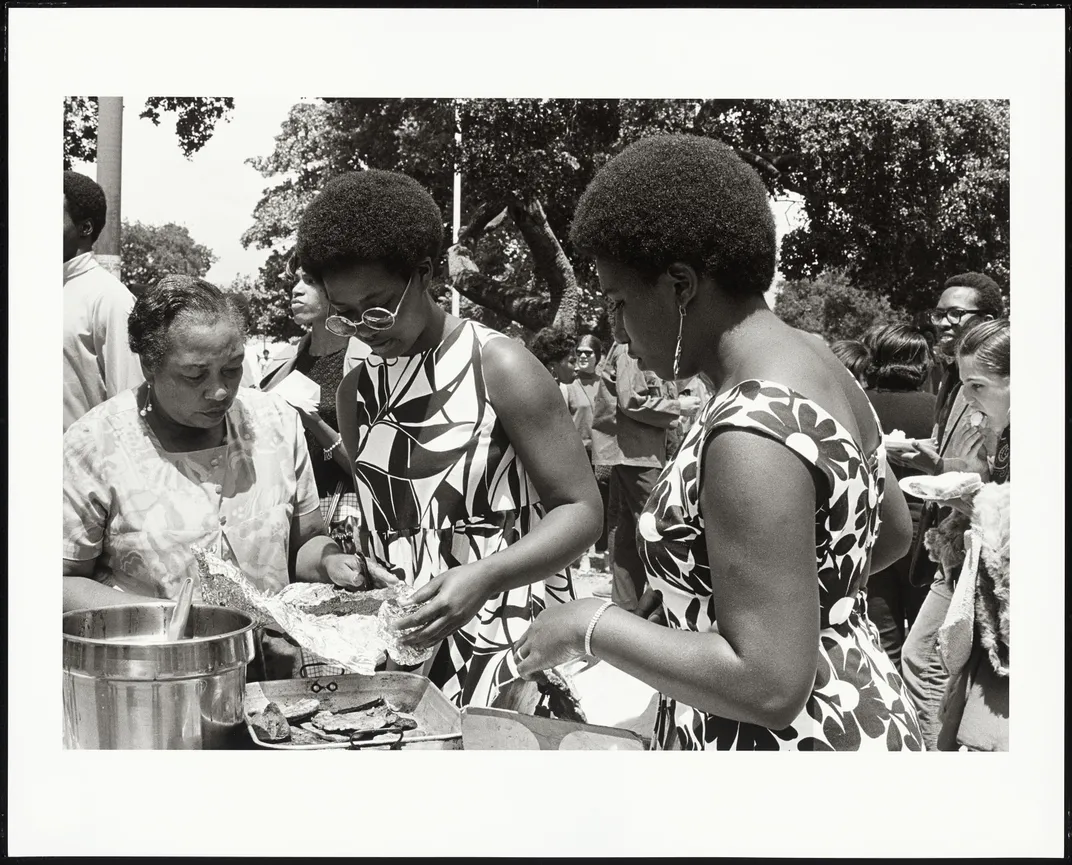

Like the anatomy of any other organization, each section of the Black Panther Party demanded a different skill set. How did they get thousands of people to come to their rallies in an era well before the connectivity of social media? They hit the streets, canvassed neighborhoods, talked to residents, shared what’s going on, listened to their questions and concerns. They organized across multiple chapters, some members coming from as far as San Diego nearly 500 miles away. It was a study in how to market an event when the phrase social media still meant face-to-face conversation and putting information squarely in folks’ hands.

On the day of the Oakland rally, Henderson piled into a car in Oak Park and roadtripped the 90 minute-drive with her fellow chapter members. It was a peaceful atmosphere with food, music and people of all races, she remembers, and she stood shoulder-to-shoulder with a line of other women all dressed in individualized interpretations of the Panther’s signature all-black clothing. A rally was a political stirring as much as it was a community event, and Sharon Pinkney and Shirley Finney, two of the chapter’s first female members, addressed an eager audience alongside Brunson. When he finished, Henderson says, Brunson told Bobby Seale that some sisters from Sacramento wanted to say something.

Seale furrowed. “’What the f*** are they gonna do?’” he said, half-asking, half-dismissing. Reluctantly, he allowed them to step forward and sing. “We were so scared. If you look at the other pictures, we were standing stiff at attention,” Henderson says.

She guesses they were on stage for about 20 minutes. They’d rallied the crowd in their own way and conveyed the central message in their own voices. When they walked off, Seale conceded. “OK, that wasn't bad,” he said. “More power to the sisters.” In that small, isolated instance, they needed to prove themselves and they did.

Their applied passion hit its target in a far-reaching impact. Newton’s conviction was overturned by the California Court of Appeals in May 1970, citing several mistakes, most notably the presiding judge’s failure to properly instruct jurors. After nearly two years in California Men's Colony in San Luis Obispo, Newton walked out of the same courthouse where he’d been led away. He was a free man released on $50,000 bail. When he strode outside, he stripped off his gray, prison-issue shirt and shouted to the supporters who’d been gathering in front of the building since the early morning: “You have the power and the power is with the people.”

When the photograph went on view at the Smithsonian, friends who’d visited before her told Henderson about it, but she wanted to see it for herself and traveled to Washington, D.C. Looking at that image more than 50 years after she lived it brought her to tears. “I have no children, so I tell my nephew and his kids, ‘Auntie Dee left y'all something.’ All of my memorabilia is going to them. This time and contribution is what I had to offer. And he said, ‘Well, just being in the Smithsonian is enough.’”

In 1970, police teargassed, raided and riddled the Sacramento BPP headquarters with bullets. No one was killed, but the office was destroyed, donations for the breakfast program were ruined and membership splintered to other chapters. Henderson never joined another activist outfit, and she folded that part of her personal history away. Facebook helps her keep up with what this comrade or that one is doing now and she had a good time in 2016 at the celebration that honored the Black Panthers’ 50th anniversary. She saw Bobby Seale there and took the opportunity to remind him of that hard, harsh thing he’d said when she and her sisters were preparing to address the rally that day in 1968. They laughed together about it, a joke now among two people who’ve shared an uncommon experience.

The movement to free Huey was an extension of the work Black women have always done—regenerating hope when hopelessness is easier, giving the best parts of themselves for the greater good, organizing collective resources for the betterment and future of whichever family, community, entity or group they thrust their power behind.

“When I say that women ran the Black Panther Party, I'm not bragging. It wasn't fun, it wasn't cute. It was dangerous and it was scary,” says Huggins. “The work that women did held the Black Panther Party together. If Huey were alive, he would say that. Bobby Seale is still alive and he says that all the time. There's nobody that would refute it. It was a fact.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/janelle.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/janelle.png)