Raoul Wallenberg’s Biographer Uncovers Important Clues To What Happened in His Final Days

Swedish writer Ingrid Carlberg investigates the tragedy that befell the heroic humanitarian

:focal(668x229:669x230)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b5/db/b5dbc2cb-3893-458e-a8d6-af317920b37d/na003642web.jpg)

On the morning of January 17, 1945, four days after the Red army reached eastern Budapest, Raoul Wallenberg’s car was under escort by three Soviet officers on motorcycles. They parked outside his most recent residence, the magnificent villa that housed the International Red Cross.

Wallenberg stepped from the car.

He was in excellent spirits and engaged in his usual witty banter. Those who encountered him during this quick stop on Benczur Street assumed that his conversations with the leaders of the Soviet forces east of the City Park, regarding a cooperative plan to ensure aid, must have gone well.

Today, 71 years after Wallenberg was apprehended that day in Budapest and later imprisoned by the Soviet military in the Lubyanka prison in Moscow, the finite details of the last days and the circumstances of his tragic death have long been mired in mystery and intrigue.

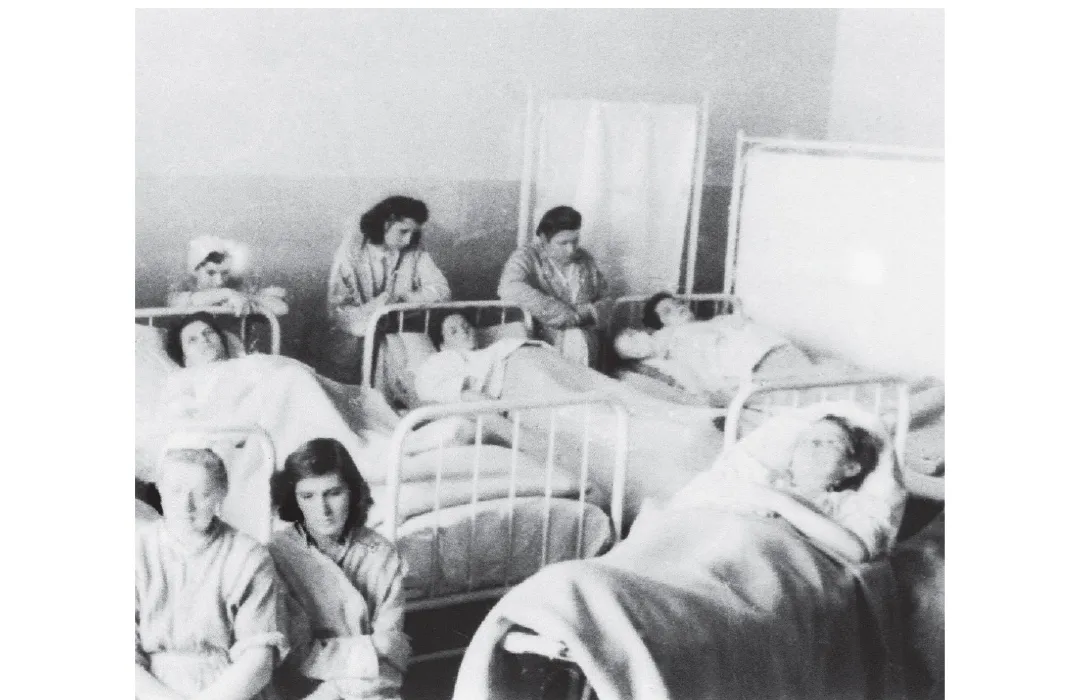

The Swedish humanitarian, who managed to save thousands of Hungarian Jews from the Holocaust by employing hundreds of them in various office locations throughout Budapest, delivering a wide range of services from shelter and food rations to medical care, as well as issuing protective documents and security patrols, is remembered the world over for the heroism of his selfless courage.

My 2012 biography on Raoul Wallenberg, which will be released in the United States in March, uncovers among other things much of the story of the final days. As a result of my extensive research into his last few hours as a free man, as well as my investigation into the morass of Soviet lies and shocking Swedish betrayals that followed his imprisonment, I was able to finally piece together the series of events that explain why Raoul Wallenberg met his tragic destiny and never became a free man again.

Wallenberg had arrived in Budapest six months earlier on July 9, 1944. A series of factors led to his hasty selection to a diplomatic post as Deputy Secretary at the Swedish Embassy, including a directive from the United States government for an important rescue mission of the Hungarian Jews.

In the spring of 1944, German troops had marched into Hungary and in a final act of chilling evil, enacted World War II’s most extensive mass deportation. In just seven weeks, more than 400,000 Hungarian Jews were transported to Auschwitz, the vast majority directly to the gas chambers.

At the time, the United State’s diplomatic situation was precarious; its leaders had finally stirred from their original decision paralysis in the face of the unfolding Holocaust, but Secretary of State Cordell Hull had few options for rescuing the Hungarian Jews since the country was already engaged in the war. He turned to the neutral country of Sweden, asking for unofficial cooperation in a rescue mission. If the Americans were to foot the bill, would Sweden, who had diplomats in place, send additional personnel in order to administer such an operation? And if so, who should be selected?

Raoul Wallenberg was employed at a Swedish-Hungarian import company and had been to Budapest several times. But most importantly, his employer had offices located in the same building as the U.S. Embassy in Stockholm. When offered the job, he did not hesitate.

The final months leading up to his January capture had been a bitter struggle.

Wallenberg and his 350 employees, who by the end of 1944 were part of his extensive organization, had long since outgrown the Swedish Embassy and spilled into a separate annex with its own offices.

Tens of thousands of Jews were living under severe circumstances, but still relatively safe, in the separate ”international ghetto” created as a safe zone by the diplomats of the neutral countries. These Jews escaped the starvation of the central ghetto, and the protective papers issued to them by the neutral nations still afforded them a certain amount of protection on the streets.

But the questions persisted: Could they manage to hold out until the Red Army, the USA’s allied partner to the east, arrived? Why was liberation taking so long?

According to what Wallenberg later told his fellow inmates, his military escorts reassured him that he was not under arrest. He and his driver were placed in a first class compartment on the train for the journey through Romania and were allowed to disembark in the city of Iasi in order to eat dinner at a local restaurant.

Raoul Wallenberg spent the rest of the train trip working on a “spy novel.”

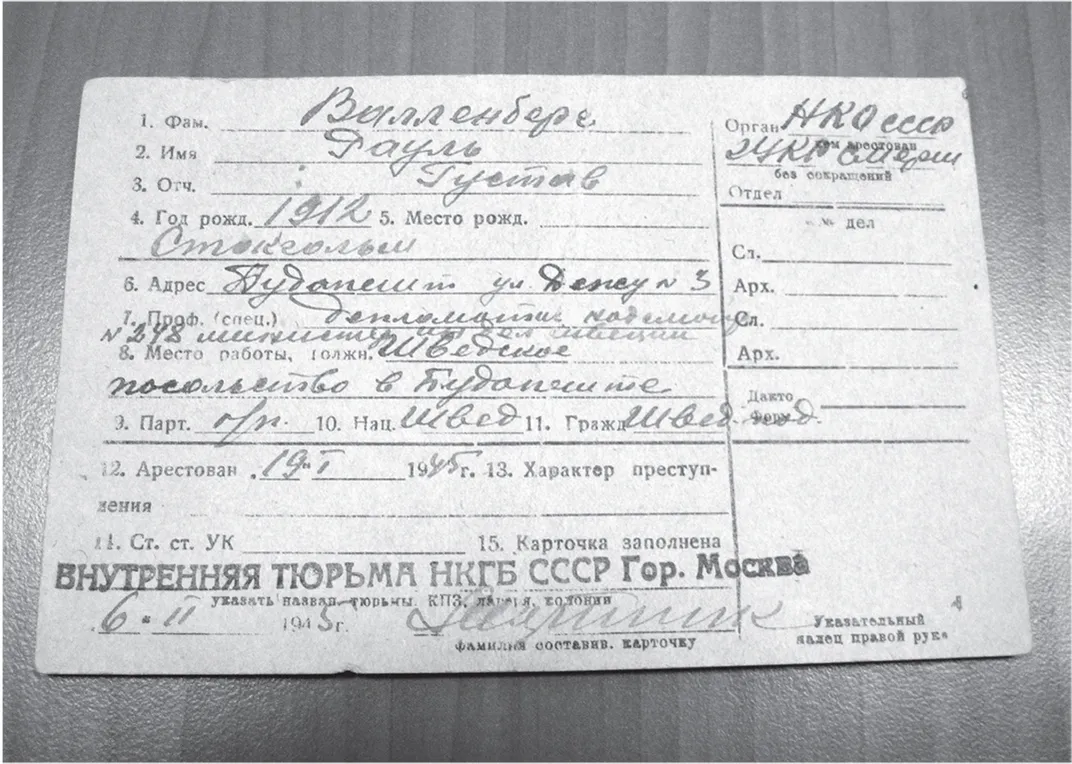

Archival records of the Soviet prison system registry show that the Swedish diplomat was registered as Raoul Gustaf Wallenberg and designated as a “war prisoner.”

In the prison register Wallenberg was called a diplomatic “observer,” not as was customary, an “official”—a detail that indicates Soviet suspicion. When I held his original prison card in my hand a few years ago, during a meeting in Moscow with the chief of the FSB Archives, I could see with my own eyes how the slot designating his “crime” was left blank. I also noted that no fingerprints were taken.

Soon after his disappearance, rumors that Raoul Wallenberg was not in Soviet custody began to be reported on Soviet-controlled Hungarian radio channels, and rumors of his death were circulated as cocktail fodder at diplomatic receptions.

Wallenberg was said to have died in Hungary amid the January tumult—perhaps in an accident, a robbery or in a bombing raid.

Sadly, this disinformation quickly took hold at the Swedish Foreign Ministry and by the spring of 1945, the prevailing widespread conviction of his demise weakened any remaining official diplomatic efforts to free him. The Swedish government preferred not to raise uncomfortable questions over Wallenberg’s disappearance for fear of inciting the wrath of Joseph Stalin. Why risk Soviet anger towards neutral Sweden if Raoul Wallenberg was already dead?

Raoul Wallenberg was not the only neutral diplomat who accomplished rescue missions in Budapest that autumn. Neither was he the only one who longed for aid from the Russians.

When the Red Army was finally within reach, Wallenberg asked some of his coworkers to develop a plan, in part to save the increasingly vulnerable central ghetto in Budapest and in part to reconstruct Hungary after the war. He intended to suggest a cooperative effort to the Soviet military leaders as soon as the first troops arrived.

Wallenberg seems not to have been aware of the growing animosity between the Soviet Union and the United States. With the end of the war in sight, Joseph Stalin increasingly expressed disdain for the United States and Great Britain, worried that his Western Allies had gone behind his back to negotiate a separate armistice with Germany.

Significantly, Soviet foreign affairs leaders had also begun to reformulate their politics toward Sweden. The Kremlin reasoned that the time had come to punish the supposedly neutral country for its German-friendly policies. Among other things, the very day of Wallenberg’s arrest, on January 17, the Soviet Union shocked Sweden when it declined a proposal for a new trade agreement, which the Swedes believed was simply a matter of formality.

When Wallenberg returned to Budapest that morning to pack up his things, he was under the impression that he was to be a guest of the Soviets. In fact, he was told that the Soviet officers would bring him to Debrecen in eastern Hungary, where the commander of the 2nd Ukrainian Front General Rodion Malinovsky would receive him to discuss the suggested cooperation.

However that same day, an order for Wallenberg’s arrest, signed by deputy defense minister Nikolai Bulganin, was issued in Moscow and also sent to the Hungarian Front.

Encouraged by what he thought lay before him, Wallenberg went to his office to express his great joy over the fact that the International ghetto had just been liberated and that the majority of the Hungarian Jews living there had been saved. But since he was in a hurry, he told his coworkers that they would have to wait to describe how this came about until he returned from Debrecen.

He said that he likely would be gone for at least a week.

Instead on January 25, following orders from the Kremlin, he and his driver Vilmos Langfelder were transported to Moscow by train.

We know today that Raoul Wallenberg was, in fact, alive in Soviet prisons at least up until the summer of 1947. Still it took until 1952 before Sweden issued a formal demand for the diplomat's return for the first time. During those seven years, the Swedish government simply took the Soviets at their word: Wallenberg was not in Soviet territory and he was unknown to them.

In the fall of 1951, the situation changed. The first prisoners-of-war were released by the Soviet Union and an Italian diplomat Claudio de Mohr said that he had had contact with Wallenberg at Lefortovo prison.

But the following February, when Sweden issued their first formal demand for the return of Raoul Wallenberg, the Soviets stonewalled them by repeating the lie.

Then, following Stalin's death in 1953, thousands of German prisoners-of-war were released, and detailed witness accounts surfaced, describing encounters with Raoul Wallenberg in Moscow prisons.

In April 1956, on a visit to Moscow, Prime Minister Tage Erlander presented the Soviet Union’s new leader Nikita Khrushchev with a thick file of evidence.

Faced with the new Swedish evidence, Khrushchev realized that he had to acknowledge the arrest, but how? The search for a new lie started.

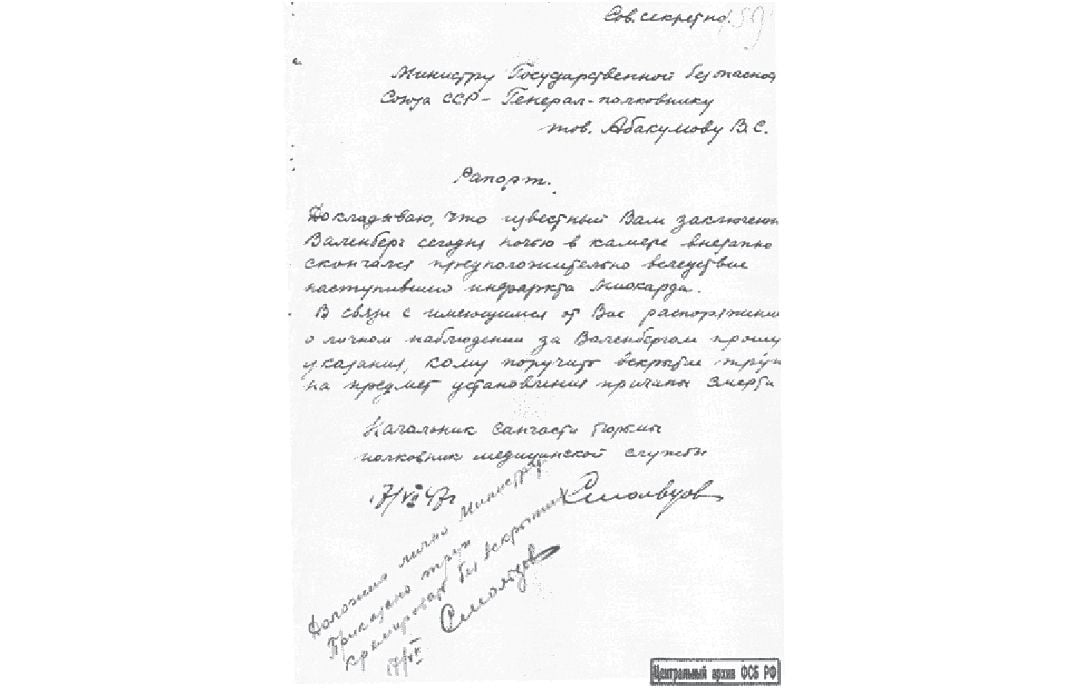

Internal Soviet Foreign Ministry documents reveal that later that spring, Soviet officials were put to work in the hospital archives to search its documents for a cause of death that could appear as true. The first suggestion was to tell the Swedes that Wallenberg died of pneumonia in the Lefortovo prison in July 1947, but throughout the process both the cause of death and the location were changed.

To this day, the formal Soviet report that finally was presented in 1957 remains the official Russian account of the case—Raoul Wallenberg died in his cell in Lubyanka prison on July 17, 1947, two and a half years after his initial arrest. Cause of death: heart attack. A handwritten “death certificate” is signed by the head of the infirmary A. L. Smoltsov.

In 1957 the Soviets also insisted that they had thoroughly investigated every Soviet archive, but that the handwritten “Smoltsov report” was the single remaining evidence of the Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg.

Decades later, Glasnost not only brought the Soviet Union down, but also opened Soviet archives to a combined Swedish-Russian working group, with the aim to put an end to the Wallenberg case by answering the lingering question: What happened to him?

Suddenly substantial documentation of Wallenberg’s imprisonment in the Soviet Union emerged from the archives and was made public.

Still despite a ten-year Swedish-Russian investigation, nothing could convince either side. The archives closed again and Russia continued to say that Wallenberg died at Lubyanka July 17, 1947. But Sweden argued that the “death certificate” was not evidence enough.

Since no charges were ever brought against Raoul Wallenberg and no trial was ever held, the real reasons for the arrest also remain unknown. Today, Russian Security Service archivists assert that no reports from any of Raoul Wallenberg’s interrogations in Moscow prisons exist. Such documents have in any case never been made public. The only thing we know for sure is when he was interrogated and for how long.

Now, the Russian account is more disputed than ever because of prison records that include an interrogation of an anonymous “Prisoner Number 7” that took place in Lubyanka on July 22 and 23 in 1947, five days after Wallenberg was reported by the Soviets to have died.

Some years ago, the head of the Russian security service archives established that this prisoner was “with great likelihood” Raoul Wallenberg, who was held in cell number 7.

This information is indeed difficult to combine with the official Russian “truth.” Not even in Stalin’s Soviet Union were interrogations conducted with the dead.

Raoul Wallenberg “with great likelihood” was alive on July 17, 1947. Moreover, given the different suggestions, we can be sure that the cause of death was not a heart attack.

The mystery remains. But should the Russian government ever decide to finally, after all those years, reveal the real truth, I am quite sure of its content: Raoul Wallenberg was executed in Lubyanka some time during the second half of 1947.

On the morning of January 17, 1945, when Raoul Wallenberg left Budapest with the Soviet escort, he unfortunately made the same mistake as numerous Swedish ministers and diplomats would make in the years to come: he believed what he was told.

On the way out of town, his driver slowed down beside the City Park. They dropped off a friend of Wallenberg's, who was not coming with him to see the Soviet commander in Debrecen.

The friend later described those last moments: ”We took a very fond farewell of each other and I wished him all the best for what under those circumstances could be quite a precarious journey. Then the car disappeared from view."

Swedish writer and journalist Ingrid Carlberg was awarded the August Prize for her 2012 book about the life and destiny of Raoul Wallenberg, an English translation will be released in the United States in March. Carlberg is a Smithsonian Associates featured guest speaker and will sign copies of her biography Raoul Wallenberg on March 23 at 6:45.