A Rare and Important Sculpture of Martin Luther King

As the nation pauses to honor the great Civil Rights leader, Charles Alston’s work at NMAAHC is one of his most prominent pieces

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/00/8e/008ec8aa-651a-4d50-950e-a9715b5f3963/2015160001web.jpg)

Less than two years after Martin Luther King, Jr was assassinated, the African-American artist Charles Alston received a commission from Rev. Donald Harrington for the Community Church of New York to create a bust of the Civil Rights leader for $5,000.

Alston, who was active in the Harlem Renaissance, was better known as both an abstract and representational painter. He had been the first African-American supervisor for the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project. But his 1970 bust of MLK, of which he made five casts, became one of his most prominent pieces.

The Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery commissioned one of the 1970 castings and lent the work to the White House, where it has stood in the library since 1990, the first image of an African American on display at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue.

When Barack Obama became the first black President in 2009, he brought the work into the Oval Office, replacing a bust of Winston Churchill that had been returned to the British Embassy. There it became a prominent work, seen in official portraits with visiting dignitaries and heads of state.

Now a second copy of the famous King bust comes to Washington for all the public to see close up.

On the eve of Martin Luther King Day weekend, officials from the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture are announcing the recent gift of one of the rare copies of the 1970 Alston sculpture of Martin Luther King, which will be on display when the new museum opens this September.

“We’re very excited to have it,” says curator Tuliza Fleming. “It really fits quite nicely into our mission.”

The sculpture is a gift from Eric and Cheryl McKissack of Chicago, who had purchased it from the N’Namdi Contemporary art gallery in Miami five years ago.

“We have a couple of other works by Charles Alston,” McKissack said from Chicago, where he is a principal in an institutional investment and management firm. “We are obviously fans of his work. We don’t have a very long history with this particular piece, but we felt it was such a significant subject as well as an important artist of color.”

It won’t be the first Alston for the new museum, either.

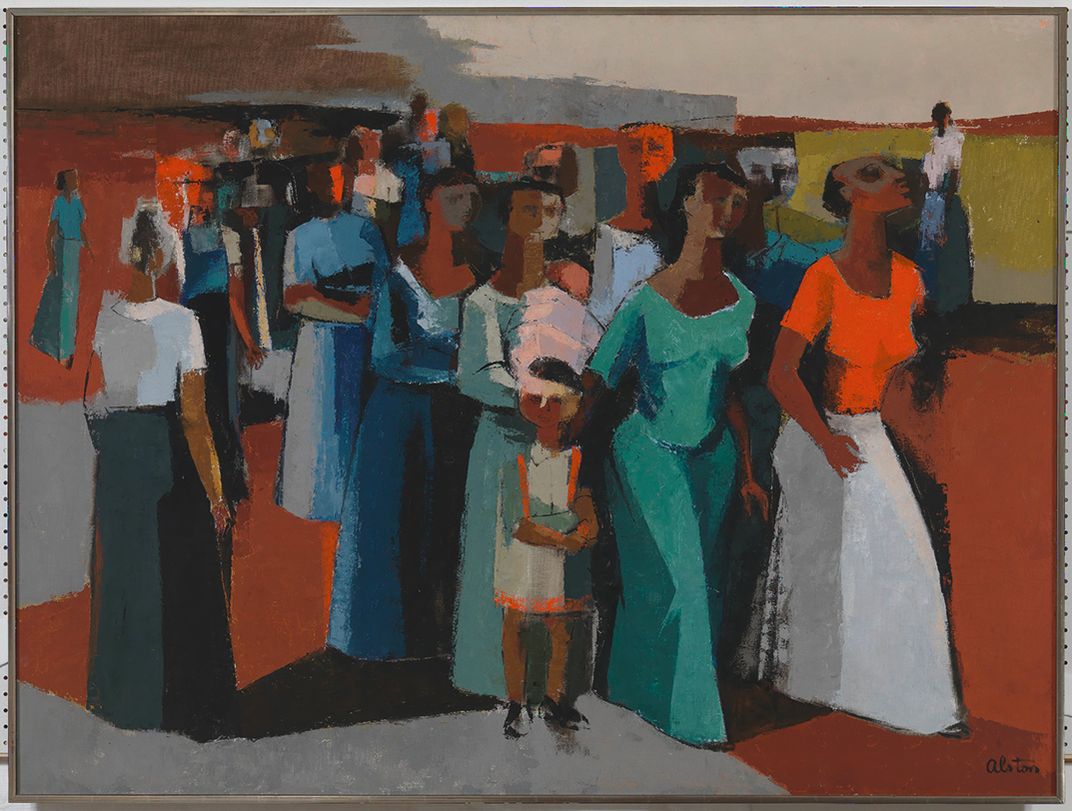

“We also have a painting by Charles Alston in this gallery called Walking,” says Fleming, “Inspired by the Montgomery, Alabama, bus boycott.”

Both the 1958 painting and the 1970 bust, which stands 17 inches high and mounted on marble, with the Civil Rights leader’s eyes gazing upwards, will be in the museum’s “Visual Arts and the American Experience” gallery, which itself is organized by themes, Fleming says.

“One of our themes is called ‘The Struggle for Freedom,’ and both Alston works will go there,” she says. “It’s really nice not only to have two works by this artist, but two works which reflect his social activism, and his life as an black artist.”

Fleming retrieved a quote from the artist, illustrator and teacher who was born in Charlotte, North Carolina in 1907, who died in New York in 1977 at age 69.

“He says: ‘As an artist, I am intensely interested in probing, exploring the problems of color, space and form that challenge all contemporary painters. However, as a black American, I cannot but be sensitive and responsive in my paintings to the injustice, and indignity and the hypocrisy suffered by black citizens.’

“This is a dated quote,” Fleming says, “but it really gets to the crux of these issues that African Americans face in this country and how artists engage in these issues of Civil Rights.”

McKissack said he was aware of the creation of Smithsonian’s latest museum and knew director Lonnie G. Bunch III when he was involved at the Chicago Historical Society.

“It’s such an important institution not just to African Americans, but to really have a complete telling of the history of our country that we really wanted to be supportive of it,” McKissack says. “I heard that this was of interest, so it came together.”

As an art collector, McKissack says he “many years ago became engaged in artists of color. Feeling that they were not always included in the canon and discussions and exhibitions I saw going to museums.”

McKissack himself is part of a storied African-American family.

“My grandfather and great uncle started the first African-American architecture and engineering firm in 1905,” he says. “My grandfather was the first registered African American architect that we’ve seen. I think he started around 1920. We have a history of our family being involved in building and trade going back to slavery.”

Having Alston’s dynamic King bust on display as part of the new African American History Museum for the public to see when it opens later this fall will be significant—nearly as much as the one that stands in the Oval Office, where, McKissack notes: “The King bust is adjacent to a bust of Lincoln—a juxtaposition that is really powerful as well.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)