Rare Chance in 2020 to See This Classic Danish Masterwork

At the Portrait Gallery, a new show gets at the visual heart of competitive camaraderie roiling within artist colonies

:focal(1799x971:1800x972)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/49/23/4923db8e-d041-491f-91b0-5c0511b5f051/exhig05_ancher_kunstdommere.jpg)

For centuries, artists have gathered together to share ideas, trade techniques, show support and to occasionally pose for one another. They have also been competitive rivals, sniping at one another in good-natured and not so good-natured ways.

So when a quartet of artists from a far-flung Denmark fishing village turned artist colony came together to see the unveiling of one painter’s portrait of another, there was enough skepticism, consideration and rumination to warrant a whole other work—Michael Ancher’s monumental 7-by-5 foot 1906 oil on canvas, Kunstdommere (Art Judges).

Ancher’s group portrait captured a handful of Danish cultural luminaries of Scandanavia’s Modern Breakthrough movement of the 1870s and 1880s, and that only helped to make it a beloved national masterwork.

Now, the artwork is the centerpiece of the third Portraits of the World exhibition at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery in Washington. The series borrows a key work from a chosen country, and surrounds it with augmenting pieces from the museum’s own collection. Earlier shows have showcased works from Switzerland and Korea.

In this case, the competitive camaraderie of the Skagen village artist colony is put in context with works that largely show artists working together in quite a different setting—the teeming studios of early 20th century New York City.

In Kunstdommere, Ancher, one of Demark’s best known artists, depicted the reactions of four notable figures—dramatist Holger Drachmann, artist Peder Severin Krøyer, artist Laurits Tuxen, along with Jens Ferdinand Willumsen, a younger artist.

Willumsen’s work would eventually encompass abstraction, but at the time, the Modern Breakthrough artists of Denmark were already making their mark with evocative, realistic depictions of everyday life and not just the usual romanticized views of royalty. That aim sparked their move to a remote fishing village to do their work.

“One of the things that’s so great about this painting is that it’s a mini history lesson on Danish culture,” says the Portrait Gallery’s curator of prints and drawings Robyn Asleson, who put together the show. “These are the greatest artists and literary figures in the country—all in this one, monumental painting.”

They are still well-regarded figures in their country. A profile of Ancher and his wife—from a portrait by Krøyer—was on the 1000 Danish Kroner banknote from 1998 to 2012.

Of the four in the painting, Tuxen, in his white suit and red beard, was the “royal portraitist of favor; he painted the royal court, he painted Queen Victoria,” Asleson says. “So he’s a little bit of the old school.”

Krøyer, by contrast was the epitome of the Modern Breakthrough. “Perhaps the most famous and loved artists in Denmark, with his scenes of fisherman and their lives of danger and hardship near the water. He is explaining to this group, this portrait we can’t see,” Asleson says.

Underlying the relationship among artists was competition, and some specific grousing about how long it took to sit for such a portrait. “That’s the tension that’s under the surface among these friends,” she says. “It’s like: ‘What’s taking you so long?’”

Asleson says she had hoped to augment the painting with examples from rural American arts colonies of that era, but found there were no portraits in their collection from communities in Ogunquit, Maine or Provincetown, Massachusetts.

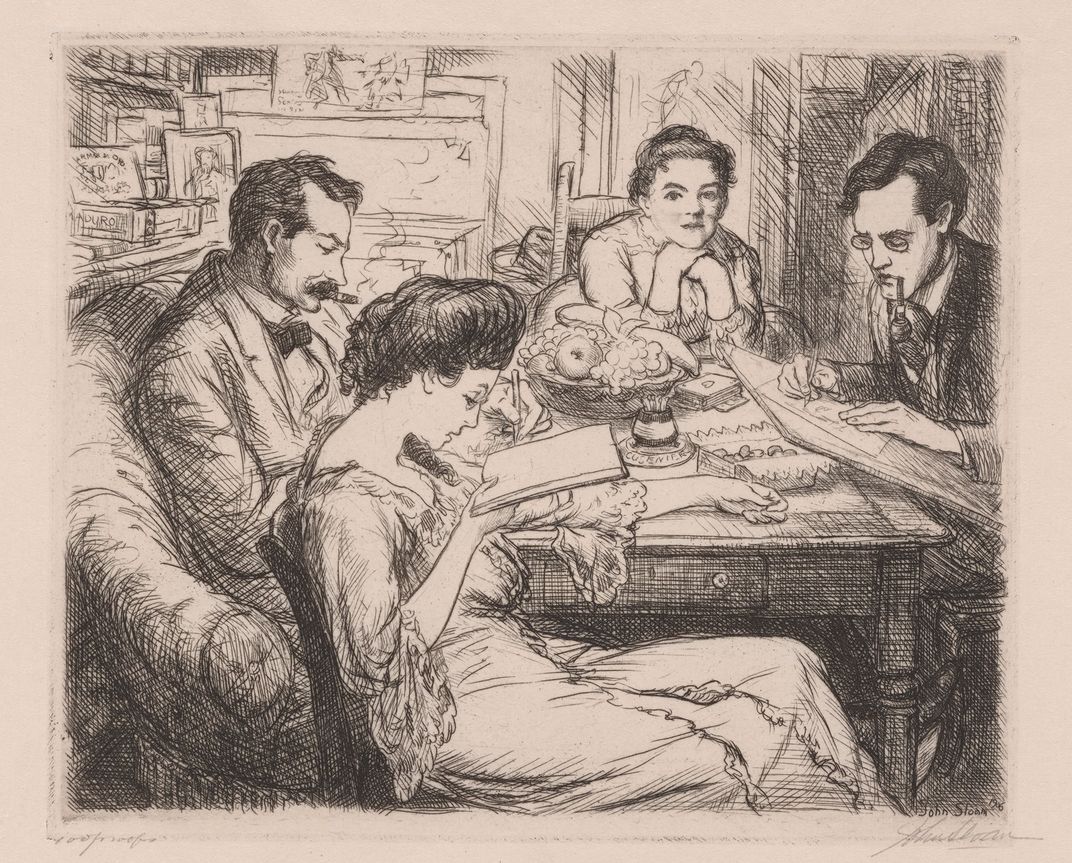

“Luckily we have all these great portraits of artists’ communities in New York,” she says. It includes the early Ashcan School of Robert Henri represented in a 1906 etching by John Sloan, who also appears in a Marion D. Freeman etching of a workshop at the Art Students League.

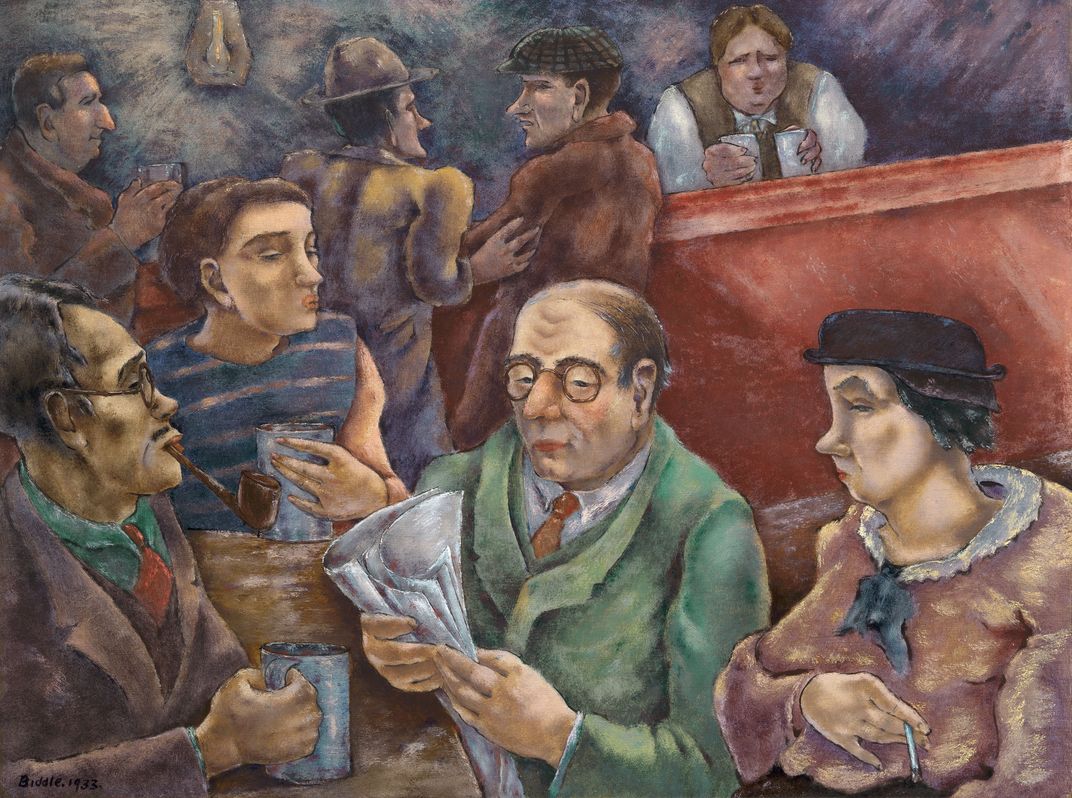

The painter George Bacon depicts his circle at a speakeasy in a 1933 painting that had been hanging at a government building until now. Peggy Bacon shows the Whitney Studio Club drawing class in a frenzy while things are calmer in Mabel Dwight’s 1928 lithograph of the Weyhe Gallery.

Alfred Stieglitz’s modern art circle is represented in a pair of works by Marius de Zayas and Francis Picabia sharply critical of Stieglitz’s perceived lack of forward movement.

American art’s own Modern Breakthrough arose from Abstract Impressionism, so there are a couple of striking Hans Namuth photographs from the early 1950s—one of Jackson Pollock, Barnett Newman and Tony Smith at Betty Parsons’ gallery and another of Elaine and Willem de Kooning with one of his works (as if to show that she’s not the model for his jagged abstractions of women).

De Kooning is celebrated further in a Red Grooms work that literally breaks through the picture plane with the bicycling artist giving his abstracted woman a ride on his handlebars.

The idea of art judges reflects some other events currently at the museum, where the juried triennial Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition is on display. A Bill Witt shot of Hans Hoffman in his Provincetown studio in the Portraits of the World show hangs quite near a shot from the same session in a photography show called “In Mid-Sentence.”

Portraits of the World: Denmark will hang through October. The Portrait Gallery established a connection with the lending Danish Museum of National History in Hillerød by offering in a return last winter a show of jazz portraits by Herman Leonard.

“We really hope that the art judges in the United States—the visitors to the gallery and the critics—will receive it positively,” Mette Skougaard, director of the lending museum said before the work was shipped.

Currently, to support the effort to contain the spread of COVID-19, all Smithsonian museums in Washington, D.C. and in New York City, as well as the National Zoo, are temporarily closed. Check listings for updates.“Portraits of the World: Denmark” is scheduled to remain on view through October 12, 2020 at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery in Washington D.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)