Rarely Seen 19th-Century Silhouette of a Same-Sex Couple Living Together Goes On View

A new show, featuring the paper cutouts, reveals unheralded early Americans, as well as contemporary artists working with this old art form

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e2/40/e240a63d-ab96-4a96-a56b-55250def2391/x1979325_sheldon_double-silhouette.jpg)

Among the dozens of works on display in a new show at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery is one that is possibly the first depiction of a same sex couple—the silhouettes of Sylvia Drake and Charity Bryant of Weybridge, Vermont, entwined in braided human hair that is also shaped into a heart.

“Can you imagine an oil painting of these two women from that era” asks Asma Naeem, the National Portrait Gallery curator of prints, drawings and media arts, who curated the new show Black Out: Silhouettes Then and Now and authored its catalog.

William Cullen Bryant, Charity’s nephew, wrote in 1843 of their relationship: “If I were permitted to draw aside the veil of private life, I would briefly give you the singular, and to me most interesting history of two maiden ladies who dwell in this valley. I would tell you how, in their youthful days, they took each other as companions for life, and how this union, no less sacred to them than the tie of marriage, has subsisted, in uninterrupted harmony for more than forty years. . . but I have already said more than they will forgive me.”

“Silhouettes allowed these kinds of stories to be told,” says Naeem. “It’s important to note that people of all backgrounds, of all sexual orientation, have been in this country from the very beginning. That allows us to tell that story.”

The bold new show about an old art form looks at its complex historical, political and sociological underpinnings. It is not only the first major museum exhibition to explore the popular art form of cut paper profiles, but the show also digs deeper into how quick and inexpensive process that offered “virtually instantaneous likenesses to everyone from presidents to the enslaved,” says the museum’s director Kim Sajet.

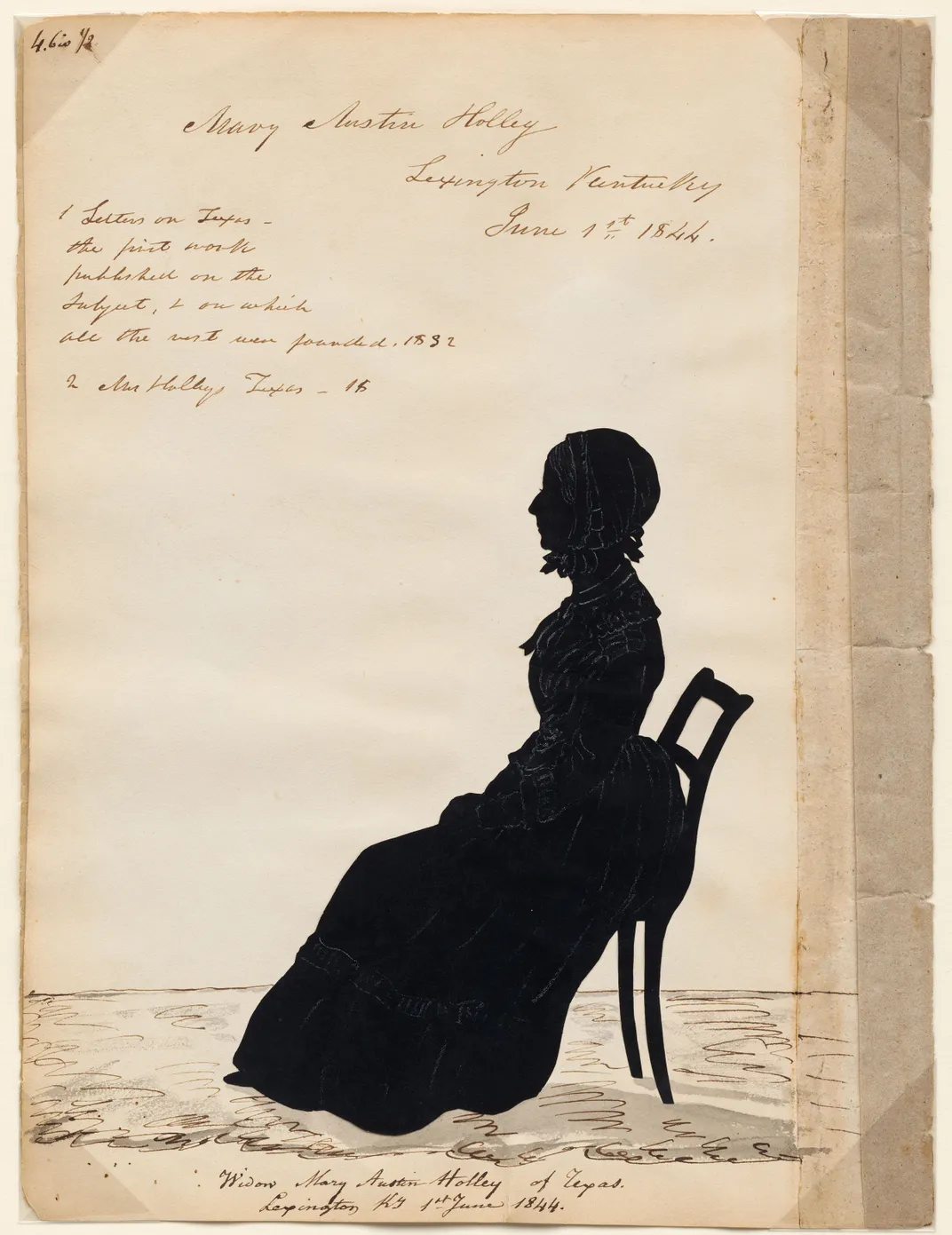

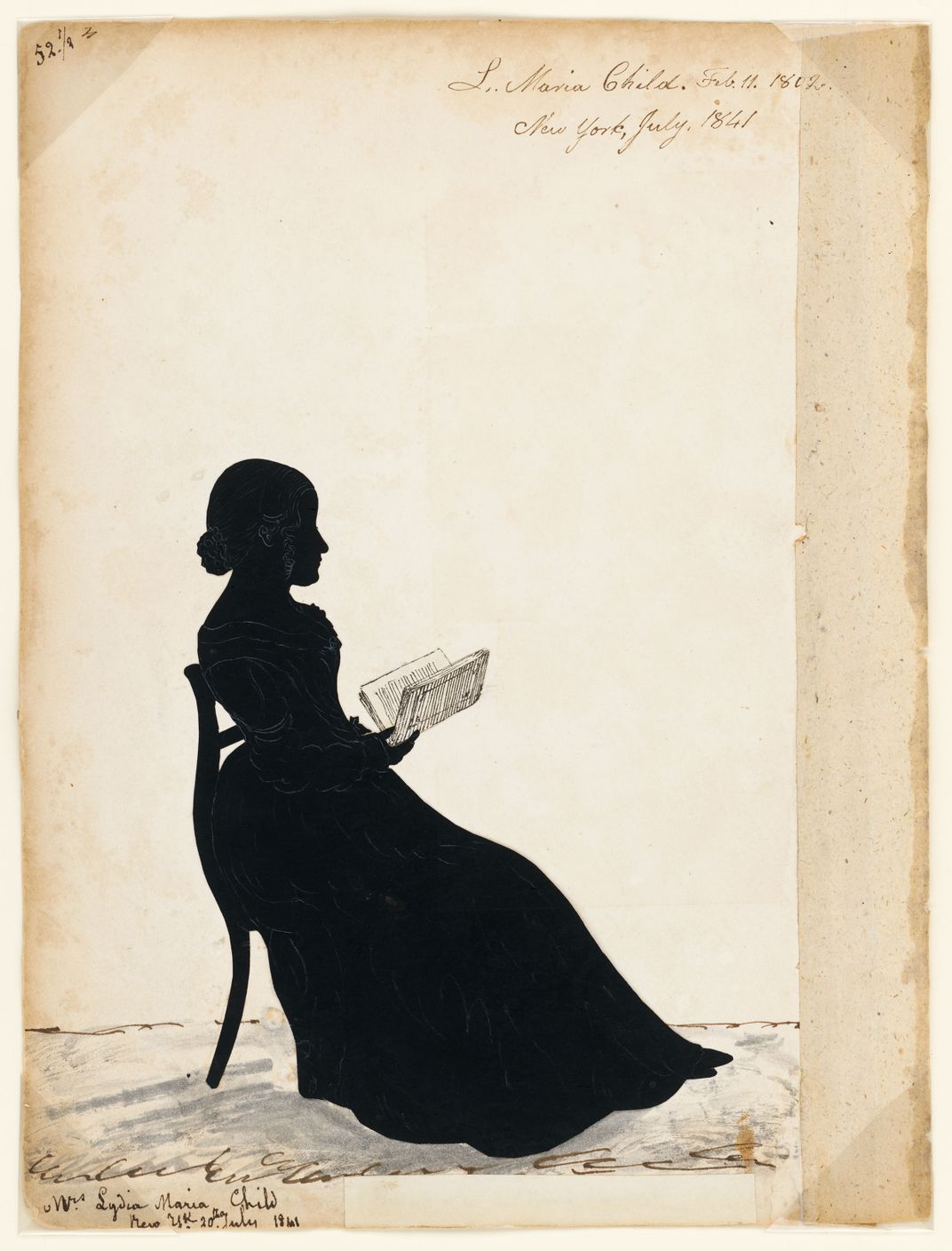

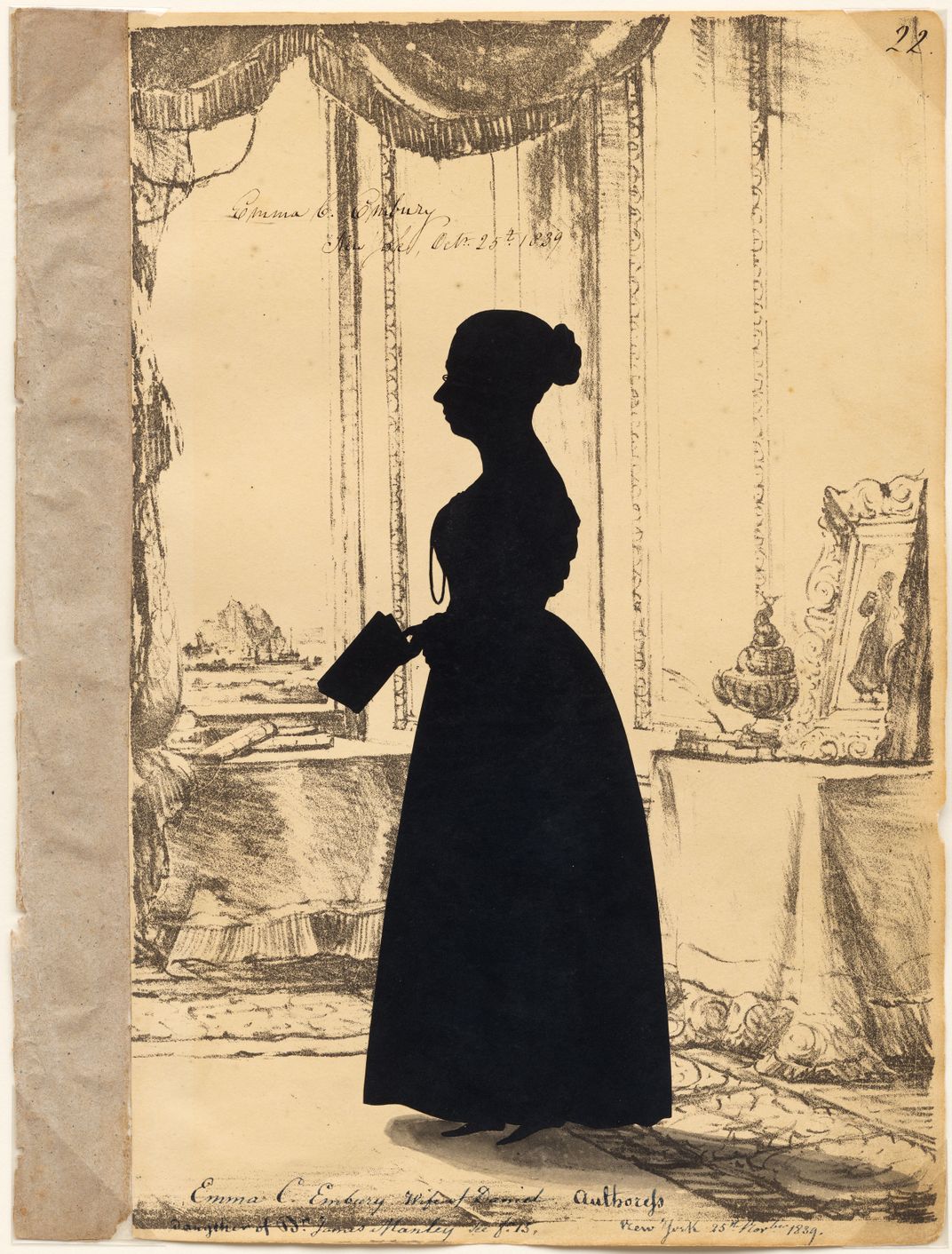

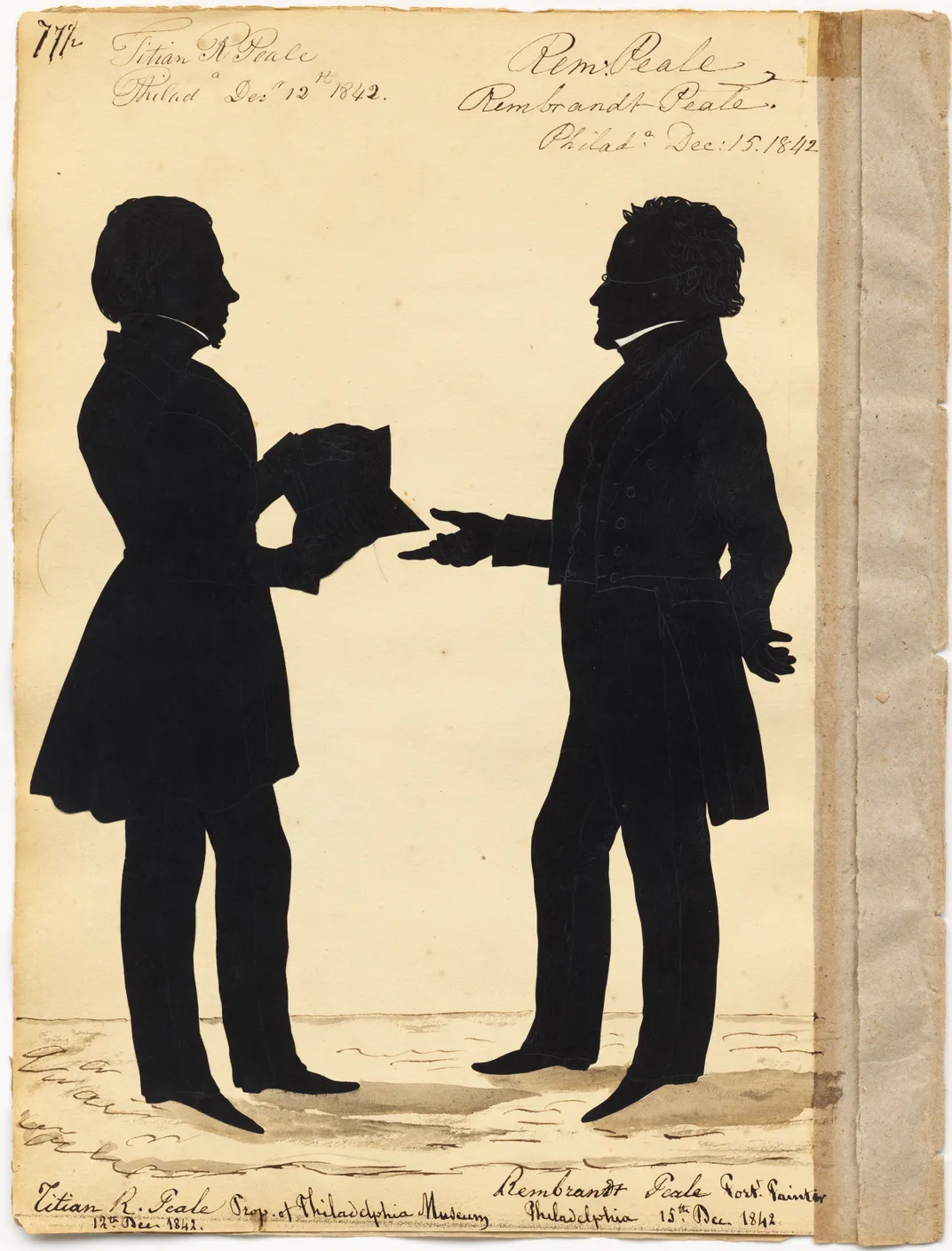

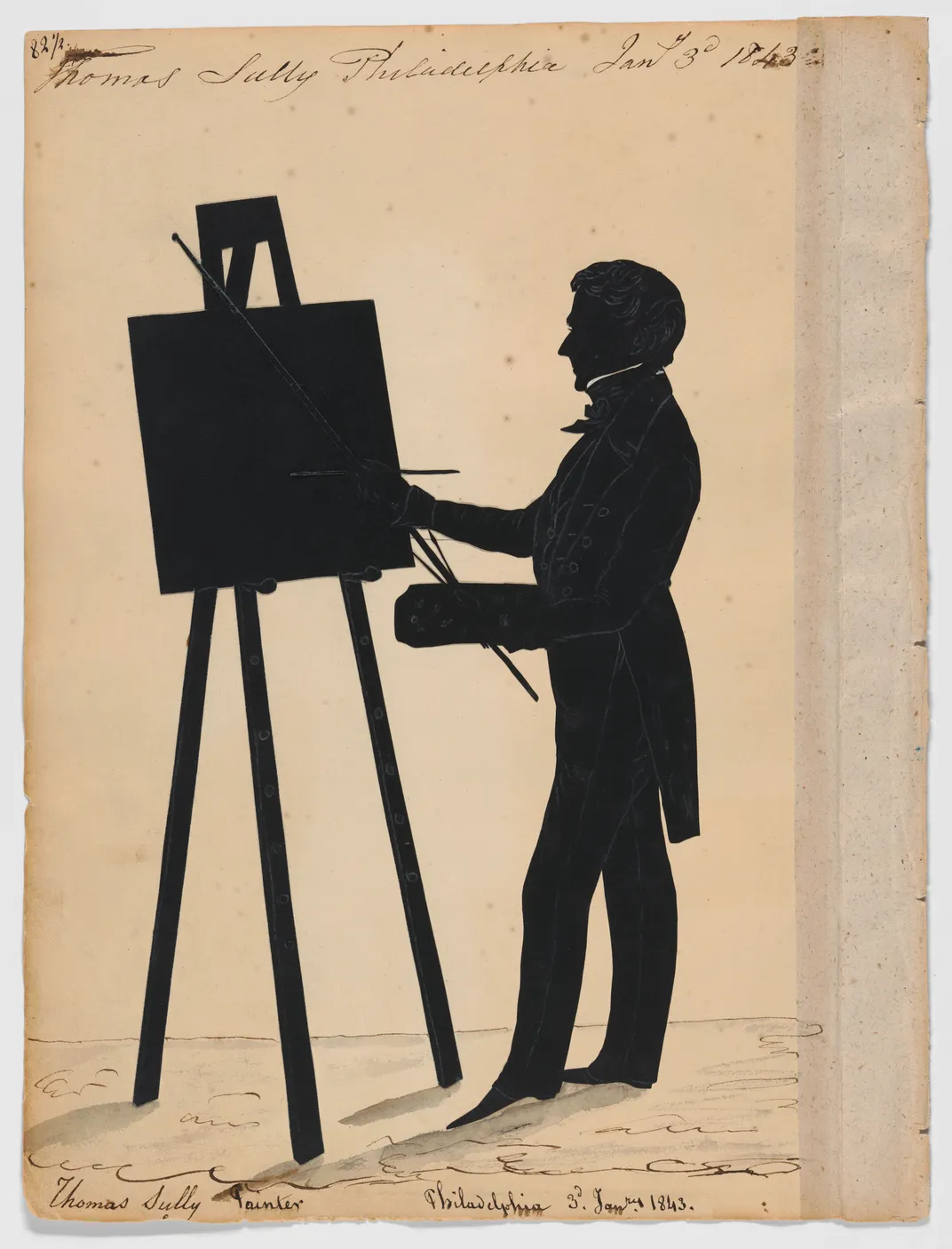

Indeed, a huge ledger containing the work of silhouette cutter William Bache, a collection of 1,846 profiles, begins with the side views of George and Martha Washington but also includes a wide swath of people from all socioeconomic status that Bache cut while working in his studio in New Orleans.

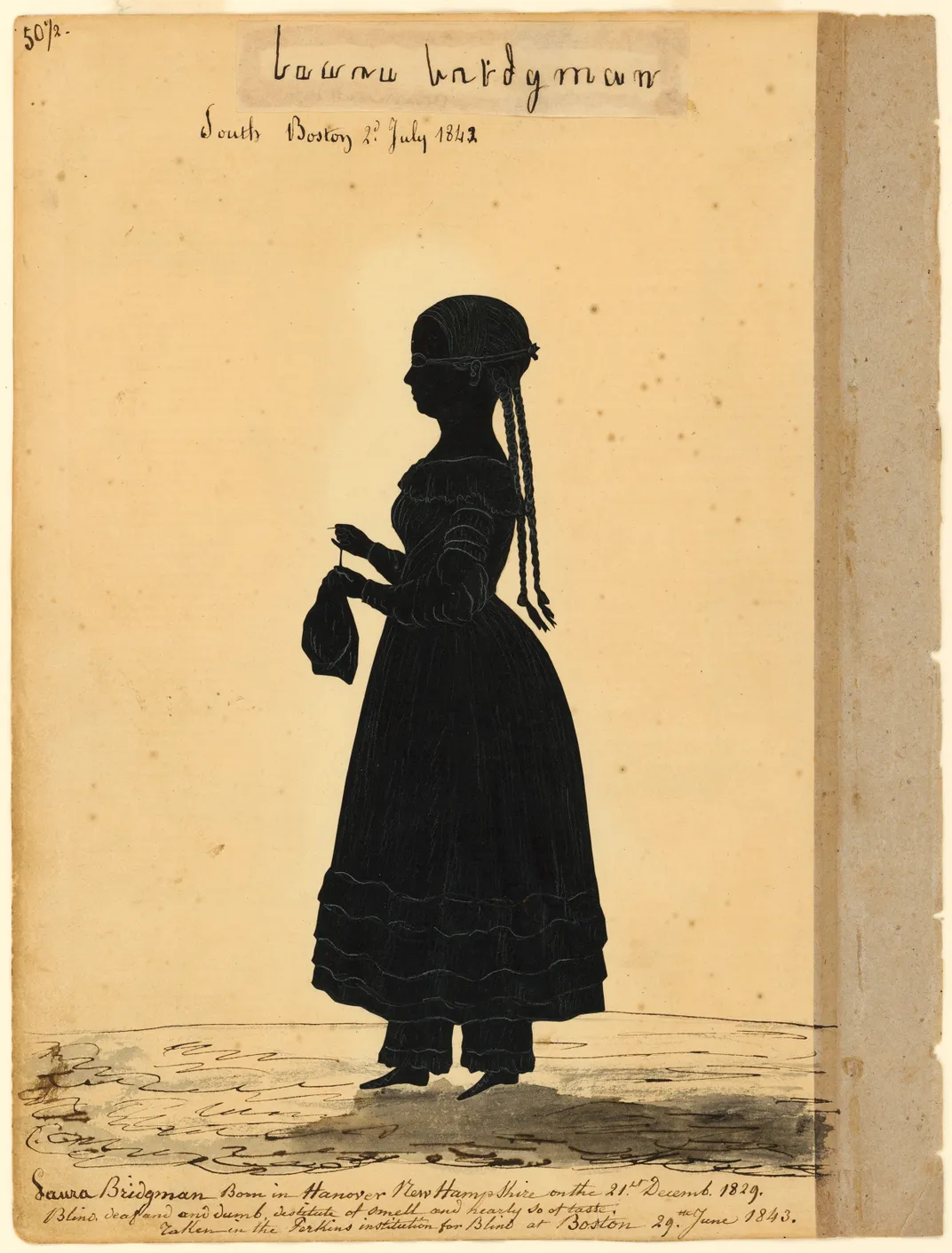

Like other recent exhibitions at the Portrait Gallery as it marks its 50th anniversary, Black Out emphasizes the “social underpinnings, drawing attention to those who have been previously blacked out from history such as the enslaved, working women, same sex couples and those with disabilities,” says Sajet.

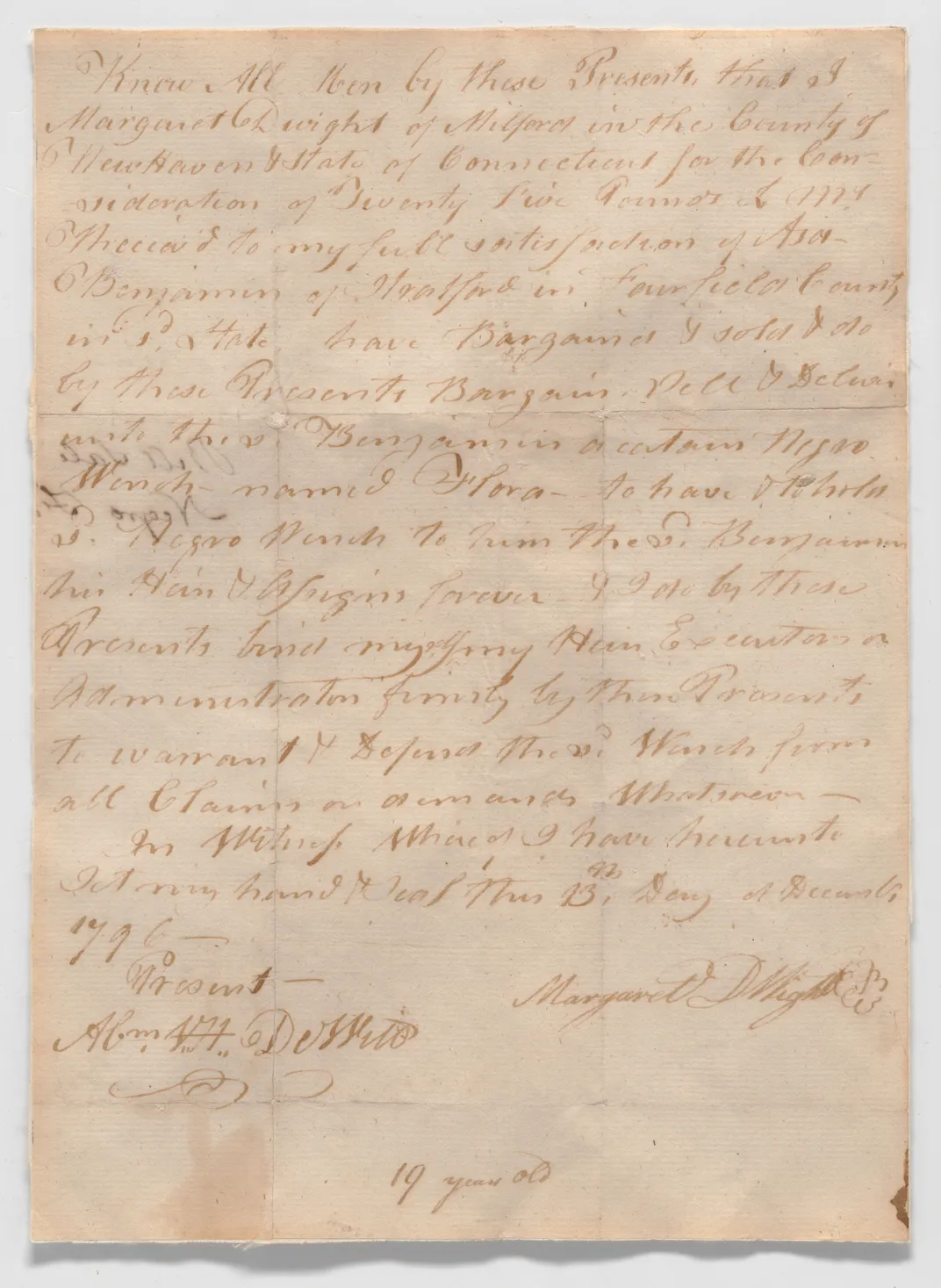

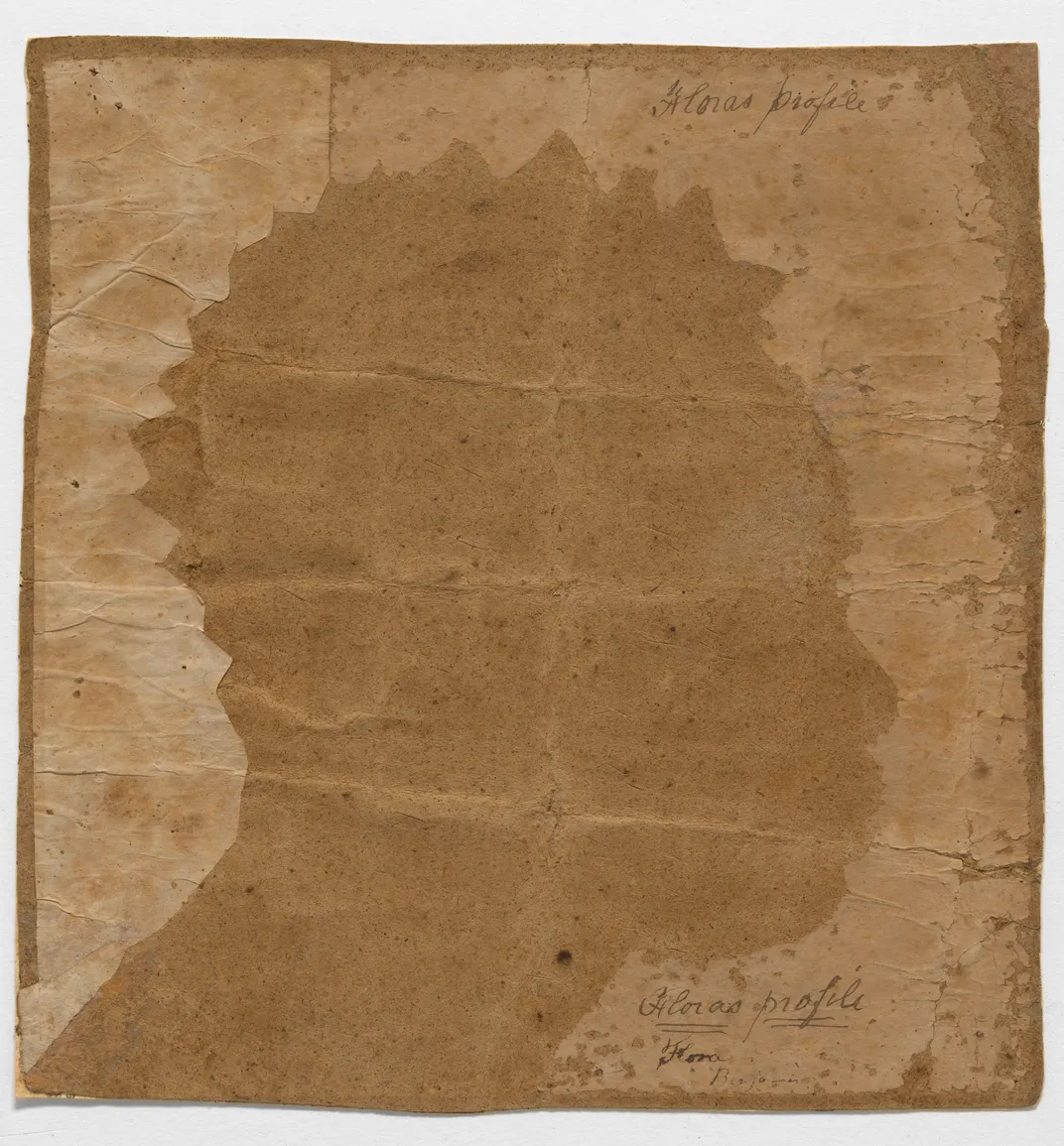

The addition of innovative contemporary work by four women artists, including one completed the night before the show’s press preview, contrast with the oldest work in the show, which dates to 1796 and is the most harrowing. It is the tremulous outline of an enslaved 19-year-old named Flora whose portrait was found alongside her original bill of sale in Connecticut for 25 pounds silver.

Lent from the Stratford Historical Society in Connecticut, Flora is “one of the very few tangible portraits that still exists of someone who was literally made a slave in America in the 18th century,” Sajet says.

“As you know, the Portrait Gallery is a place where people come to see luminaries, people come to see people who have made a significant contribution to American history and culture. But that doesn’t tell the whole American story in my view,” says Naeem. Fascinated with silhouettes as a young girl, the curator says she was delighted to find when coming to the Portrait Gallery in 2014 that the museum has “one of the most extensive collections of silhouettes in the country.”

If nothing else, the show emphasizes that it was the lowly silhouette, which nearly every family could afford to put on their wall, that democratized portraiture in America—not photography, which wasn’t invented until 1839 and didn’t become accessible for wide use until the later 19th century.

“Silhouettes have been around much longer than that,” Naeem says, going back to the 1680s when royalty offered their profile for posterity.

Interest in the cutouts grew with the rise of the pseudoscience of physiognomy that claimed that a person’s moral character could be discerned, Naeem says, “simply by the shape of your forehead, the bump on your nose or how your chin related to the rest of your face.”

“All of a sudden, this beautiful art form became annexed with this pseudoscientific field. And very quickly people wanted to know what their profile showed,” Naeem says. “The term racial profiling really gets its origins from silhouettes,” she says. “It’s the idea that people who look a certain way act a certain way, based on this pseudoscientific field of physiognomy.”

What also made silhouettes a rage, with hundreds of thousands made in America in the first decade of the 1800s, was just how inexpensive it was. “It was dirt cheap that someone from any walk of life could access,” Naeem says. “Instead of an oil on canvas portrait which would cost anywhere upwards of $100 in the early 1800s, four silhouettes cost 25 cents.”

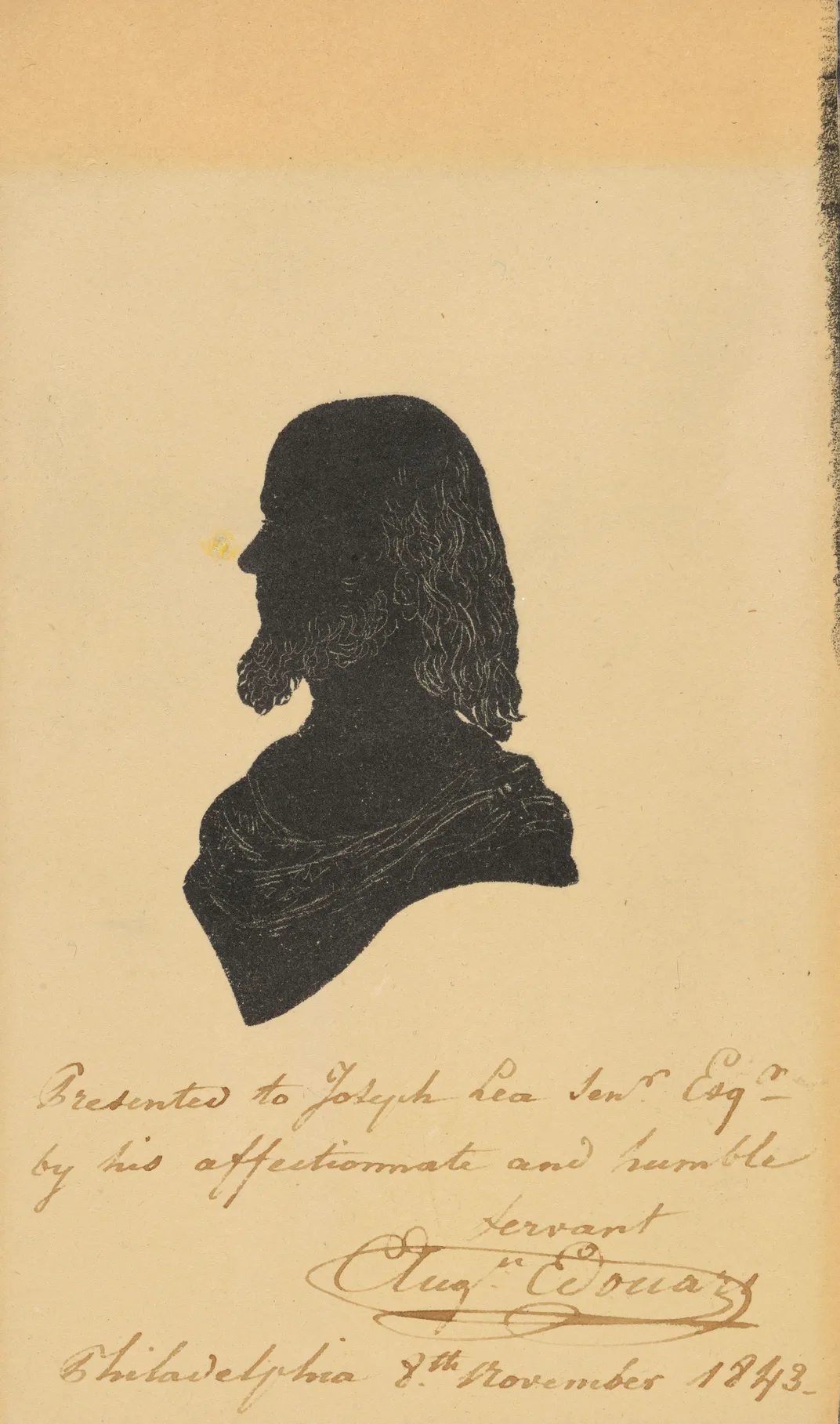

To look back at what was created now is to see, yes, ex-presidents like John Quincy Adams, depicted in a full-sized 1841 profile by Auguste Edouard, the year after Adams argued the Amistad case, but also merchants, soldiers and the enslaved. In a nation seemingly consumed in race, silhouettes erased that distinction, rendering everyone in the same black outline.

Though the heyday of silhouettes may have passed, some of its aspects continue. On social media, the word “profile” refers to what needs to be completed with a picture of oneself and a blank silhouette is a placeholder.

The use of silhouette in contemporary art has been most strongly associated with Kara Walker, whose vivid works of Civil War-era mayhem are spread along two walls, surrounding her table top Burning African Village Play Set with Big House and Lynching.

More serene is the 18-foot-tall, three-dimensional life-sized maypole with the silhouette-rendered figures of 20 children in fancy Victorian clothes by the Canadian artist Kristi Malakoff, further festooned with black ribbon and the cutouts of 50 birds flying above.

Another room brings back the interactive work of artist Camille Utterback, who was previously in the building with her Text Rain as part of the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s Watch This! exhibition three years ago. Invited to take part in another Smithsonian show in which patrons interact with a video screen and leave their own silhouette (albeit one taken by a camera in the ceiling that almost instantly becomes one of the work’s abstractions).

“Photography gives us this mistaken idea that you can hold onto a moment in a precise way,” says Utterback, a MacArthur fellow who teaches at Stamford. In her Precarious (the one receiving last minute adjustments the night before), “you’re creating an evolving system. It’s always in a state of flux.”

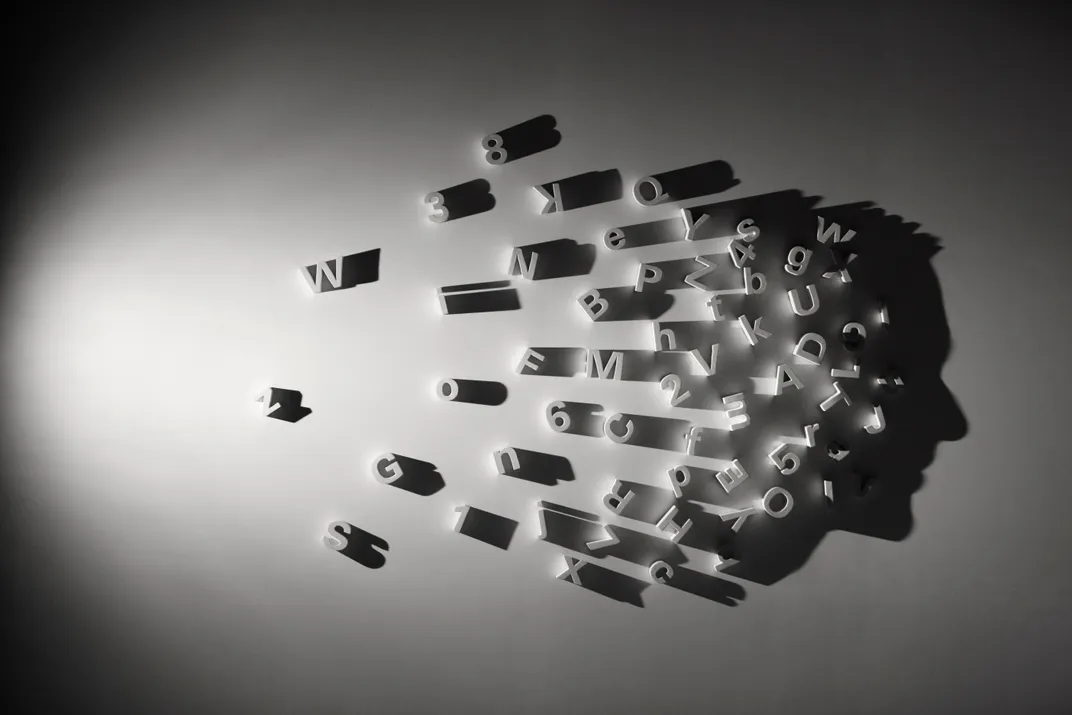

The final contemporary artist, Kumi Yamashita, a finalist in the Portrait Gallery’s 2013 Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition, is doing the opposite of silhouette cutters.

Rather than capture a shadow, she is creating them. What looks to be 16 sheets of gently ruffled colored paper on one wall, lit from the side, turns out to be shadows of specific profiles (one is of the curator Naeem).

On another wall, the eye is drawn to the jumble of letters and numbers lit from the side, only to see, eventually, the singular large human profile they create. Finally, what looks to be a slim, carved piece of plastic casts the shadow of a woman sitting on a chair.

“Many people think there’s a projection somewhere that is making that woman sit on the chair,” Naeem says, but it’s just the shadow from a single light source.

“It’s so simple people are trying to make it more complicated,” Yamashita says.

“Black Out: Silhouettes Then and Now” continues at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. through March 10, 2019.

Black Out: Silhouettes Then and Now

Primarily tracing the rise of the silhouette in the decades leading up to the Civil War, Black Out also considers the ubiquity of the genre today, particularly in contemporary art. Using silhouettes to address such themes as race, identity, and the notion of the digital self, the four featured living artists--Kara Walker, Kristi Malakoff, Kumi Yamashita and Camille Utterback―all take the silhouette to unique and fascinating new heights.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)