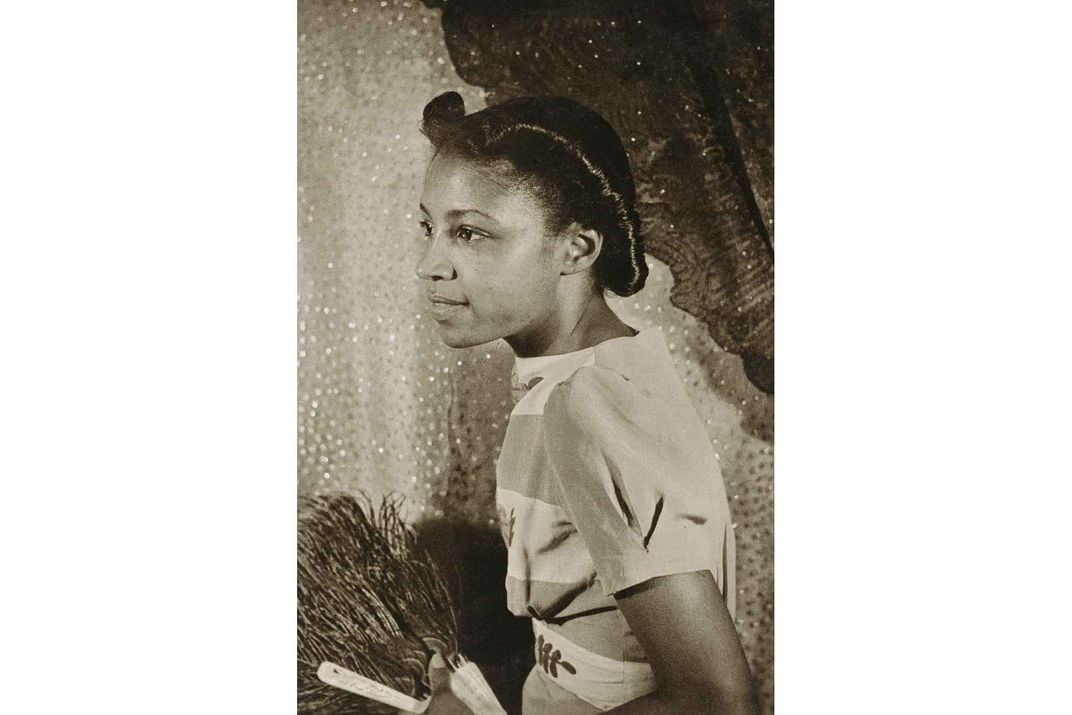

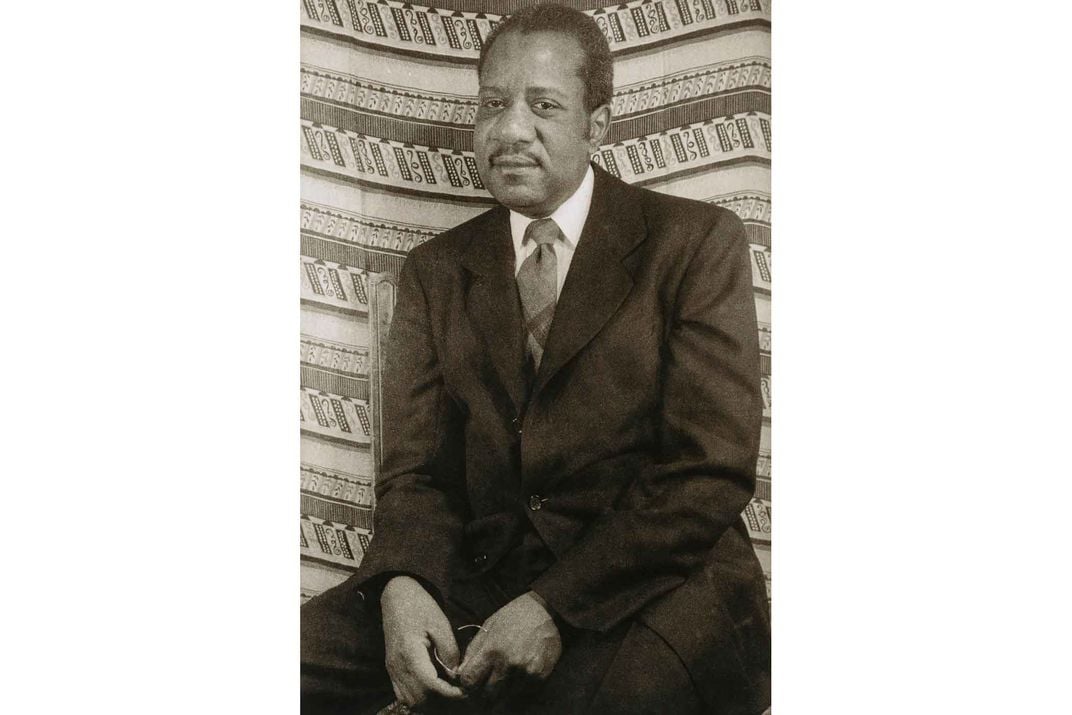

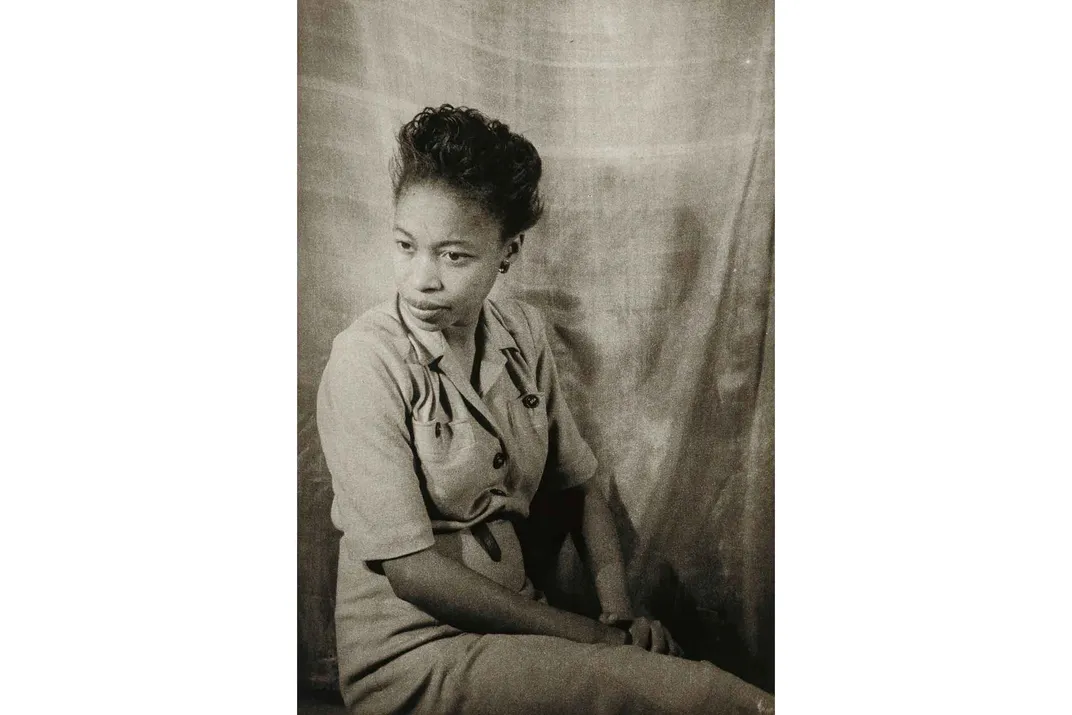

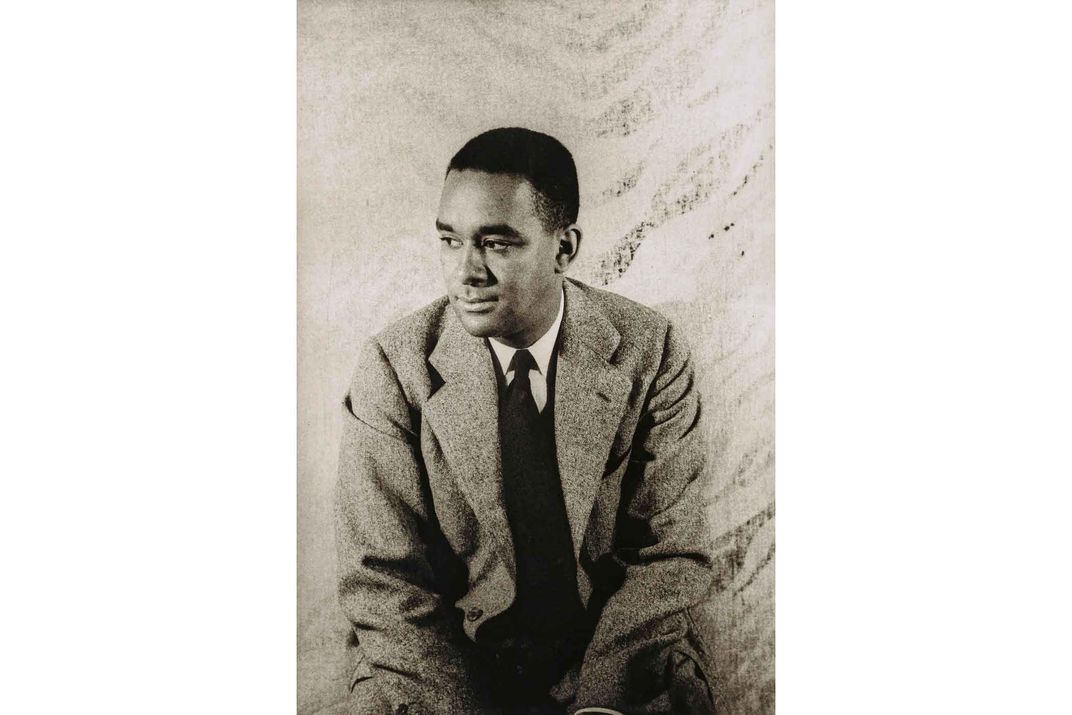

These Rarely Seen Photographs Are a Who’s Who of the Harlem Renaissance

Carl Van Vechten captured and archived images of most of the era’s great artists, musicians and thought leaders

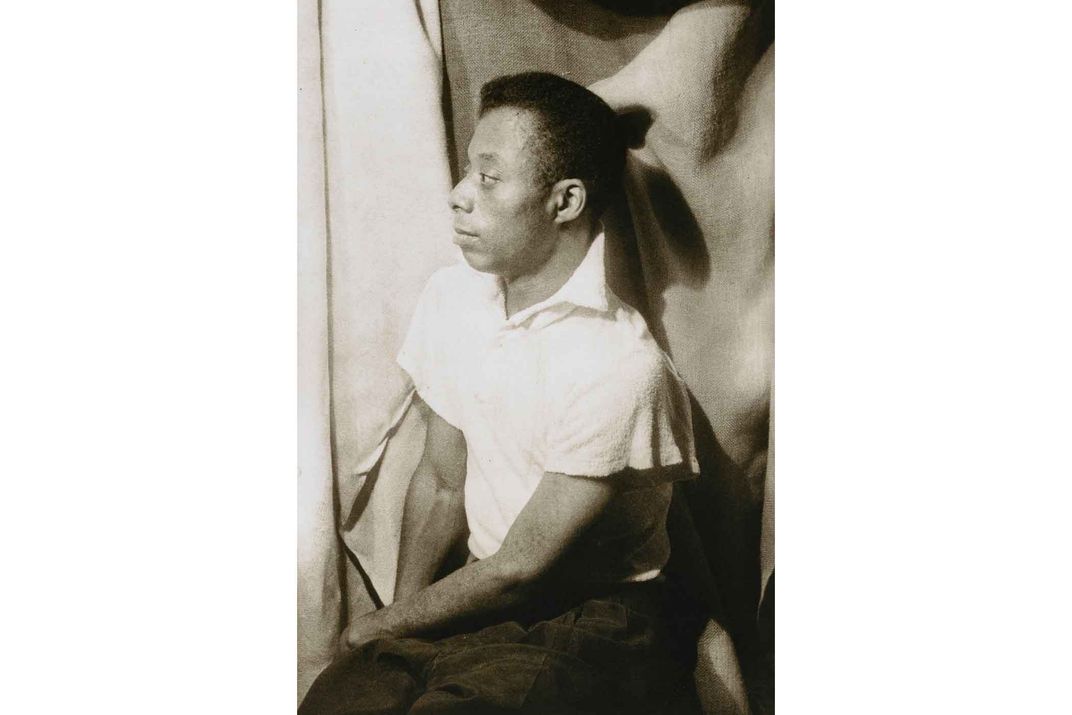

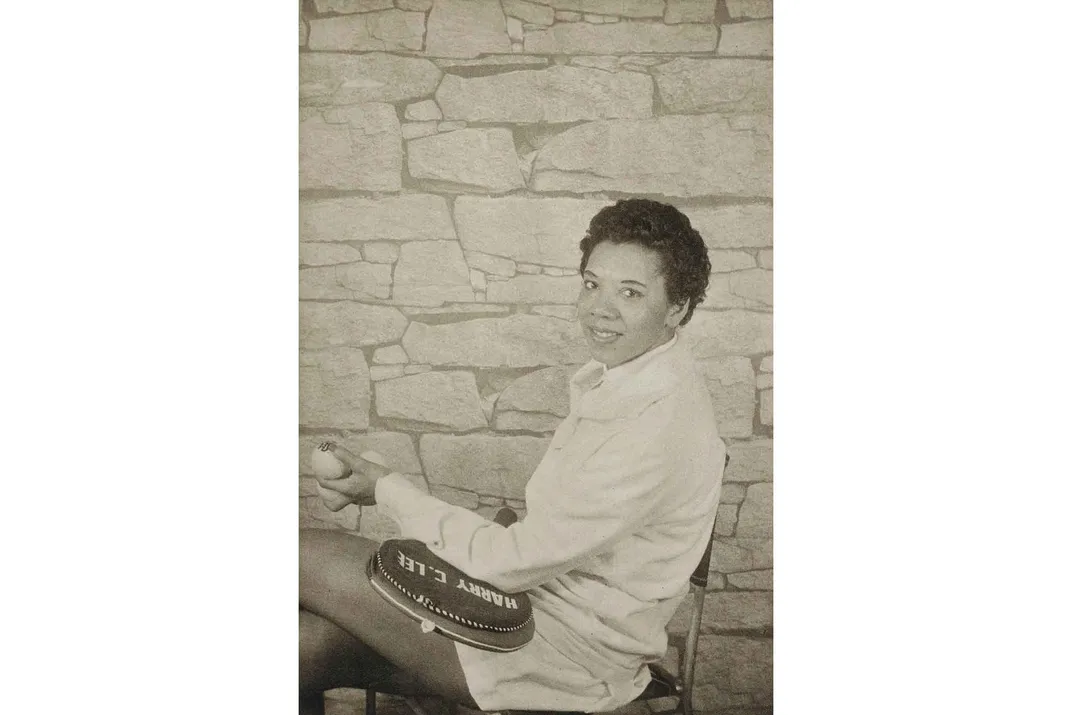

Carl Van Vechten, a familiar figure among New York City’s literary and artistic circles in the early 20th century, tried his hand as a novelist, critic and journalist, to varying results, before picking up a camera in 1932. He proved a natural photographer. But perhaps more importantly, he had built relationships (in some cases decades-long) with many of the brightest artistic lights of the era, who were happy to pose for him: James Baldwin, W.E.B. Du Bois, Ella Fitzgerald, Lena Horne and dozens of others.

Visitors to the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., have a rare opportunity to see a selection of his images—39 photographs, many of which are on view for the first time since they were acquired in 1983. The works cover a period of three decades and are some of the most striking portraits created of the groundbreaking writers, athletes, politicians, musicians of the Harlem Renaissance. Yet the man behind the camera is remembered more as a socialite and writer than a photographer. The museum’s exhibition “Heroes of Harlem: Photographs by Carl Van Vechten” aims to change that.

“Carl Van Vechten had a relatively natural style,” explains John Jacob, the museum’s curator of photography and the curator of this show. “His portraits are posed, but they’re close-up and direct, focusing on the facial and bodily expressions of his subjects. They’re formal, but they have the familiar qualities of a snapshot.”

This natural approach and the fact that Van Vechten was perceived as a polymath or dilettante—depending on your point of view, partly explain why his photography has not received more consideration.

Studio photographers such as James Van Der Zee and James Latimer Allen lived in the area and captured their community on film. Others, like Henri Cartier-Bresson, came as reporters. But Van Vechten’s motives were different than theirs.

“Van Vechten the photographer didn’t plan his portrait of Harlem. African Americans were among the social milieu in which he circulated, and their inclusion in it, at a time when exclusion was the norm, makes his project unique,” says Jacob.

While other photographers of the era saw themselves as creating art, Van Vechten saw himself creating a catalog—first of his friends and fellow artists, and after several years, focusing particularly on African-American artists and people of prominence.

“He wanted to capture the breadth of American artistic culture, including the African-American community,” says Jacob. More so than perhaps any other individual, he succeeded in this mission, leaving behind thousands of photographs, spread throughout the archives of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Yale University, the Library of Congress, and elsewhere.

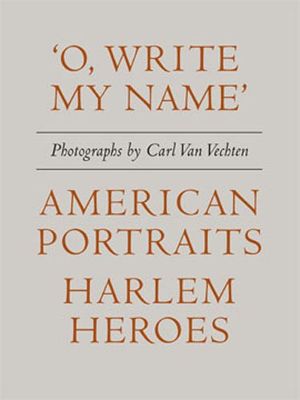

The 39 portraits included in this exhibition are delicate 35 mm nitrate negatives, restored by photographer Richard Benson for art book publisher Eakins Press Foundation. They were part of two collections Van Vechten had created: Heroes of Harlem (a portfolio of 30 portraits of African-American men) and Noble Black Women (a collection of 19 portraits of African-American women). While the Eakins Press Foundation would eventually combine both portfolios into the collection O, Write My Name: American Portraits, Harlem Heroes, the current exhibition displays the portraits from these prototype portfolios in its entirety, organized chronologically by exposure date (when the photograph was made).

“Visitors to the exhibition will see that Carl Van Vechten’s portraiture shaped an inclusive catalog of the era in which he lived and worked,” says Jacob. “That era, and the Harlem Renaissance within it, was a defining moment in our history that reverberates to this day in American culture.”

Collecting was Van Vechten’s focus.

“He tried to capture every important figure of the [Harlem Renaissance],” says Emily Bernard, professor of English and ALANA U.S. Ethnic Studies at the University of Vermont, as well as author of the 2012 Van Vechten biography Carl Van Vechten and the Harlem Renaissance. “He was interested in knowing people and collecting people and creating bonds for others—understanding how people could help each other.”

Bernard describes him as an “under-considered figure in African-American cultural history,” and attributes this in part to the fact that the photographer was white, but also to the fact that he seemed restless in his artistic pursuits, jumping from one interest to another throughout his life.

A pioneering dance and music critic, Van Vechten was also a novelist, who published a book set within the Harlem nightlife scene—and which included a startling racial epithet in its title. The novel’s depiction of African Americans and the offensive title, led it to receive wide derision (and patches of praise) among the Harlem community. Historian David Levering Lewis would famously dub it a “colossal fraud.” After this book, Van Vechten published another novel and book of essays, but then stopped writing altogether, outside of his letters.

“That’s just who he was—‘I’m done with that,’” says Bernard.

But if there is one effort that consumed Van Vechten throughout his life, it was meeting the creative figures of his era, placing himself in the center of any social circle.

Bernard is also the editor of Remember Me to Harlem (2001), a collection of letters between Van Vechten and Langston Hughes over their long and lively friendship. In addition to Hughes, Van Vechten corresponded with dozens of Harlem writers, musicians and intellectuals, saving all the letters and even making notes such as “met” next to the name. He painstakingly catalogued and preserved these letters, as well as hundreds of slides, which he donated to Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Van Vechten saw it as a badge of accomplishment to meet a prominent person—or introduce two important people to one another.

“It’s inarguable that he was a megalomaniac,” says Bernard. “He understood his place in the culture—that he was at the vortex, that he was the person who brought Gertrude Stein together with so many Harlem Renaissance figures that she would never have met.”

But he was not selfish in his sociability. Bernard sees both Van Vechten’s archive and his photography as “another arm of his work to connect people. He created the archives so people could understand the totality of the culture and what was happening in the early 20s through the 30s and 40s, so writers and readers could make a connection with this time.” She adds that, “He really wanted to educate from beyond the grave, ‘here’s what was happening in the culture.’”

Instead of seeing his photographs as reflective of his own art, he saw it as a way of preserving the world and the figures he is observing, saving them for posterity.

“His photography is unapologetically about the subject,” says Bernard. “He had a really precise sense that those photos were going to be archived. That was part of the artistic process for him.”

To help with this educational mission, he would even introduce props into his work, such as flowers surrounding Altonell Hines or a guitar for Josh White; and used the setting or backdrop to help convey something about the person, such a boxing ring for Joe Louis or landscape backdrop for Bessie Smith.

Collectively, these photographs try to make sense of the exciting and fast-changing culture of the time and “capture the essence of his subjects,” as Bernard puts it. “When you read about them you sense there is a whole matrix, not just individual subjects, but a whole world—and Van Vechten is the insider to that world; there was no one who was more important.”

She emphasizes that looking at these images today, a viewer will see how well Van Vechten knew his subjects, and that he wants to share this knowledge.

“He really was concerned about the viewer—he did this for you,” says Bernard. “He wanted the audience to know them as he knew them.”

"Harlem Heroes: Photographs by Carl Van Vechten" is on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C. through March 29, 2017.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alex_Palmer_lowres.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/95/d6/95d665fc-8c42-4d46-b035-d52bcf6f927f/smith_bweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/48/ab/48abf625-4a66-4860-9c8e-fd0458e6cbb8/mcclendonweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/66/92/66924822-0ae8-403d-a349-596493c3f608/petersonweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a3/de/a3dee771-6ad8-46f4-97a7-884fffe46165/priceweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/33/f6/33f6207a-0218-44c1-be9c-be6a54c175b3/pippinweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/54/d4/54d46f4a-a72a-41ce-9889-8478bb0b9c6f/robeson_eweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ce/b5/ceb538f0-d976-46db-856a-91966607bcf1/robeson_pweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f5/15/f51529ab-a1bf-4e2f-ac8b-c63cc2518f48/robinsonweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e0/5a/e05ad8b0-c48f-42dd-be4b-f735a11ada74/smith_aweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2f/31/2f31be73-9cec-4f85-8921-185579f83b6b/louisweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/64/bd/64bdaedc-1345-4118-98d0-f63c56734a41/whiteweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6f/b4/6fb4d782-62fb-466e-8d14-6d06cd1edbc9/washingtonweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/86/21/8621944e-2630-4153-8117-c1209a818580/watersweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/37/5f/375fa62f-5242-4d91-b81c-ef9bcc6d5e35/bubblesweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d0/b7/d0b75bb2-71d8-41db-b209-c1ead286fb96/beardenweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6e/49/6e49a7d3-253d-4c9a-b8f4-2c9dc360266d/davisweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/df/58/df5895f2-e42e-46ab-8403-359163135e26/duboisweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c9/bc/c9bcf7d2-fae6-4401-8009-a14aa2eeb5c8/dunhamweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/47/23/4723fd71-1873-446a-a1c7-5078d25ec465/buncheweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e0/23/e023327d-599b-4c55-abe9-575ec015d201/elzyweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8a/7d/8a7d0204-a3bc-4ac6-b5de-0cb3b8e2232e/hinesweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9e/84/9e8457c4-a69d-4c0a-8e8d-202e343b1f3a/bethuneweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bc/9a/bc9a7634-0ccb-4ba9-b1d1-8b06f840e1ca/holtweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/65/82/65825ac9-f7e0-4162-9376-bf29b45cfa05/horneweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/25/91/25917cd6-7afa-4a1e-8d83-e32100b33e61/hurstonweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6f/3d/6f3d3f9a-bf44-42c4-be4c-690b19a44e43/jacksonweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3d/c3/3dc3ccdc-54de-4f38-b829-07077918c1e6/hughesweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cc/73/cc739f32-d264-4dd4-a1a9-a91eb9d0f8e1/johnson_cweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2e/92/2e92793c-cca4-4182-a985-3a729fad88bc/lawrenceweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ff/d2/ffd2881e-4c16-47de-b95e-855b643a99c8/johnson_jweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alex_Palmer_lowres.jpg)