Ray Charles’ Fusion of Gospel and Blues Changed the Face of American Popular Music

A visionary virtuoso, Charles made brilliance look easy

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a8/6e/a86ef313-01d1-4038-a7de-fcc0fda9d6c0/raycharlesraybans200531437web.jpg)

Ray Charles, who died at age 73 on June 10, 2004, lives on in America’s collective inner ear. So much so that it’s a challenge to think of anyone else who ever performed such songs as “Georgia On My Mind,” “What’d I Say” and “You Don’t Know Me.”

And if anyone other than Charles ever sang a more heartfelt, heart-stirring version of “America the Beautiful,” I haven’t heard it. Perhaps there is no more telling measure of the man’s musical genius than that in a business where the bond between audiences and performers is as much visual as vocal, we listened to Charles and watched him during his long career without ever once making eye contact. In this singer’s case, the window to the soul was the ear, not the eyes.

But who could take their eyes off Ray?

He had the nonchalance of transcendent talent—he could make brilliance look easy. “Music to me is just like breathing,” Charles once told an interviewer. “It’s part of me.” And when we watched him sway to the rhythm of his songs like some living metronome, we focused on his jubilant smile and ever-present sunglasses.

Those lenses were both fact and metaphor, reflecting his audiences as his songs reflected the emotions of fans who spanned generations.

In September 2004, John Edward Hasse, curator of American music at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, and Melinda Machado, the museum’s director of public affairs, visited the Los Angeles studio built for Charles in 1962 where the singer recorded his songbook of unforgettable hits. The pair hoped to acquire an object symbolizing the performer who orbits in the galaxy of Bing Crosby, Judy Garland, Frank Sinatra and Ella Fitzgerald.

“We had decided,” Machado says, “that if there was only one thing we could get, it had to be a pair of Ray’s sunglasses.”

Joe Adams, an actor who was Charles’ longtime manager and the designer of many of his performance outfits, arranged the visit. “As we walked in,” Machado recalls, “I felt that Ray Charles was very present.”

Hasse, the founder of national Jazz Appreciation Month and an accomplished musician himself, got a chance to play a series of blues improvisations on one of the studio pianos. “I was inspired just to be there,” he says.

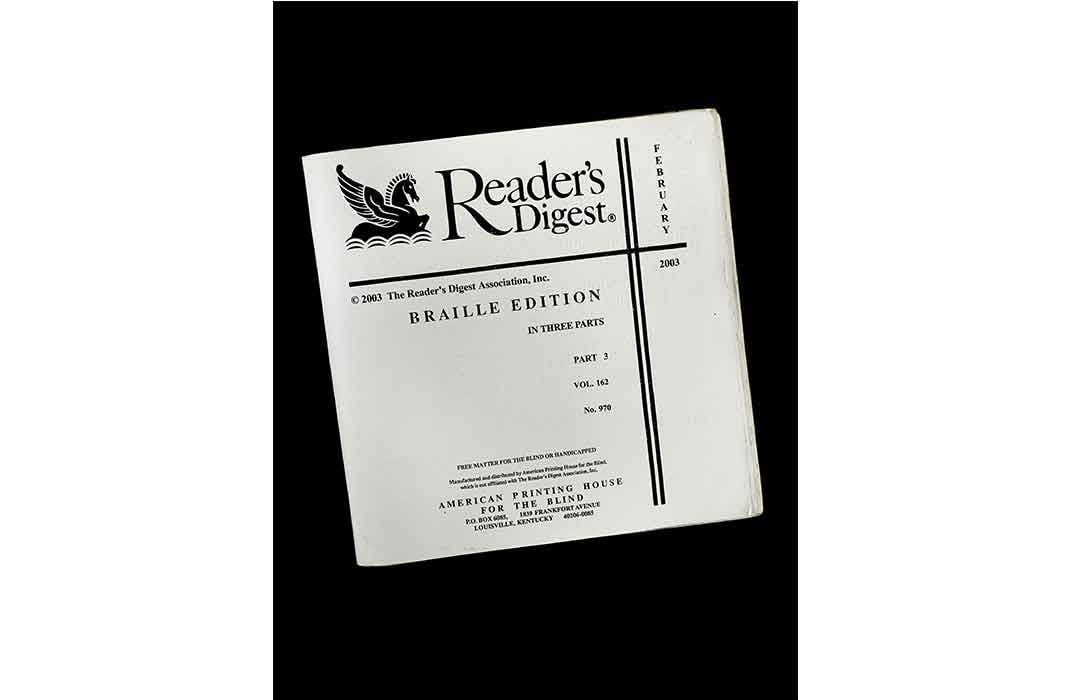

The custom-made jackets and tuxedos Charles wore for concerts and television appearances hung in a large, open closet. His collection of sunglasses was in a cabinet against one of the walls. “Ray liked variety,” Adams said, “so he wore different styles.” But to Hasse and Machado, a particular pair, with wide earpieces, seemed the most familiar and characteristic. . . .Ray’s Ray-Bans.

Adams donated the glasses—as well as three stage costumes, a Yamaha KX 88 keyboard marked in Braille, a chess set for the blind and two concert programs—in a ceremony at the museum on September 21, 2006.

In a 2005-2006 exhibition entitled “Ray Charles: The Genius,” a mannequin wore a gold-sequined dinner jacket and black trousers. Where the mannequin’s head should have been, the famous shades floated in midair at eye level. The exhibition, Adams said brought back a lot of good memories. “We covered a lot of ground together.”

To which those of us who still see ourselves reflected in the glasses of one of our brightest stars might simply add: “Amen.”

On February 26, 2016, at 9 p.m., PBS stations nationwide will premiere “Smithsonian Salutes Ray Charles: In Performance at the White House.” Check local listings. On February 19, the popular exhibition “Ray Charles: The Genius,” returns to the National Museum of American History.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)