Ray Charles Returns to the White House

The blind king of soul once sat down with Richard Nixon, now his music will be performed by a host of musicians for Barack Obama

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/57/a6/57a6bd63-c68f-46b0-8879-271dbef8ed5d/na013174web.jpg)

Ray Charles took his seat in the Oval Office. Richard Nixon, sitting beside him, instinctively tried to look him in the eyes. Charles did not look back. He wore chunky black sunglasses and an eye-catching paisley tie. The hair around his temples had just barely started to turn gray, lending a new touch of dignity to the musician. The President of the United States began a conversation with the blind king of soul music.

“I lived next door to a gentleman, who was a pianist,” Charles said to Nixon as the now-infamous hidden tape recorder slowly turned, “and I loved to hear him play when I was three and four years old.” He continued, telling Nixon about growing up in poverty as the son of a laundress in rural Florida and discovering a love for the piano before losing his sight at the age of seven.

The pair may not have been entirely an odd couple. They were both piano players, though of widely different talent. A few years earlier, Nixon had personally played "Happy Birthday" for Duke Ellington on a grand piano in the East Room of the White House. But Ellington's big-band jazz had become respectable in a way that soul music, for which Ray Charles was best known, had not.

Most black music, including blues, soul and certainly rock ‘n’ roll were not art forms that museums, politicians or cultural attachés took seriously. Forty-four years later, Ray Charles is gone but his music is finally coming to the White House. As part of an on-going concert series PBS has partnered with the Grammy Museum, TV One and the Smithsonian Institution, among others, to present “Smithsonian Salutes Ray Charles: In Performance at the White House.” On February 26, the show—featuring a host of today’s recording artists reinterpreting Charles’ music and big-band arrangements—will air on PBS stations nationwide.

For most of his professional life, Charles toured relentlessly. Often traveling nine months out of each year, he managed something resembling a small army of musicians, singers and support staff that flew around the U.S. and abroad. “It does this country a lot of good for you to do that,” Nixon said to Charles in the Oval Office. “The people [in Russia and in Czechoslovakia], the only way they can express themselves is to cheer for an artist.”

But while Ray Charles personally took African American music around the world to new audiences, he was frustrated by the lack of institutional support from his own government, including official State Department goodwill tours. “As a rule, though, the kind of people who work for the State Department probably feel that the blues is beneath them,” Charles said in a 1970 interview with Playboy magazine. “They wouldn't be caught dead listening to Little Milton or Howling Wolf. They don't even know these cats exist, so they couldn't be expected to ask them to go on tours. To the people in Washington, all this music—maybe with the exception of traditional jazz players like Louis Armstrong—is somehow in bad taste. But you know, two-thirds of the world is playing it and dancing to it, so I guess there's a hell of a lot of people with bad judgment, wouldn't you say?”

Popular black music has finally found a permanent home in Washington, D.C. After over a decade of planning and collecting, the National Museum of African American History and Culture is expected to open its doors to the public September 24, 2016. It features a large collection devoted to music, which includes one of Charles’ classic single-button jackets (The National Museum of American History has a pair of his signature black sunglasses).

The jacket is blue with a tangle of silver flowers embroidered into it. It is crafted of tactile fabric with a pattern that could be felt under the fingertips and recognized by a blind man, who believed in his own sense of style. He wore a simple light gray summer suit to meet with Nixon. The wide paisley tie looked as though it could have been made to match the flamboyant jacket in the new museum's collections.

Dwandalyn Reece is the curator of Music and Performing Arts at the African American History Museum (and is one of the organizers of the upcoming concert at the White House). For years, she has been curating a collection without a physical museum to display it in. “It's kind of scary,” Reece says. “It's the opportunity to see all your hard work be put before the public for them to hopefully enjoy. It’s also humbling. That this museum means so much to so many people, to actually be a part of it is really a humbling experience. They're going to be touched by things that I may be taking for granted at this point.”

The Music and Performing Arts collection includes not only items from the histories of Jazz and early soul, but also material from current black artists. “We have a bass and an amplifier from Fishbone,” Reece says. “We have stuff from Bad Brains, we try to be contemporary in all things. We've got some Public Enemy, we've got some stuff from J Dilla. Hip-hop artists, punk artists. We collect in all areas of African American music-making. . . we're looking at people in classical, we're looking at country. Even in rock and in punk rock.”

One of the things that made Ray Charles noteworthy enough to merit a White House invitation was his ability to work across genres. While he is typically remembered as a soul singer and piano player, he also made several successful albums of country music covers. Many fans were unhappy with that direction until they actually heard him playing the music. Working in jazz, blues, country and rock ‘n’ roll, he excelled at selling black music to white audiences and white music to black audiences during the 1950's and 60s through the Civil Rights Movement.

“If I go out into a march, first of all, I can’t see, number one,” Charles told National Public Radio in 1984. “So somebody throws something at me, I can’t even duck, you know, in time.” A picket line in KKK country was no place for a blind man. But he supported the protest movement with money for lawyers and bail. His tour stops always boycotted segregated venues.

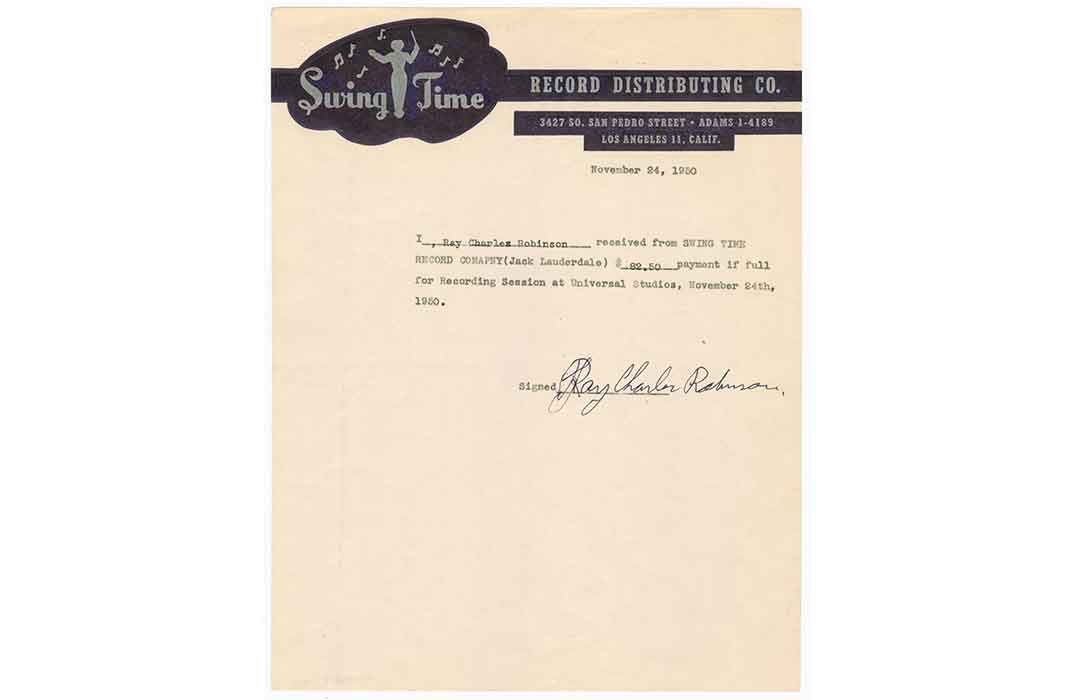

With his own record label, a Los Angeles recording studio, control over his master tapes, two airplanes and a staff of eighty-some people, he was the Jay-Z of his day; A powerful figure in music and in business who blossomed out of poverty to eventually do exactly as he pleased. “What makes Ray Charles unique was that he was in a position to be his own man in the deals he was able to make and in the economic power he had,” says Reece. “He was a symbol of success but also someone who had his own sense of agency and operated in that way, just like any other person would want to do.”

As Charles stood and prepared to leave the Oval Office, Nixon handed him the gift of a set of cufflinks bearing the seal of the President and complimented him on the tailoring of his shirt. “I like his style,” the President remarked in his distinctive growl.

Twelve years after his death, Ray Charles is finally getting his due from the government with which he had a complicated relationship. Under its laws he was banished to the back of the bus that carried him from his native Florida to Seattle, where he would get his first big break. The same government arrested him on the tarmac at Logan International for bringing heroin into the U.S. from Canada. Now his glasses and jacket are about to be displayed at the Smithsonian and a concert of his signature songs is being prepared for the East Wing of the White House—under America's first black President.

On February 26, 2016 at 9 p.m., nationwide PBS stations will premiere "Smithsonian Salutes Ray Charles: In Performance at the White House." Check local listings.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JacksonLanders.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JacksonLanders.jpg)