Even though three nations are sending exploratory orbiters and landers to Mars this month, it’s far from the first time skywatchers have been mesmerized by a mission to our nearest planet. In 1997, the world watched with wonder as Pathfinder bounced its way to a landing and then deployed Sojourner, the first wheeled vehicle to traverse another planet.

Photos sent back by the rover, operated by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in conjunction with NASA, quickly captured the nation’s attention. A nascent World Wide Web just couldn’t keep up with the demand. In one day, the Pathfinder websites set a record with 47 million hits—still an impressive number even by today’s standards.

“Pathfinder broke the internet,” recalls Jim Zimbelman, geologist emeritus at the Smithsonian’s Center for Earth and Planetary Studies at the National Air and Space Museum. “There were so many requests for photo downloads that the JPL was not ready to deal with that.”

The mission took the world by storm in 1997, but interest began to build the year before when scientists announced that a meteorite found in Antarctica contained signs of possible ancient life on Mars. NASA, which was preparing Pathfinder for a later launch, pushed forward the mission and took off for the Red Planet in December 1996.

Earthlings were riveted when the spacecraft touched down on July 4, 1997. NASA had not been to Mars since two Viking landings in 1976. While exciting at the time, those landers were static and stayed in one place. Pathfinder carried with it a new engineering feat—a moving rover named Sojourner.

“It was such a novel mission,” Zimbelman says. “I was at a scientific meeting about a year before where they first explained what Pathfinder was going to do and I remember thinking, ‘This is crazy!’”

That mission was unusual, to say the least. At the time, NASA and JPL were concerned that Pathfinder and Sojourner would not survive descent through the Martian atmosphere, which is about 100 times thinner than Earth’s, using parachutes. Instead, they came up with a different solution: Envelope the spacecraft and rover with airbags and let them bounce their way on to the planet’s surface.

“That was the first use of this type of landing, the airbag-assisted landing,” says Matt Shindell, space history curator at the museum. “They used it on later missions, but in 1997, it was the first time they had attempted that particular engineering solution. Landing on Mars is difficult because of the thin atmosphere. We had been there before in 1976 with the Viking landers. Descent engines slowed them down. But there was a concern with this type of landing that the heat of the engines could ‘cook’ the surface and prevent the collection of clean samples for analysis. So they came up with the idea of airbags to crash-land in a safe way.”

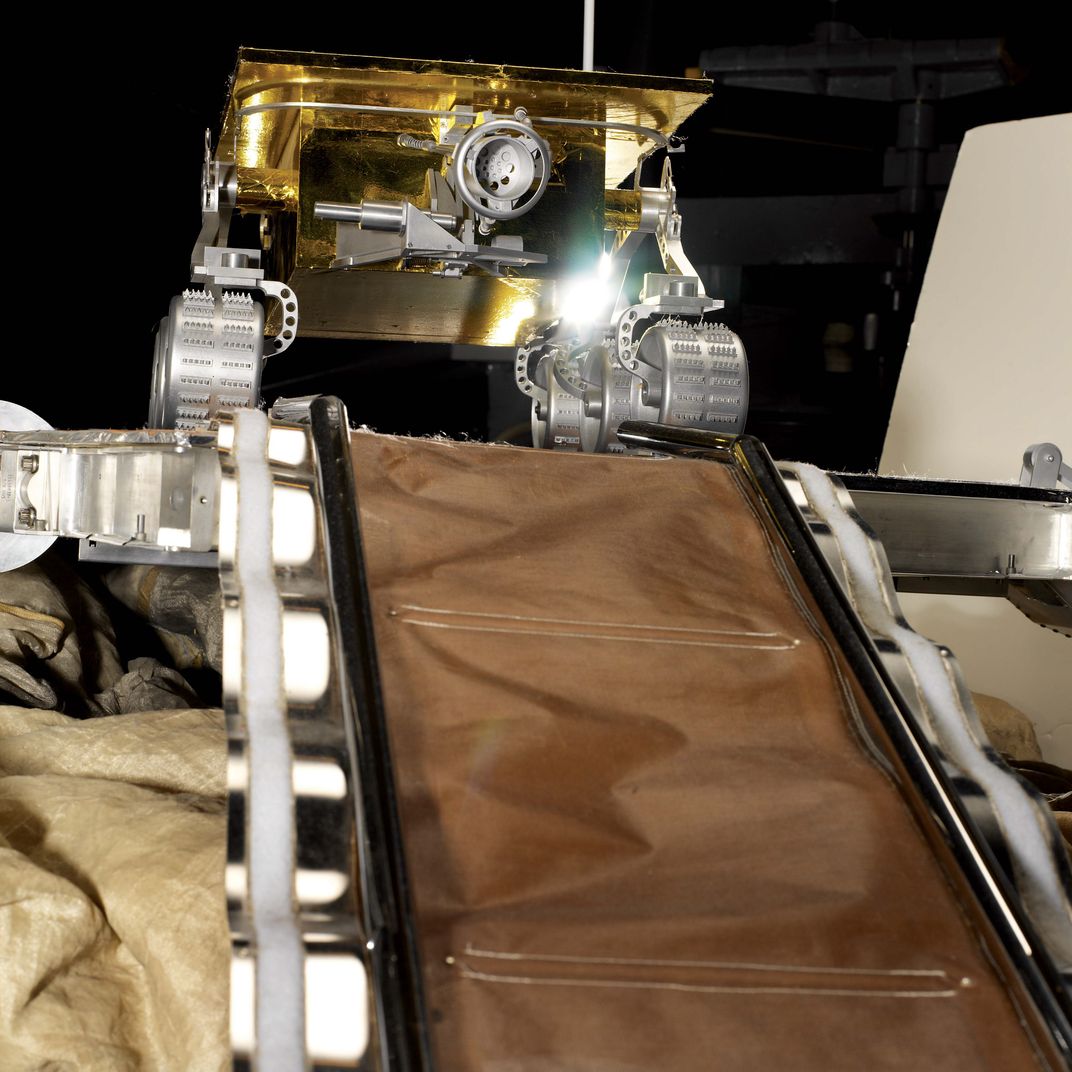

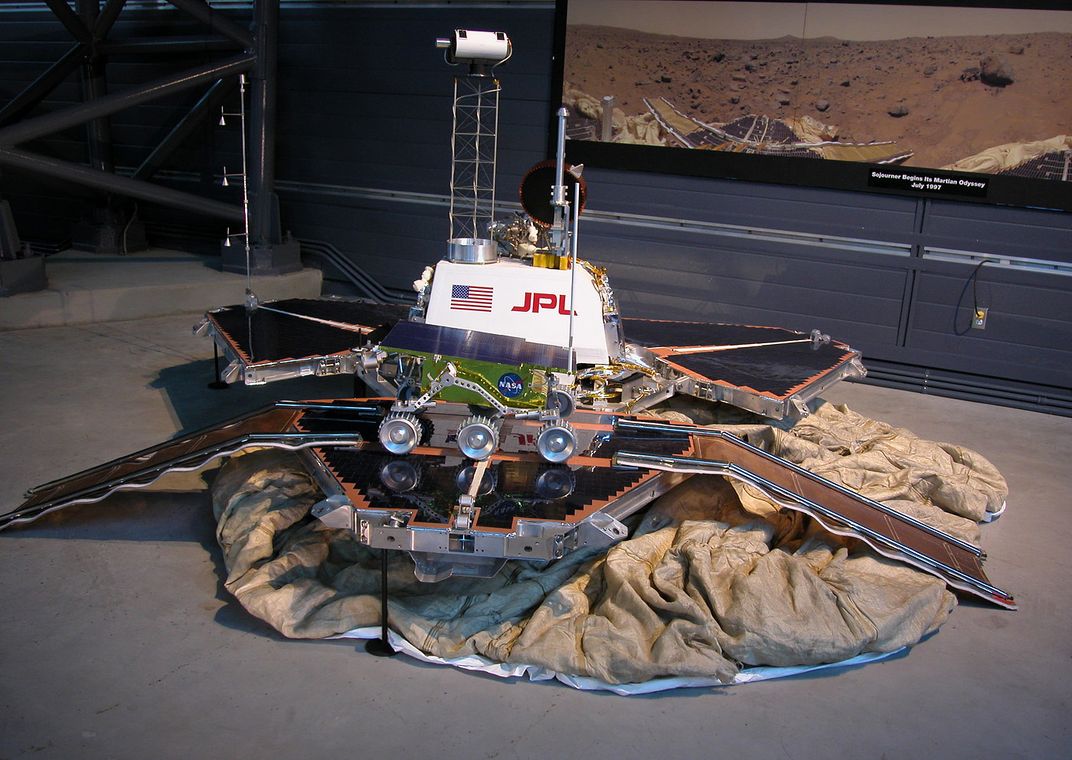

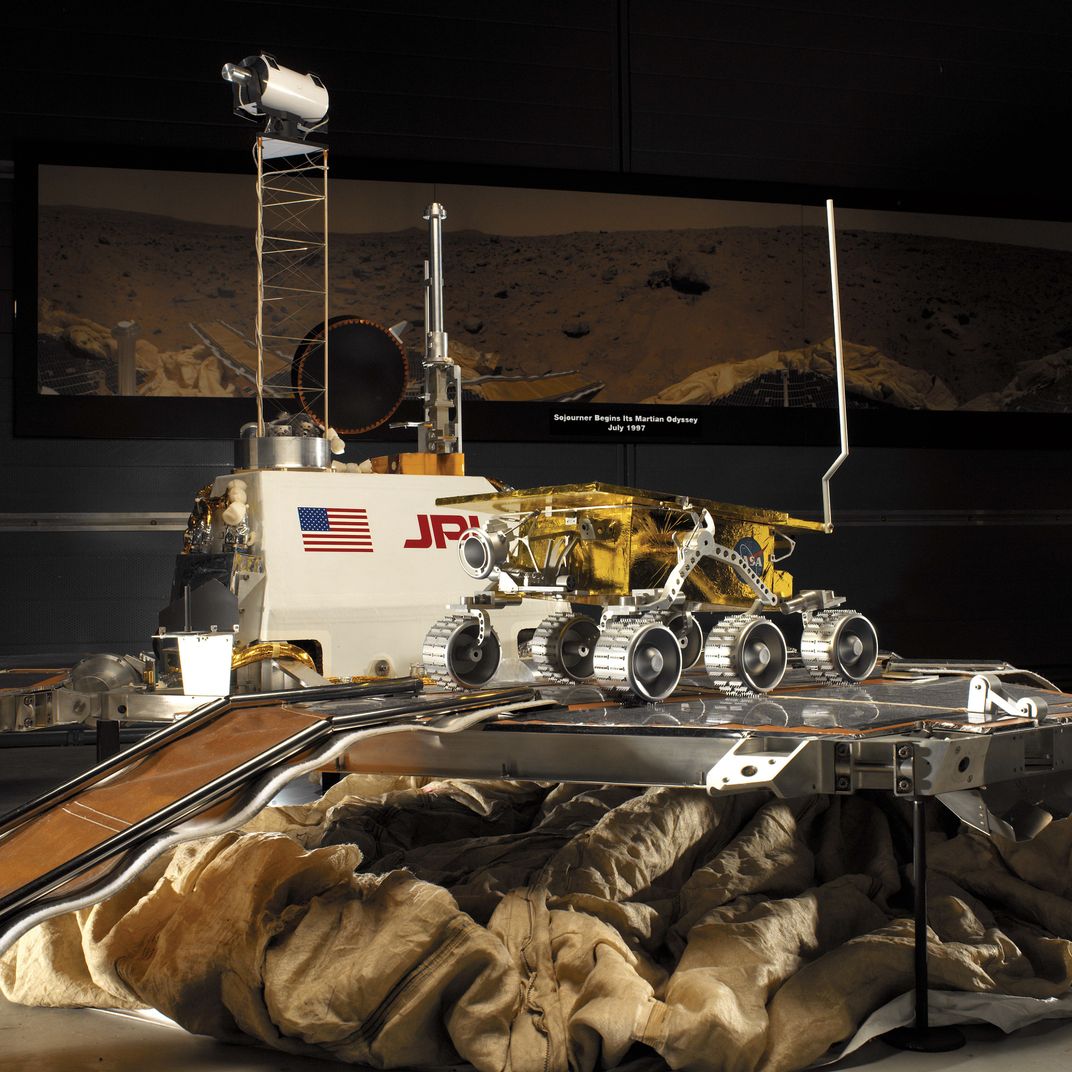

The Pathfinder mission used a combination of four descent methods. First, a heat shield was used as it entered the Mars atmosphere, then parachutes, followed by rockets before the airbags surrounded the lander. Once Pathfinder bounced to a stop, the cushioned covering deflated and Sojourner rolled out to explore the other-worldly surface like no mission before it.

On display at the Air and Space Museum’s Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia, is the prototype for Pathfinder. A model of Sojourner sits on top of the lander. These artifacts offer an exciting look back at the then-innovative technology that enabled NASA to collect 1.2 gigabytes of data and take 10,000 photos of the Martian surface.

“Sojourner could drive directly up to rocks so it could get close-up views, spectrometer readings and really study them in situ,” Shindell says. “It did what geologists typically do, which is to study a field site by looking at the rocks, where they are placed, what they are made of and how they relate to each other.”

The rover sent back a treasure trove of information that ignited interest around the globe. The stunning photos of Martian rocks—taken with two color and one black-and-white camera—were hugely popular and people everywhere wanted to see them. NASA and JPL had set up 20 “sister” websites for the expected public demand and curiosity, but they were not enough.

The 47 million views recorded on July 8 were more than double the hits received only the year before on any one day during the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta. In addition, the Pathfinder websites recorded 565 million hits worldwide between July 1 and August 4, 1997.

Zimbelman found himself awash in the public’s passion for Pathfinder. As a Smithsonian expert, he spoke to several congressmen about the Mars mission and appeared on television with a North Dakota senator talking about its importance to the space program. Everyone was captivated by what was happening 121 million miles away.

“Pathfinder was a big deal to scientists, but it was an even bigger deal to the American public,” he says. “Here was something that was so wacky but it worked, and everybody just loved it.”

Designed to last for about a month, the solar-powered rover made it to 70 Martian sols, or 85 Earth days. It sent its last transmission back to Earth on September 27, 1997, capturing far more data on the atmosphere, weather and geology of Mars than scientists expected.

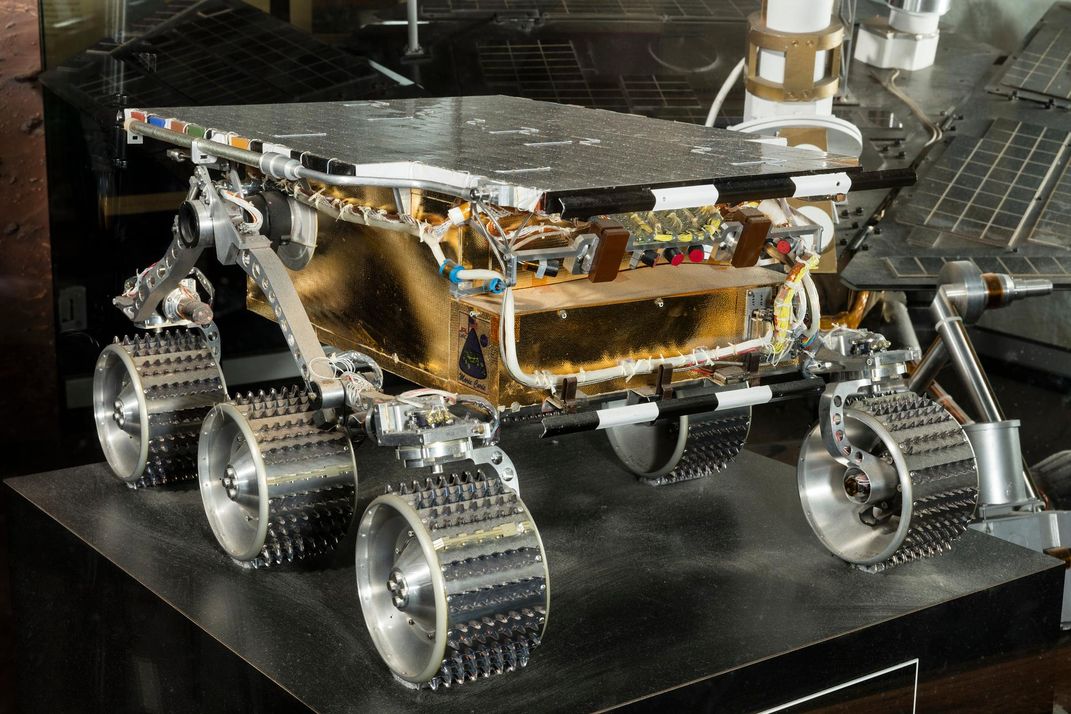

Two rovers were prepared for that 1997 mission to Mars. The unit that landed on the Red Planet was named for the abolitionist and women’s rights activist Sojourner Truth. The second one, named for scientist Marie Curie, was the backup and was to be used if something happened to the main rover prior to launch.

“The Marie Curie rover was a fully operational unit,” Shindell says. “I’m not sure at what point it was decided which was going to fly and which one would stay home, but it was ready to replace the main unit at a moment’s notice.”

Presented to the National Air and Space Museum by JPL in 2015, the Marie Curie rover will be redeployed in the redesigned "Exploring the Planets" gallery when the museum, currently under a massive renovation, reopens in 2024.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/13/48/13489dd3-b6da-48d9-886f-7b3c0d8d3668/longform_mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/60/69/606957ec-02c1-4ef6-bbe2-b7a600dc6234/social-media-dimensions.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/dave.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/dave.png)