Before Reefer Madness, High Times and 4/20, There Was the Marijuana Revenue Stamp

Originally designed in the 1930s to restrict access to the drug, these stamps draw a curious crowd to the Postal Museum

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b4/4d/b44d23f7-7a88-4b65-8c60-992ade41fdfc/clairerosen_taxstamps_img_7346-wr.jpg)

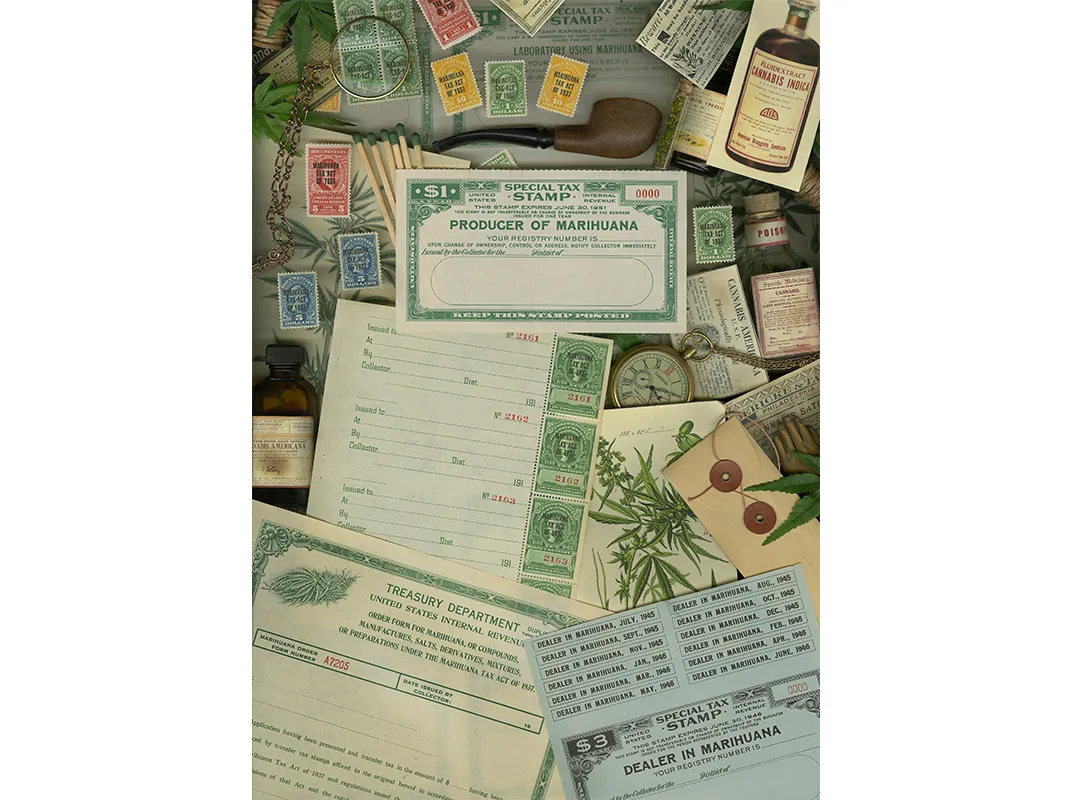

When the United States government issued its official Marijuana Revenue Stamps in 1937, the year after the exploitative film Reefer Madness declared weed a national scourge, it didn’t engrave a special issue tax stamp with a distinctive cannabis leaf, as Kansas and Oklahoma eventually did.

Nor did it make dire warnings out of its stamps with a skull and bones, as Nebraska did, or depict a grim reaper pointing the path to drugs, death and taxes as Texas did.

Instead, it merely printed over existing official documentary stamps picturing long forgotten treasury secretaries with the words "Marihuana Tax Act of 1937" (they were also using the prevailing spelling of the era).

Despite the lack of elaborate psychedelic design or head shop curlicues indicating smoke, the revenue stamps, along with accompanying official “Marijuana Order Forms,” tax stamp books and ephemera, have become items of, shall we say, high interest at the Smithsonian’s National Postal Museum in Washington, D.C.

That may be particularly true on April 20—the unofficial national high holiday for weed as designated by 4/20, once the designated moment of the day to light up as determined by a handful of stoners at a California high school and that has since become its own code for pot.

The National Postal Museum's rare federal Marijuana Revenue Stamps, located in the National Stamp Salon's vertical pullout drawer no. 197 of the William H. Gross Stamp Gallery, were originally created to restrict and regulate the drug's use, says Daniel Piazza, chief curator of philately at the museum. They came to the Smithsonian Institution in the 1970s from the U.S. Treasury Department after a change in the law made these types of revenue stamps obsolete.

Unlike other things that used tax stamps—from tobacco and alcohol to matches and margarine—the stamps for marijuana weren’t intended to raise revenue, Piazza says, but rather to restrict the use of the drug. “It was more about controlling access, really.”

The Harrison Narcotics Act of 1914 had been the first federal measure to tax and regulate controlled substances like opiates and cocaine. Marijuana was to have been included in the act, though the pharmaceutical industry opposed it, saying the substance was not habit-forming.

The decision of the federal government to tax marijuana in 1937 came after Harry Anslinger, who was commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics for more than 30 years, testified in a Congressional hearing that marijuana “produces in it users insanity, criminality and death.”

“The idea of the tax stamps was that it was a method of limiting access and controlling who could have access to marijuana,” Piazza says. “So there was actually a whole series of steps that took place before you ever purchased the stamp.”

Until 2005, when the National Postal Museum sold duplicates from the collections, there were less than 10 examples in private collections.

The stamps were so rare, they were never even listed in the annual and prestigious Scott Catalogue of postage stamps, a kind of bible for U.S. stamp collectors.

With just six examples known to exist in private collections, the stamp world was rocked in the late 1980s when someone turned up with a few dozen—an apparent theft from the museum's collections.

Conspiracy theories are in abundance on the Internet over the purpose and intent of the stamps, but the 1937 federal marijuana tax stamps were never meant as schemes to entrap users, nor to further penalize those who had been arrested for pot possession who had not paid the tax—though that may well have been the intent of the 24 individual state pot tax stamps.

The National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws, NORML, maintains that “the legislative intent of [state] drug tax laws is to impose an additional penalty—tax evasion—upon drug offenders after they are arrested and criminally charged with a drug violation.”

Including marijuana in the 1971 Controlled Substances Act put an end to the federal marijuana tax stamp idea.

In 2005, the museum determined to put the excess duplicates up for auction, bringing a number of the previously rare stamps into the marketplace.

“For every single one of the revenue stamps that was issued by the Treasury Department, we had in some cases tens of thousands of copies,” Piazza says of the cache that was turned over to the Smithsonian in the 1970s. Proceeds from the auction would fund new acquisitions for the museum’s collections. Almost instantly, the stamps were put on sale at collector marketplaces.

According to the auction catalog at the time: “This sale will provide the opportunity for many collectors to acquire stamps that have a social history aspect more controversial and colorful than nearly all other areas of fiscal philately.”

Postal museum officials had hoped to yield $1.9 million from the sale of some 35,000 surplus revenue stamps for all sorts of products including silver, snuff, cheese and distilled spirits, as well as marijuana. Instead the auction raised more than $3.3 million, with a lot of interest going toward the yellow, green, blue and red marijuana stamps.

“Opening bids were $750 to $1,000 for the single stamps and over $1,000 for the multiples,” says Piazza.

“The controversial U.S. 1937 Marijuana Tax stamps—kept under lock and key for nearly 70 years—are now available to collectors for the first time,” an advertisement gushed weeks after the auction. First issue sets of four stamps went for as much as $3,250. A set of 14 stamps went for $12,000. (The items continue to sell, with one sheet of four currently listed on eBay for $3,500.)

“The ‘Marihuana Tax Act’ stamps chronicle almost 70 years of social evolution—the roaring days of Prohibition, the psychedelic Sixties and today’s medical marijuana debate,” the ad declared.

But the examples kept by the Postal Museum for historical purposes continue to draw visitors, Piazza says.

“I think there’s a steady amount of interest in them,” he says of the stamps. “People know about them and ask to see them on tours.”

For all the interest, though, they’re not all that much to look at.

“They never actually issued any purposely-designed marijuana stamps,” Piazza says. “They just took existing stamps of which they had excess quantity and overprinted them with ‘marihuana.’”

So instead of Timothy Leary, Alice B. Toklas or any Willie Nelson of the era, the stamps are printed over what Piazza calls “long forgotten” U.S. treasury secretaries. Not the first and most famous one, Alexander Hamilton, current star of Broadway and $10 bills, but various 19th-century treasury secretaries.

Levi Woodbury, appointed in 1834, is on the $1 stamp; George M. Bibb, appointed 1844, on the $5 stamp. Robert Walker, who took office in 1845, is on the $10 stamp and James Guthrie, appointed in 1853, is on the $50 stamp.

It may be more appropriate, though, that George Washington is on the $100 stamp, so rare it may not ever had originally gone into circulation. After all, one of the chief crops of the first president’s Mount Vernon estate was hemp.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)