In this series of four vignettes, Paul Gardullo, a curator with the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), tells the stories behind objects in the Smithsonian collections from the Tulsa Race Massacre on its 100th anniversary.

When NMAAHC was chartered in 2003, it held not a single artifact in its collections nor a single photograph in its archives. African American history, largely denied by public institutions—including the Smithsonian itself—is a foundational component of the nation's story. To build the museum's ground-laying collections, curators resolved to create a mandate that could not only provide evidence of the centrality of the Black narrative in America, but could also powerfully demonstrate the complex themes of violence and persecution, as well as the humanity, creativity, resistance, love, joy and resilience demonstrated by African Americans in the face of, and beyond the boundaries, of oppression.

For many of us, working on the team assembling the stories that this new museum would tell, the work represented an opportunity to meet the challenge of telling a more complete, more truthful American story. James Baldwin eloquently captured the charge when he wrote: “American History is longer, larger, more various, more beautiful and more terrible than anything anyone has ever said about it.”

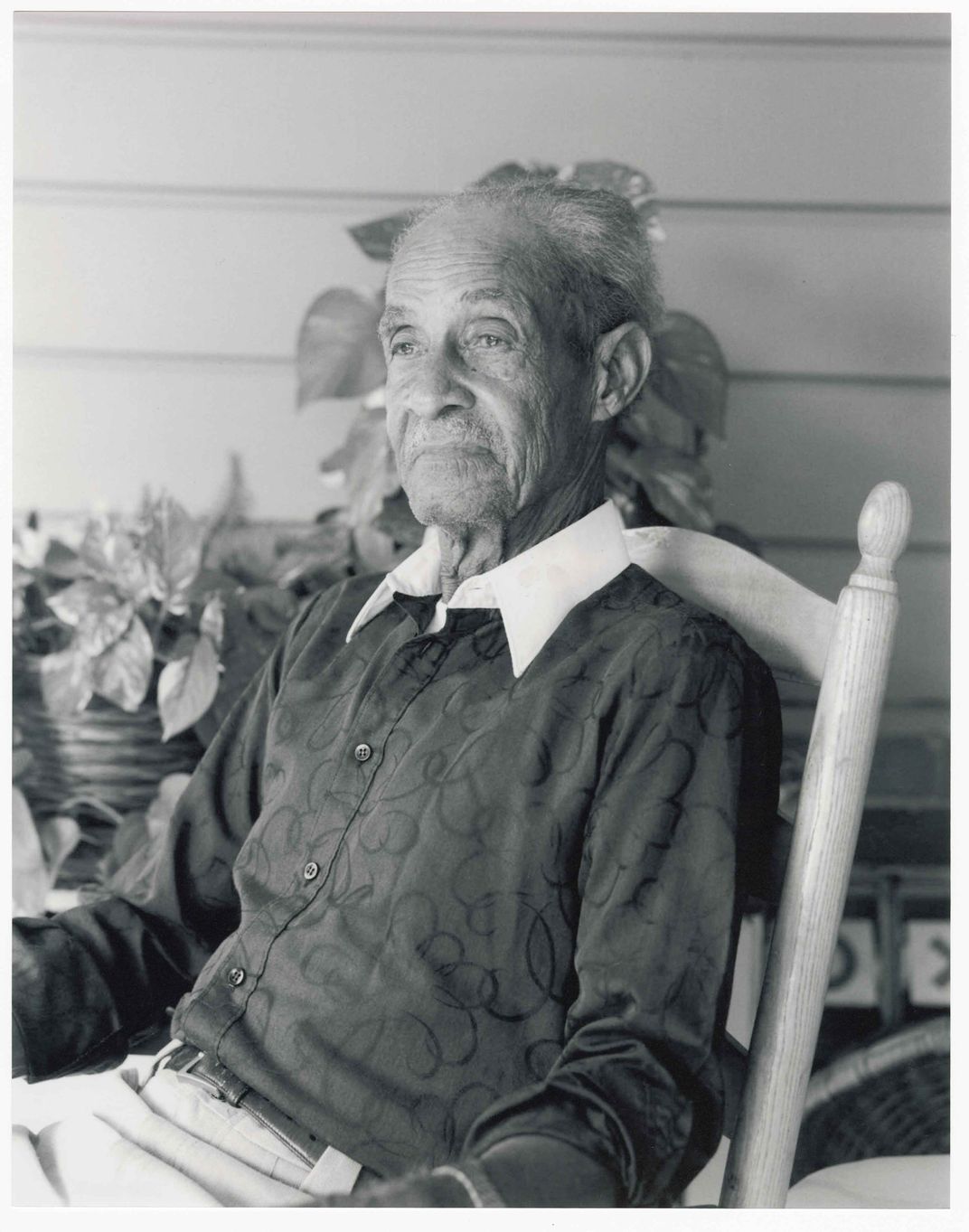

That charge has led us to embrace an expansive and transformative new vision of collecting and collections care that has forced us to rethink basic questions of museum work—provenance, curation, cataloguing, preservation and interpretation. It has also forged a reshaping of relationships with communities and individuals who entrusted us with their histories and keepsakes, small and large. For me, the epitome of that vision is nowhere better illustrated than in the museum’s work filling the silences in our nation’s memory by working with families, institutions and communities for six years collecting around the Tulsa Massacre, and most importantly by centering the testimonies of survivors and descendants like George Monroe, Anita Williams Christopher, William D. Williams, Buck Colbert (B.C.) Franklin, Olivia Hooker and dozens of others.

The museum’s Tulsa and Black Oklahoma collection now includes more than a dozen artifacts, approximately 425 photographs and some 93 archival and ephemeral documents, along with 13 films. Each represents a profound demonstration of the immense trust in the role that a national museum can provide in its practice of collecting, and its care and respect for the relationships curators and historians build with individuals, families and communities. They give voice to stories of violence and destruction often only through fragments, small objects, images and testimonies. These artifacts, along with NMAAHC’s Tulsa Race Massacre Oral History Collection—one of the largest digital compilations—illuminates the fuller lives of people who suffered tragic loss and were too often forgotten. They also demonstrate a new understanding of the purpose of memory, one that changes how we value our history and what we value from our collective past.

Coins as Metaphor

George Monroe was almost five years old on May 31, 1921, when his world was set on fire. The Monroe family lived on East Easton Street near Mount Zion Church in Greenwood, Oklahoma, the thriving African American neighborhood of segregated Tulsa. Osborne Monroe, George’s father, owned a roller-skating rink amidst an array of grocery stores, theaters, hotels, garages, service stations, funeral parlors, as well as churches, schools, hospitals and homes—all owned and operated by Tulsa’s Black citizens.

“We looked out of the front door and saw four white men with torches coming straight to our house,” Monroe would later recall. “My mother told my two sisters, brother and me to get under the bed. These guys came into the house and set the curtains on fire. As they were leaving, one stepped on my hand and I hollered. My sister, Lottie, put her hand over my mouth. Thank God she did. When we went outside, there were a lot of bullets flying, commotion and a lot of fires.”

From May 31 through June 1, white mobs murdered scores of African Americans and ransacked, razed and burned Greenwood’s homes, businesses and churches. The Monroes’ home and business were both destroyed.

Monroe recounted his story in 1999, eight decades after the community of Greenwood suffered the deadliest racial massacre in U.S. history. “I remember that as if it was yesterday.”

Greenwood was one of dozens of acts of mass racial violence that convulsed across the U.S. with increasing alacrity and systematic routineness that began during the period of Reconstruction.

A partial list conjures the expansive and dizzying geography of this array of organized white violence that continued well into the third decade of the 20th century: Memphis, Tennessee (1866), Colfax, Louisiana (1873); Clinton, Mississippi (1875); Hamburg, South Carolina (1876); Thibodaux, Louisiana (1887); Omaha, Nebraska (1891); Wilmington, North Carolina (1898); Atlanta (1906); St. Louis (1917); Washington, D.C.; Chicago; Elaine, Arkansas (all part of Red Summer, 1919); Rosewood, Florida (1923); Little Rock, Arkansas (1927).

All took place against a backdrop of systemic racial segregation, individual acts of terror, and extralegal lynching—bolstered by law—across the national landscape. Oklahoma alone suffered 99 lynchings between 1889 and 1921.

In the aftermath of the Tulsa’s 1921 massacre, when nearly all of Greenwood was burned, Black Tulsans, with assistance from a network of African American churches and eventually the National Red Cross, who were coming to the aid of the victims, began to piece together what had been shattered or stolen. Witnesses to the massacre described white mobs looting black homes and churches. The American Red Cross reported that out of 1,471 houses in Greenwood, 1,256 were burned and the rest looted. But Black Tulsans were not simply passive victims. Survivors testify time and time again that many residents of Greenwood took up arms to defend their homes and families.

Young George Monroe, like many children amidst the devastation, tried to find solace and make sense of this new world. He was one of hundreds of Greenwood’s children who were forced with their families to face the devastation born from racial violence.

For Monroe, searching for coins left behind by the looters became a survival and coping strategy in the weeks after the massacre. The coins were there in the first place largely because, despite Greenwood’s strong business and social community, a bank had never been established in the Black neighborhood of North Tulsa. To protect their hard-earned wealth in a sharply segregated world, many families kept their money at home, sometimes hidden in a piece of furniture, other times buried in the yard.

Monroe combed the ground around his neighborhood, sometimes bending low to collect charred pennies, nickels and dimes. Copper pennies, with a melting point of approximately 1,900 degrees Fahrenheit, did not disintegrate in the fires. Gathering these tangible relics—hard, resistant, able to withstand the most searing heat, would help Monroe bear witness. Monroe fashioned a roll of dimes that had been fused in the heat of the fires into a homemade necklace and he would wear it in remembrance.

The coins would become a metaphor for the resilience found within himself and in his community. George Monroe held on to them for decades. Monroe would never forget but as the years wore on and the Tulsa massacre would largely be erased from the local, state and national collective memory.

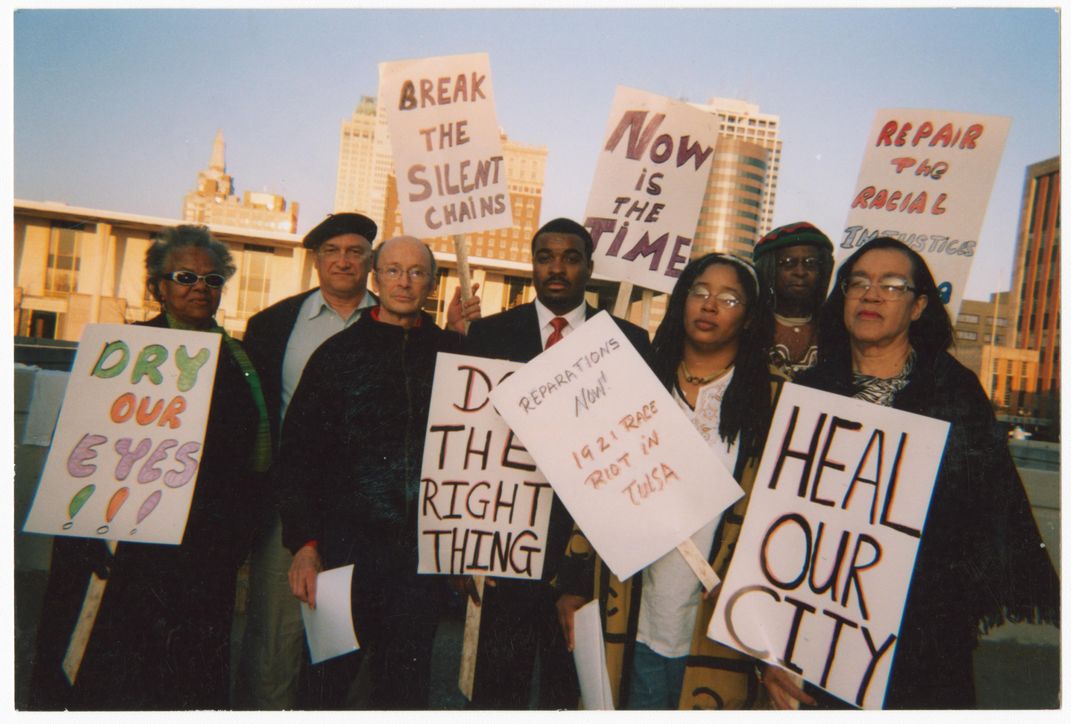

In 1997, when the State of Oklahoma convened the Tulsa Race Riot Commission, following years of advocacy by organizers, historians, activists and community groups, Monroe shared some of his coins and gave his testimony of the events of 1921. (In years since, historians have come to describe these events more accurately as a race massacre, rather than a riot)

Five of his pennies are now held in NMAAHC’s collections. They came as a donation from historian Scott Ellsworth, who served as a member of the Riot Commission and who understood the power of the pennies as some of the most powerful and tangible symbols of the massacre, stating: “I know that my old friend, the late George Monroe, would have heartily approved.”

The pennies are on display as the centerpiece of the museum’s exhibition on the topic, which details the decades-long reverberations from that harrowing event and the resilience of the Black community across time in striving for reckoning, repair and justice.

They are also tangible reminders of the sacred trust between NMAAHC and the people whose histories are represented to the world. They carry new currency as Smithsonian treasures; artifacts that need to be measured by a new calculus of truth-telling and reckoning about our country’s shared history and our shared future.

Reconstructing the Dreamland

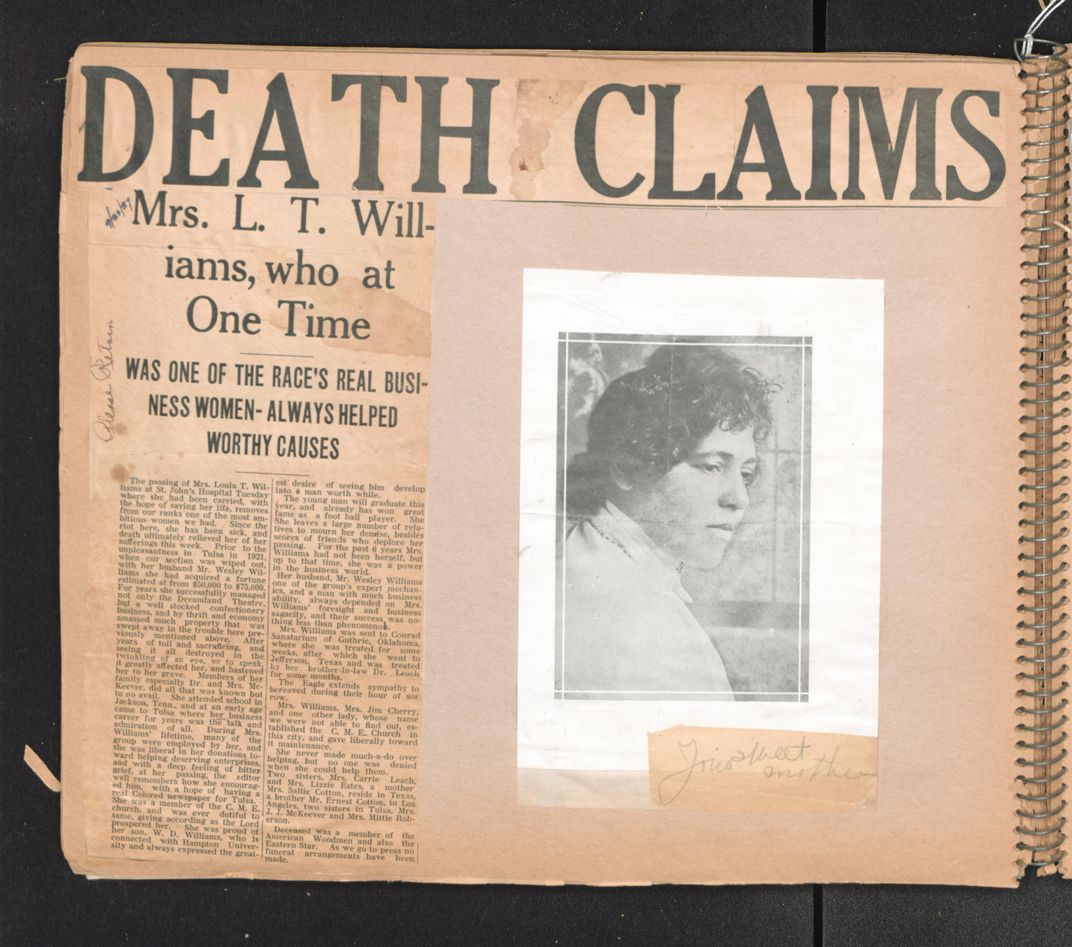

Anita Williams Christopher laid out some of her father William D. Williams’ collection of materials related to the massacre on the top of an old desk that had belonged to her grandparents, John Wesley and Loula Mae Williams, proprietors of the Dreamland Theatre, one of Greenwood’s most iconic and prosperous institutions. The aspirational qualities of Greenwood’s community of Black strivers were reflected in the name of the Williams theater itself. This success provoked resentment among white Tulsans as it did elsewhere in a society structured by white supremacy. During the massacre, the Williams’ theater was burned to the ground.

The desk dates to the period following the tragedy, Christopher told me. Within several years, the Williams’ had determinedly rebuilt their businesses. This was not an anomaly; within a year of the destruction of Greenwood, more than 80 Black-owned businesses were rebuilt. In 1925, in a marked display of courage and defiance, the National Negro Business League held its 26th annual convention in Greenwood in a triumph of the community’s resolve and resilience.

From this desk in the mid-1920s, Loula Mae Williams wrote to her son, William, while he was a student at Virginia’s Hampton Institute (he had been a teenager living at home in Tulsa in 1921) as she and her husband recouped their losses and rebuilt from the ground up with the support of the local and national Black community. “My Own Darling Boy,” she wrote. “You know not how your precious mother prays for your success. . . . I wish so much you could take your mother away from here . . . but papa tries to cheer me and say we can pull out.” In these short letters, she reveals how the massacre forever changed her health, finances and spirit.

William lovingly assembled a scrapbook that traced these years and includes telegrams along with an obituary notice for his mother after she died in an asylum in 1928, a victim of the long-term trauma of the massacre.

With the donation of the desk to the museum, Christopher urged us to be certain to not only tell a story of both resilience and loss, but also to help tell the story of her own father’s lifelong commitments to remembering Greenwood’s history and to building community. The collection bears witness to these legacies.

After his years of study in Virginia, Williams returned to Tulsa to teach history at his alma mater, Booker T. Washington High School, one of the very few buildings in Greenwood that was not burned down. Williams became the high school yearbook editor and unofficial community historian of Greenwood. He kept the memory of the massacre alive for young people long after the landscape had been cleared of its scars, teaching his students every year, doggedly recounting what happened.

This year, the city of Tulsa officially added the events of 1921 to its curriculum, yet generations of Booker T. Washington students knew the history well, having learned from W.D. Williams. He used his own curriculum materials that included postcards, pictures, scrapbooks and other ephemera. These original teaching tools now reside, alongside an assortment of other school memorabilia, in the museum’s collections. One of Williams’ students was Don Ross, who became a state representative and successfully lobbied to create the state commission to study the massacre and seek reparations. He has claimed that without Mr. Williams’ tireless documentation and advocacy for the truth, the memory of the massacre may have been lost forever.

A Long-Lost Chair

It had long been the museum’s goal to open the doors to a public truth-telling about African American history. We also wanted patrons to feel secure that the materials that people held in their homes, their basements and their attics, could be brought into the light of day and cared for, be better understood, historically valued, and when welcome, shared.

Sometimes items would come to light without warning. During a previous anniversary of the Tulsa Race Massacre, someone anonymously left a package overnight on the doorstep of the Greenwood Cultural Center, one of the chief protectors of Greenwood’s history and heritage since the 1990s. To the staff’s surprise, the package contained a heretofore unknown, handwritten account of the massacre and its aftermath.

One of the most charged issues surround possessions that were looted by white individuals and groups from Black homes, businesses and institutions. These materials survived the destruction and often remained with white families for many years. Much like the history of the massacre itself, these objects remain unspoken about, but are painful remnants of the event. Over the years, some objects were returned. A necessary process of restoration and repair, however, must address this topic despite its fraught feelings of shame or guilt.

In the collections, we keep a chair that was reportedly looted from a Black church during the massacre.

It reappeared in Tulsa in a consignment shop with an anonymous note testifying to its history. Playwright, actor and activist Vanessa Adams Harris, who produced a one-woman play on the massacre, “Big Mama Speaks,” built upon historical research conducted with survivors, rescued the chair and donated it to NMAAHC. It is a powerful and tangible symbol of what was lost and what still may be able to be reclaimed in Tulsa through an honest accounting of the past. We also hope that this object can be a portal through which to discuss memory, the topic of ownership and loss, and the complexity of what is at stake in reconciliation or practices of restorative history.

The chair also provides a window into the deep importance of Greenwood’s spiritual community. Throughout American history, independent Black churches and places of worship became the cornerstones of Black communities. As sites for schools and political meetings, as well as for religious services, they have long been engines for moral, spiritual and civic education. As long-standing symbols of community, freedom, and empowerment, for centuries they have also been targeted for acts of racial terror. That story was never truer than in Tulsa in 1921.

Greenwood represented more than just prosperous Black businesses. More than a dozen African American churches thrived in Tulsa before 1921; during the massacre, eight were defiled, burned and looted. Those left standing, such as First Baptist, which bordered a white neighborhood, became points of refuge and sustenance for survivors.

Founded in a one-room wooden building in 1909, Mt. Zion Baptist Church was testament to the flourishing Black community. An imposing new $92,000 home for the church was dedicated on April 10, 1921. During the massacre, a rumor spread among the white mob that the church was a storehouse of weapons for Black resisters. It was set on fire, but the walls of the first-floor meeting room became a temporary chapel. Twenty-one years passed before the church was rededicated on its original site.

Following the destruction, churches became galvanizing forces to help people get back on their feet and remain in Tulsa. According to survivor Olivia Hooker, her father traveled with the secretary of the YMCA, Archie Gregg, on a speaking tour of Black churches of the United States in the immediate aftermath of the massacre. “They went to Washington to the AME Zion Church. They went to Petersburg and Lynchburg and Richmond where the Black people in those towns sent missionary barrels of shoes and useful clothing and those things were being distributed out of the undestroyed part of Booker Washington High School.”

Tulsa churches remain vital to the well-being of their congregations and wider communities. In 1921, Vernon A.M.E. Church also served as a sanctuary to victims, sheltering people in its basement as the fires burned away the floors above ground. Today, rebuilt, it serves as the heart of Tulsa’s reparations and justice movement. In the words of Reverend Robert Turner, current pastor at Vernon: “I believe there is no expiration date on morality. And if it was wrong in 1921 and has not been repaired for by today, then we ought to do something about it.”

Testimony as Literature

Born in 1879, the civil rights lawyer Buck Colbert (B.C.) Franklin moved from the all-Black Oklahoma town of Rentiesville to Tulsa in 1921. He set up his law practice in Greenwood. His wife and children (including 6-year-old John Hope Franklin, the preeminent historian and founding chair of NMAAHC’s Scholarly Advisory Committee) planned to join him at the end of May.

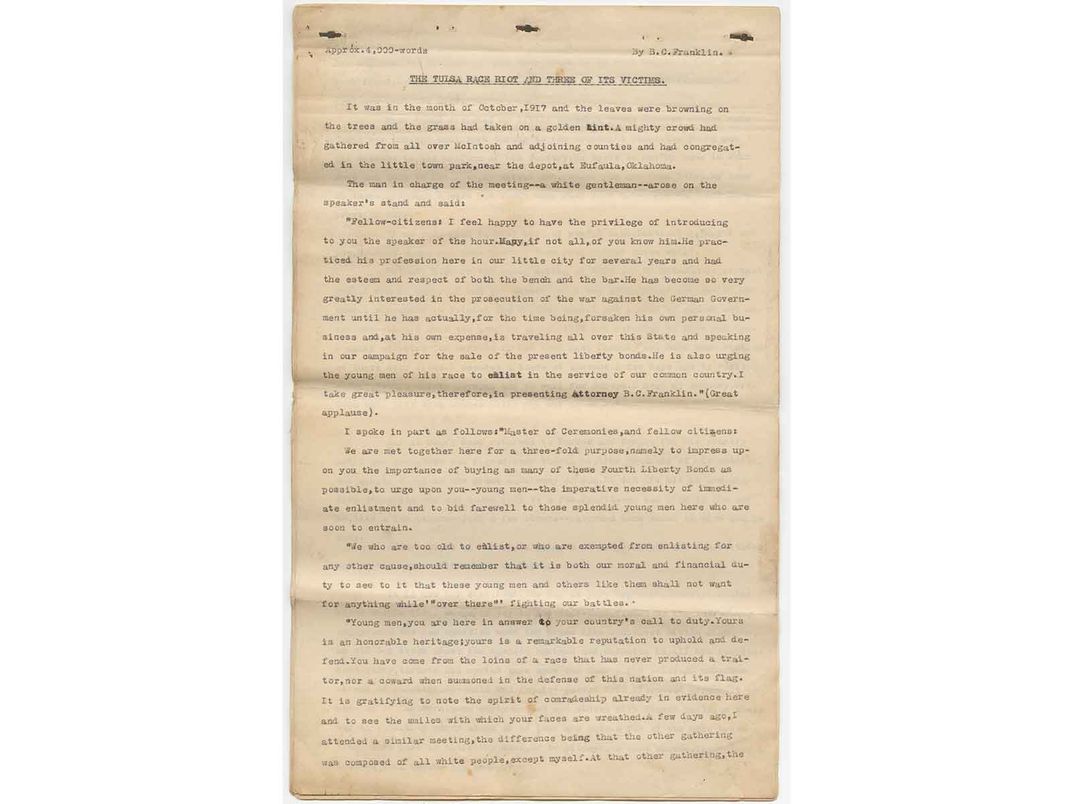

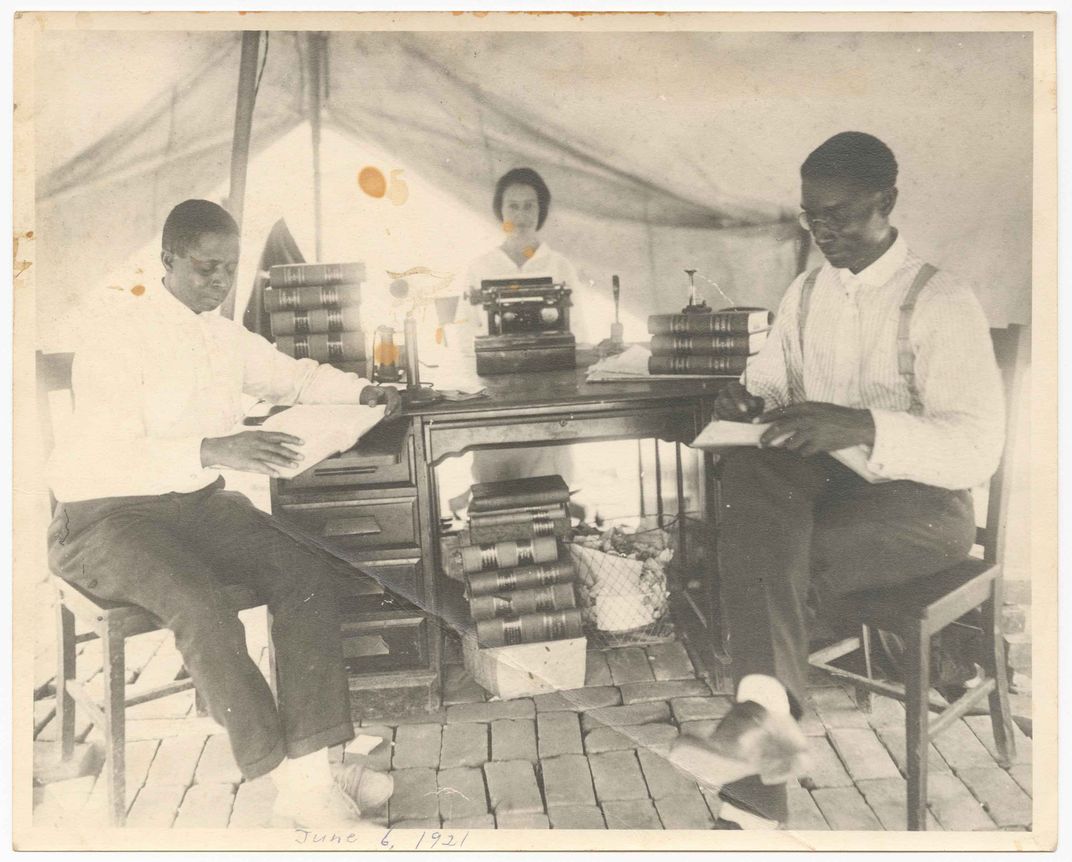

The massacre delayed the family’s arrival in Tulsa for four years. After his office was destroyed, Franklin practiced with his law partner I.H. Spears from a Red Cross tent erected in the midst of the still-smoldering ruins. One of his most instrumental successes was challenging a new law that would have prevented residents of Greenwood from rebuilding their property destroyed by the fire. “While the ashes were still hot from the holocaust,” Franklin wrote, “. . . we instituted dozens of lawsuits against certain fire insurance companies . . . but . . . no recovery was possible.”

Franklin and Spears rescued Greenwood’s future as a Black community by successfully arguing that residents should be able to rebuild with whatever materials they had on hand. While Franklin’s legal legacy is secured and recorded within the dozens of suits and briefs filed on behalf of his clients, his talent in recording this pivotal event in American history has been unrecognized. His unpublished manuscript, written in 1931, was uncovered only in 2015, and is now held in the museum’s collections. Merely ten pages long, “The Tulsa Race Riot and Three of Its Victims” is a profound document.

Objects and oral histories have pushed the city and the nation toward a more truthful understanding of the past. Franklin’s manuscript is a foundational part of that process of factually bearing witness, but it is also more than just evidentiary; it is a meditation and evocation that performs at the intersection of memory, history and literature.

Franklin’s memoir is structured around three moments, detailing encounters with an African American veteran, surnamed Ross. It begins in 1918, soon after World War I, when Ross is angry because of his treatment despite his military service; it proceeds to an account of Ross defending home and family in 1921 during the massacre, and ends ten years later with his life in tatters and his mind in ruins. By choosing to center on a Black veteran, Franklin crafts a deep analysis on patriotism, disillusionment and ultimately trauma, threading a connection of the story of the Tulsa massacre to the nation’s broader story of the betrayal of those willing to sacrifice all for a nation that refuses to respect them.

Depicting encounters with Ross that traverse nearly 15 years, Franklin breaks free of some of the conventions that frame the typical survivor’s testimony, which rely mostly on recounting the events directly surrounding the massacre. Yet his eyewitness perspective, too, is filled with rich detail that describes the defense of Greenwood by its Black citizens, debates about violence and how best to make change. The eyewitness account of “planes circling in mid-air” dropping incendiary devices to burn Greenwood to its roots is a searing indictment of the white mob and its cruelty.

Franklin provides a masterful account of how the massacre crystallizes core elements of the Black experience in America and how that experience can be embodied in a single life on a single day: “During that bloody day, I lived a thousand years in the spirit at least,” Franklin recounts.

I lived the whole experiences of the Race; the experiences of royal ancestry beyond the sea; experiences of the slave ships on their first voyage to America with their human cargo; experiences of American slavery and its concomitant evils; experiences of loyalty and devotion of the Race to this nation and its flag in war and in peace; and I thought of Ross back yonder, out yonder, in his last stand, no doubt, for the protection of home and fire side and of old Mother Ross left homeless in the even-tide of her life. I thought of the place the preachers call hell and wondered seriously if there was such a mystical place—it appeared, in this surrounding—that the only hell was the hell on this earth, such as the Race was then passing through.

In his coda, Franklin combines the danger of both racial violence and the effects of choosing to forget its victims, writing plaintively of Ross, his wife and mother:

How the years have flown and how changed and changing is the whole face of this nation. It is now August 22nd, 1931 as this is being written. A little more than ten years have passed under the bridge of time since the great holocaust here. Young Ross, the veteran of the world war, survived the great catastrophe, but lost both his mind and eye sights in the fires that destroyed his home. With a burned and scared face and a mindless mind, he sits today in the asylum of this State and stares blankly into space. At the corner of North Greenwood and East Easton, sits Mother Ross with her tin cup in hand, begging alms of the passers-by. They are nearly all new comers and have no knowledge of her tragic past, hence they pay her little attention. Young Mrs. Ross is working and doing the best she can to carry on in these times of depression. She divides her visits between her mother-in-law and her husband at the asylum. Of course, he has not the slightest recollection of her or of his mother. All yesteryears are only blank pieces of paper to him. He cannot remember one thing in the living, breathing, throbbing present.

In Franklin’s haunting description of the “living breathing throbbing present” we can see ourselves in 2021 akin to those “passers-by” in 1931. We might be like the newcomers who have no knowledge or little attention to give to the past and how it is continuing to shape our lives and world around us.

In collecting Tulsa and in telling this story, the museum’s job is to help us learn that we must not be passers-by. That in remembering lies responsibility and re-adjusting our values. That the objects we collect contain histories with a chance to change us. It is in our process of collecting with an effort to fill the silences that our institutions can become more than shrines full of static artifacts and sheaths of paper in a nation’s attic but places with the potential to be genuinely transformative and a force for truth telling, for healing, for reckoning and for renewal. Places where justice and reconciliation are paired in a process as natural as living and breathing.

Re-claiming and Re-valuing History

To mark the centennial anniversary of the Tulsa massacre, NMAAHC has created the Tulsa Collections Portal offering greater access to the museum’s objects, documents, period film and dozens of hours of survivor’s memories.

These resonate not only for Tulsa, where an interracial movement for education, justice, reparations and reconciliation continues 100 years later, but for many communities across the nation where similar histories continue to shape our present, as we make imperative the need to uphold the dignity, full freedom and equality of Black lives.

The National Museum of African American History is honoring the Tulsa Centennial with these online programs: “Historically Speaking: I Am Somebody—An Evening with Rev. Jesse Jackson and David Masciotra,” Monday, May 24, 7 p.m.—8 p.m. and “Historically Speaking: In Remembrance of Greenwood,” Wednesday, June 2, 7 p.m.—8:30 p.m. when the museum and Smithsonian magazine join forces in a virtual program to commemorate the 100th Anniversary of the Tulsa Race Massacre. A panel discussion explores the development of Tulsa’s Greenwood District, the events that led to its Black residents being the target of racially motivated violence, and the community’s resilience and regrowth. Panelists include Lisa Cook of Michigan State University, Victor Luckerson, Tulsa resident and a contributor to Smithsonian magazine’s April 2021 cover package devoted to the massacre, and Paul Gardullo, historian and curator of NMAAHC’s current exhibition on Tulsa. Michael Fletcher of ESPN's “Undefeated” moderates.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/db/ab/dbab02c2-4f0b-43ed-afb1-077b0b3f77f6/longform_mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/89/3e/893eac83-d103-4c3a-a8a7-8ccc37be4263/longform_desktop2.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Paul_Gardullo_20190711_0010.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Paul_Gardullo_20190711_0010.jpg)