Relax Like You Are in 12th-Century China and Take in These Lush Landscape Paintings

When the Confucian elite got stressed, they’d stare at nature paintings to recharge and renew their souls

In a late 12th-century Chinese scroll painting entitled "Wind and Snow in the Fir Pines," famed landscape artist Li Shan depicts a lone scholar warming himself by a crackling fire. Outside, craggy mountains loom in the distance; a grove of snow-laden pine trees tremble amid a gust of icy wind.

This transportive scene is one of many serene works highlighted in an ongoing exhibition, "Style in Chinese Landscape Painting: The Song Legacy," at the Freer Gallery of Art. Featuring 30 paintings and two objects, the display draws from the museum’s permanent collections to examine stylistic traditions in natural art that evolved around the Five Dynasties (907–960/979) and the Song Dynasty (960-1279).

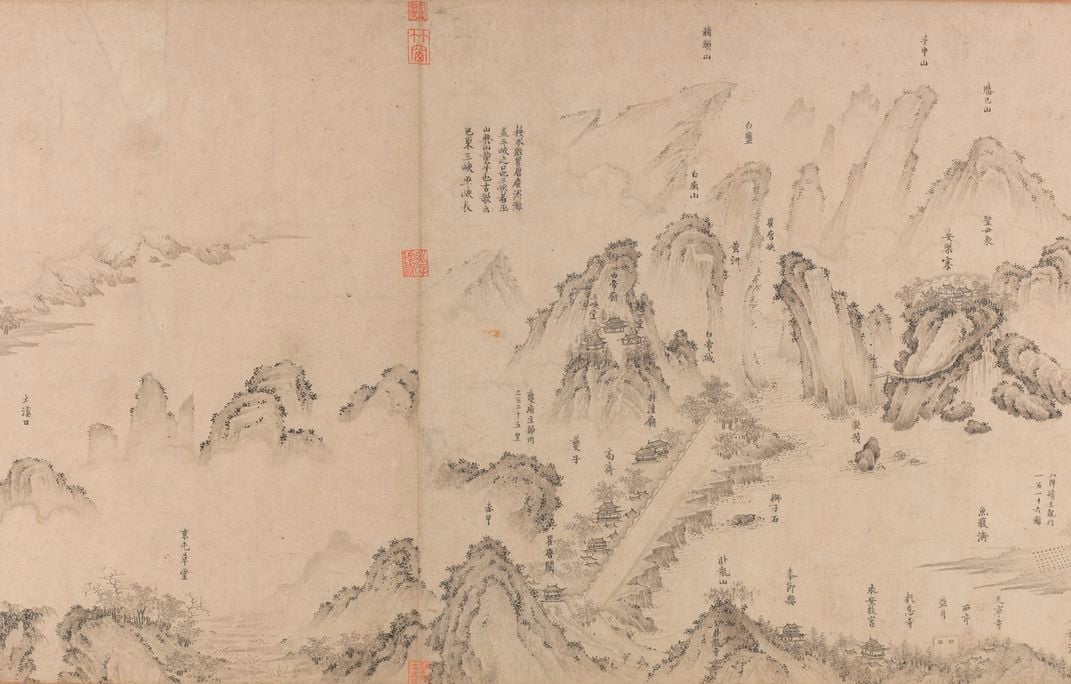

A time of war and political turmoil, the Five Dynasties ushered in the Song, an artistically fertile era in which many artists were employed to provide the imperial court with palace and temple murals, as well as portable scrolls. Landscape painting had existed in China since the third century; however, Song works particularly celebrated the beauty of the outdoors, and depicted the country’s dense forests, rushing rivers and sky-high peaks and gorges. These paintings eventually became focal points of artistic study, prompting artists to develop variations in composition, ink usage and textured lines and layers. Even though few original works from the Song have survived—the exhibition displays just seven directly from this period, although it shows Song-inspired images from the Yuan, Ming and Quing dynasties—individuals continued to emulate their approaches and techniques well into later generations.

Why did landscape gradually morph from a backround subject into a central obsession? In China's Confucian civilization, says Stephen Allee, a curator for Chinese painting and calligraphy, elite men "had an obligation to society—to teach or work in government; to make sure that others were treated right. But the government corrupts. You're no longer thinking about the Tao, the great organizing principal of the universe. You're thinking about wealth and power. You no longer have time to go to the mountains to refresh yourself."

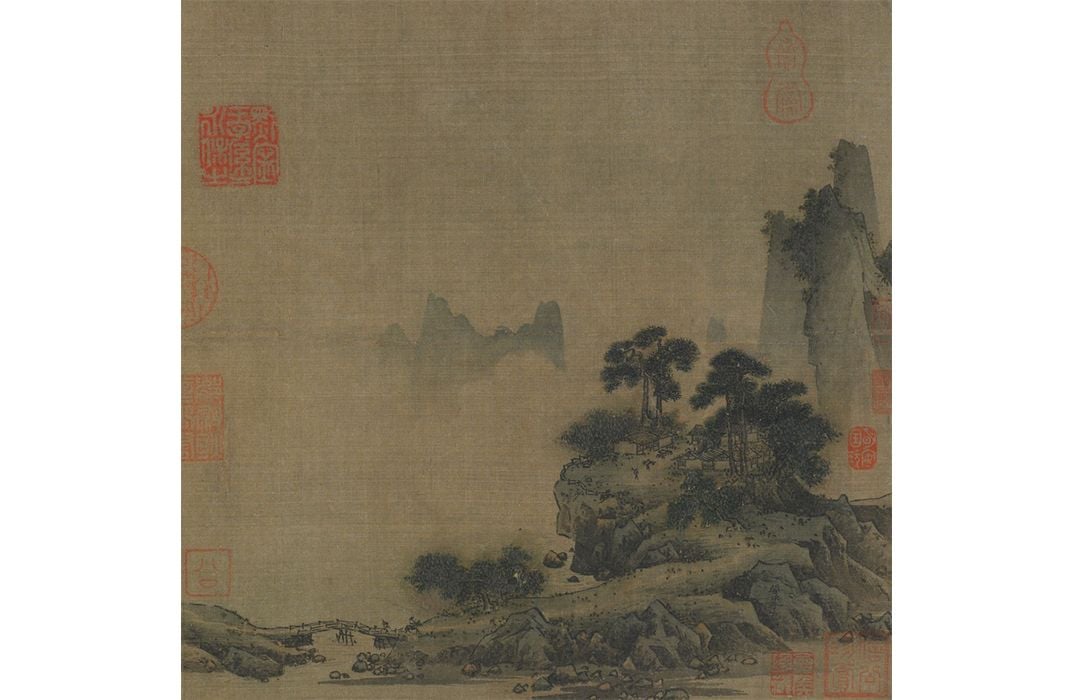

In lieu of a literal return to nature, court figures would instead purchase landscape paintings and hang them on their walls. When they felt their souls growing jaded and heavy from quotidian concerns, they'd gaze at the lush scenes and transfer themselves into the place of their inhabitants—ink-brush silhouettes holding fishing rods, gathering plum blossoms and sipping a refreshing beverage in a rustic tavern.

But the paintings' themes alone weren't what made them so transformative: new ink and brush techniques played a large part, instilling palpable sentiments and ambiance into what might have otherwise been static images.

Take into consideration "Wind and Snow in the Fir Pines." Created during China’s later Jin dynasty (1115–1234), its approach toward natural form copies the Northern Song dynasty landscape painter Li Cheng (919–967) and his subsequent imitator, Guo Xi (circa 1001–1090), who both employed billowy ink washes and spiky, energetic brushwork. Soft-lined mountains disappear into clouds, and sharply delineated trees, painted with the tip of the brush, loom in the forefront. The scene crackles with cold; it lacks human activity, but it teems with human emotion.

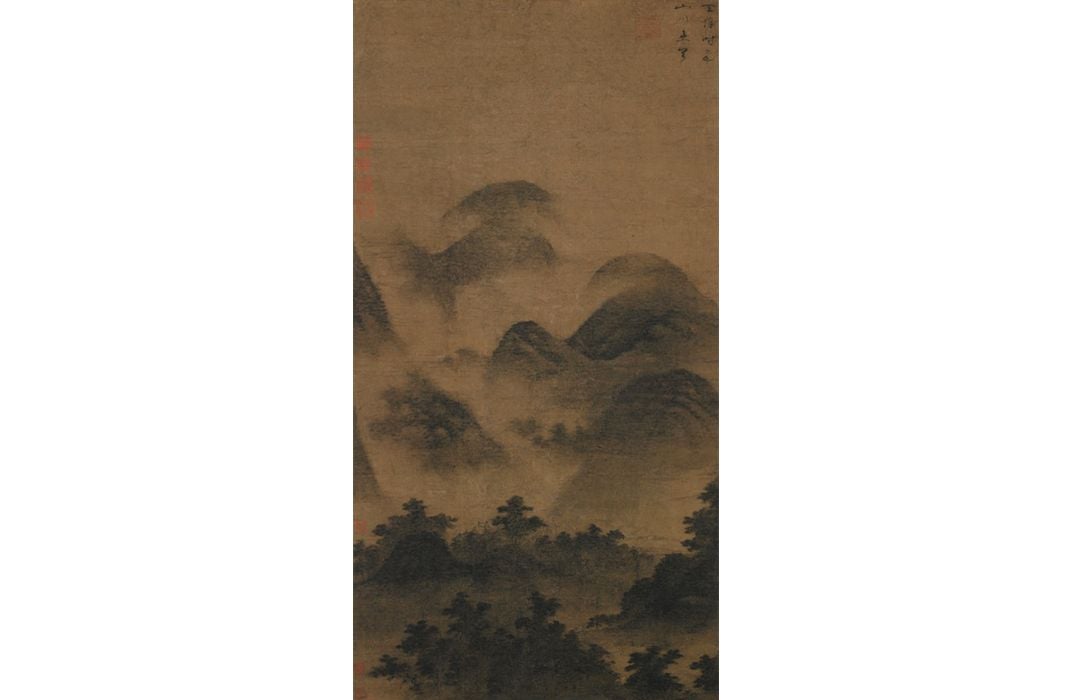

The exhibition’s other styles also imbue natural scenes with visceral moods. One example is a grouping of Mi Family paintings, associated with Song Dynasty father-and-son artists Mi Fu (1052–1107) and Mi Youren (1075–1151). Strips of fog—formed by swaths of untouched paper or silk—bathe vertiginous landforms; clumps of vegetation spring from horizontal ink dots, layered over each other until they form a sultry, textured depth. There are no straight lines; everything is washed in a foggy damp. “It’s all to evoke a misty, moist summertime in the southern part of China—heavily humid,” says Allee.

Other landscapes range from ornate and stylized to rough-hewn, rocky compositions brimming with physicality. On one side of the spectrum, the blue-and-green style features gold ink and pigments mixed from crushed azurite and malachite. Developed under the Tang Dynasty (618-907) and revived by Song rulers, this genteel style was favored by the imperial court. Meanwhile, the axe-cut brush strokes in Fan Kuan–Li Tang Style—perfected by pioneering Song dynasty artist Li Tang (1050-1130)—create powerful, long lines at an oblique angle, breathing a weight-filled texture into rocks and rivers alike.

Throughout the exhibition, styles often blur and blend into each other. Subject matters dart from river to woods to mountain range and back again. But the landscape paintings all have one characteristic in common, according to Allee, aside from sharing techniques rooted in the Song Dynasty: they allow a mental escape when a physical one isn’t possible.

“If you’re by yourself during a moment of quiet, and you’re just looking, pick a figure [in the painting]. Be that figure. It’s remarkably refreshing,” says Allee. “You lose whatever it is that’s annoying you that day—the deadlines, the pressures. They fade away for a little bit.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Fawcett-Bio.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Fawcett-Bio.jpg)